Echoes of the Plains: The Assiniboine’s Sacred Hunt for Survival

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

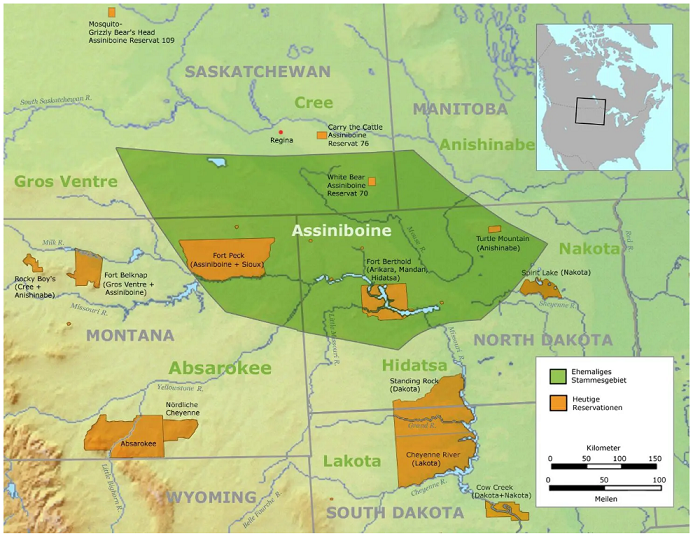

The vast, undulating plains stretch out under an impossibly wide sky, a canvas of amber grasses meeting the distant horizon. For centuries, this landscape was not merely a backdrop but a living, breathing entity, intimately intertwined with the existence of the Assiniboine people. Known also as the Nakota, these resilient inhabitants of the North American Great Plains forged a profound relationship with the land and its most majestic inhabitant: the American Bison, or buffalo. Their traditional hunting practices were not just a means of survival but a complex tapestry of skill, spirituality, community, and an unparalleled understanding of the natural world.

To understand the Assiniboine is to understand their hunt. It was the bedrock of their culture, supplying every necessity and shaping their worldview. From the thundering hooves of the buffalo came not only sustenance but shelter, tools, clothing, and the very rhythm of their nomadic lives.

The Sacred Keystone: The Buffalo

For the Assiniboine, the buffalo was far more than an animal; it was a sacred gift, a provider of all things. "The buffalo was our supermarket, our hardware store, our pharmacy, and our spiritual guide," an elder might say, encapsulating the animal’s pervasive importance. Its presence dictated their movements across the plains, following the great herds through their seasonal migrations. This nomadic existence was not aimless wandering but a strategic pursuit of life, meticulously planned around the buffalo’s cycles.

Every part of the buffalo was utilized, a testament to a profound respect for the animal and a sustainable ethos that modern societies are only now beginning to grasp. The meat provided protein, the hides became tipis, clothing, and robes, the bones were fashioned into tools and utensils, and the sinews into thread and bowstrings. Even the dung, when dried, served as fuel for fires on the treeless plains. This zero-waste philosophy was born of necessity but evolved into a spiritual principle, embodying gratitude and a deep connection to the life cycle.

The Ingenuity of the Pre-Horse Hunt: Piskun and Impoundments

Before the arrival of the horse, a creature that would revolutionize their hunting methods, the Assiniboine employed ingenious and highly collaborative techniques. The most famous of these was the "piskun" or buffalo jump. This method required intimate knowledge of the terrain and buffalo behavior. Scouts would locate a herd grazing near a cliff edge. Then, with carefully orchestrated movements, often disguised as wolves or using fire, they would subtly stampede a portion of the herd towards the precipice.

The hunt was a communal effort, involving men, women, and children. Runners, often painted and adorned to resemble predators, would drive the panicked animals forward, their collective shouts and movements guiding the herd. As the buffalo plunged over the cliff, their fall provided a massive harvest. The sheer scale of such an operation required immense coordination and bravery. It was dangerous work, but the rewards were unparalleled, providing enough meat to sustain the community through harsh winters.

Another effective pre-horse strategy was the construction of buffalo impoundments or corrals. These were elaborate traps, often funnel-shaped, built with logs, brush, and sometimes earthworks, leading into a sturdy enclosure. Hunters would carefully guide or drive a herd into the wide mouth of the funnel, gradually narrowing the path until the animals were trapped within the corral. Once inside, they could be dispatched more safely and efficiently. These impoundments, often used in winter when snow made the buffalo’s movement slower, were marvels of engineering and strategic planning, requiring significant community labor to construct and maintain.

The Horse: A Revolution on Four Legs

The introduction of the horse to the Great Plains in the 18th century fundamentally transformed Assiniboine life and hunting practices. The horse, which they called "Mishdatim" (big dog), became an extension of the hunter, dramatically increasing their mobility, speed, and efficiency. The nomadic lifestyle became even more fluid, allowing them to follow buffalