Echoes in the Prairie Wind: The Ingenious Grass Houses of the Wichita Nation

In the vast, undulating expanse of the American Great Plains, where the sky meets the earth in an endless embrace, a remarkable architectural marvel once stood as a testament to human ingenuity and adaptation: the grass house of the Wichita people. Far more than mere shelters, these dome-shaped dwellings, woven from the very fabric of the prairie, were living embodiments of a culture deeply intertwined with its environment, a sustainable and resilient response to the challenges of nomadic life and the unforgiving climate.

For centuries before European contact, the Wichita people, known as the "raccoon eyes" for the distinctive tattoos around their eyes, dominated a vast territory stretching across what is now Kansas, Oklahoma, and parts of Texas. Unlike some of their Plains neighbors who relied solely on the buffalo, the Wichita were semi-sedentary, practicing a dual economy that blended seasonal buffalo hunting with extensive agriculture. They cultivated corn, beans, and squash in fertile river valleys during the warmer months, and their unique grass houses were the perfect solution for this dual lifestyle.

"These were not temporary structures; they were homes, built with immense skill and a profound understanding of the natural world," explains Dr. Sarah Jenkins, an ethnohistorian specializing in Plains Indian cultures. "The Wichita weren’t just using materials from the land; they were building with the land itself, creating structures that were both robust and surprisingly comfortable."

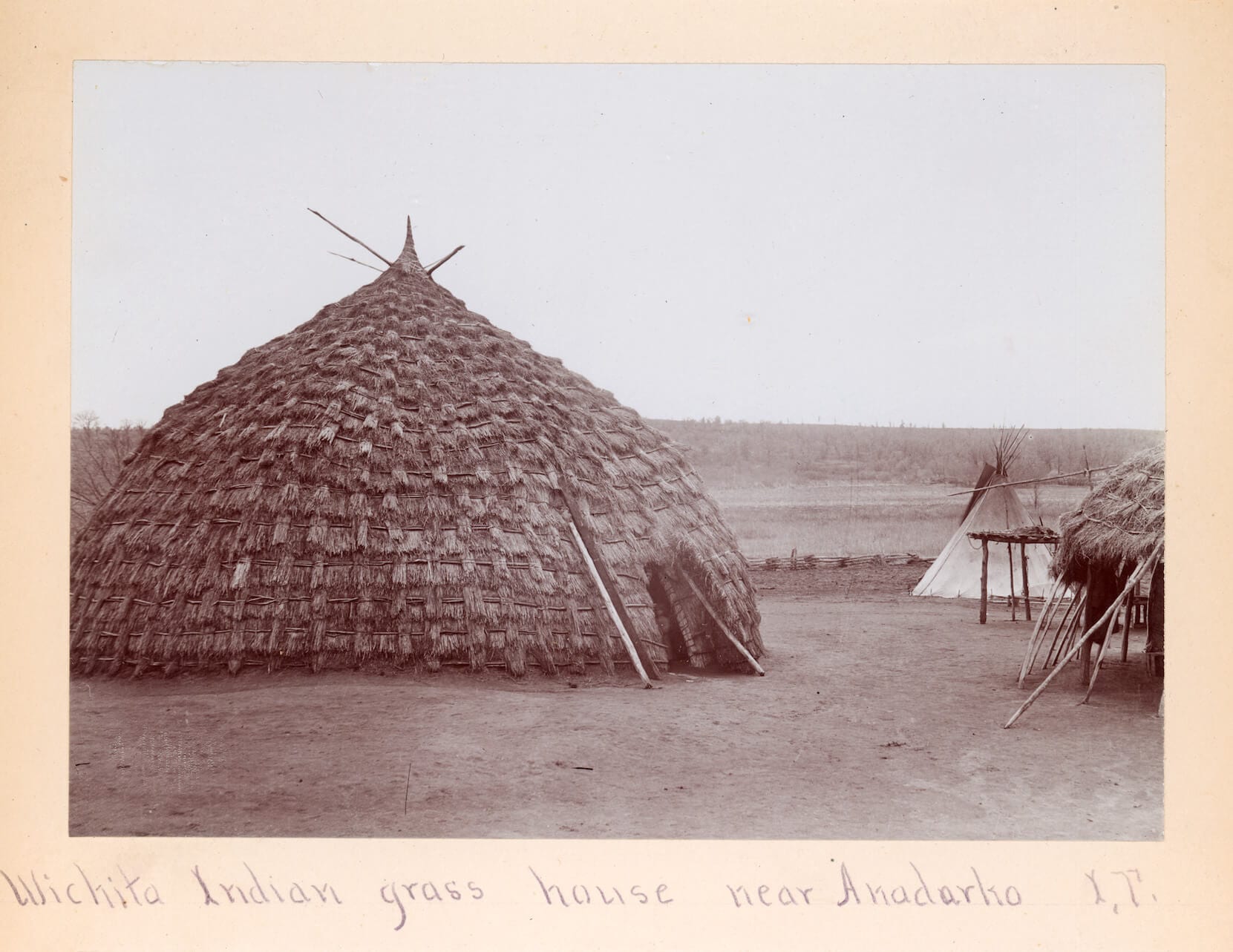

The construction of a Wichita grass house was a communal effort, a rhythmic dance of hands and expertise passed down through generations. The primary materials were the abundant tall grasses of the prairie, particularly bluestem and switchgrass, known for their strength and insulating properties. The process began with a sturdy framework of cedar or willow poles, bent and lashed together to form a large, circular dome, often reaching 30 to 50 feet in diameter and standing 15 to 20 feet high at its apex. This intricate lattice provided the skeletal integrity for the entire structure.

Once the framework was complete, the real artistry began. Bundles of carefully gathered and dried grass, often three to four feet long, were meticulously tied in overlapping layers to the pole framework, starting from the bottom and working upwards. Each layer was secured with rawhide thongs or twisted fibers, creating a remarkably dense and waterproof exterior. The bundles were laid so expertly that the grass shed water like shingles, while also providing excellent insulation against both the scorching summer sun and the biting winter winds. A large opening at the top served as a smoke hole for the central hearth, and a single low doorway, often covered with a buffalo hide, provided entry.

"Imagine the sheer labor involved, but also the incredible efficiency," says Mark Tallbear, a cultural preservationist with the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. "They could build a house of this size in a matter of days or weeks, depending on the number of people working. It was a testament to their community spirit and engineering genius. Every blade of grass, every pole, was a whisper of their ingenuity, a sustainable design that modern architects are only now beginning to appreciate."

Inside, the grass house was a world unto itself. The interior was surprisingly spacious and well-ventilated, thanks to the smoke hole and the natural breathability of the grass. A central hearth provided warmth for cooking and heating, its smoke rising through the opening above. Around the perimeter, raised platforms covered with buffalo hides served as sleeping areas and seating. Storage pits dug into the earth floor kept food and belongings cool and dry. The diffused light filtering through the grass walls created a warm, inviting glow, a stark contrast to the vast openness outside.

These dwellings were more than just shelters; they were the heart of Wichita family life. Extended families often shared a single large house, fostering a strong sense of community and shared responsibility. The houses were strategically located near rivers for water and fertile land for cultivation, forming bustling villages that hummed with activity during the planting and harvesting seasons. When the time came for the seasonal buffalo hunt, some of the lighter materials could be dismantled or the entire village could relocate, demonstrating a remarkable flexibility.

The genius of the grass house lay in its perfect harmony with the environment. All materials were locally sourced and renewable, leaving minimal ecological footprint. They were naturally insulated, requiring less energy for heating and cooling than many modern homes. Their dome shape was inherently stable, resisting the fierce prairie winds that could flatten less sturdy structures. In essence, the Wichita people had developed a "living architecture" that breathed with the land.

However, the enduring legacy of the Wichita grass houses faced an existential threat with the relentless westward expansion of European-American settlers in the 19th century. The buffalo, central to the Plains way of life, were systematically slaughtered, undermining the economic and cultural foundations of the tribes. Diseases introduced by settlers decimated populations. Treaties were signed and broken, leading to forced relocations and the imposition of reservation life.

"It was a brutal collision of worlds," notes Dr. Jenkins. "The very self-sufficiency and resourcefulness that allowed the Wichita to thrive became liabilities in the face of an encroaching industrial society that valued land ownership and settled agriculture above all else. Their traditional ways, including their unique housing, were actively suppressed as part of assimilation policies."

As the Wichita were confined to reservations, often in Oklahoma, the materials and the communal labor required for grass house construction became increasingly scarce. European building materials like lumber and canvas tents became more accessible, and traditional building knowledge began to fade under the pressure of forced acculturation. By the early 20th century, the iconic grass house had largely disappeared from the landscape, replaced by simpler, less culturally significant structures.

Today, no original Wichita grass houses remain standing. They have succumbed to the elements, their organic materials returning to the earth from which they came. Yet, their memory endures. Through oral histories, ethnographic accounts, archaeological findings, and the dedicated efforts of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes, the story of these remarkable dwellings is being preserved and retold. Reconstructions can be found at museums and cultural centers, offering a tangible glimpse into this lost architectural tradition.

These reconstructions, while valuable, are more than mere exhibits. They serve as powerful symbols of resilience, innovation, and a deep connection to the land. They remind us that complex, sustainable societies flourished on the American continent long before modern notions of "green building." The Wichita grass house stands as a silent educator, teaching us about resourcefulness, community, and the profound wisdom of living in balance with nature.

As the prairie winds continue to whisper across the Plains, they carry not just the dust of the past, but the echoes of a vibrant culture and its ingenious homes. The grass houses of the Wichita people may no longer dot the landscape, but their spirit, their lessons of sustainability and adaptation, remain an enduring part of the American story, inspiring us to look back at indigenous wisdom for solutions to the challenges of the future. The very ground beneath our feet holds the memory of these structures, a testament to the fact that true innovation often lies in understanding and respecting the world around us.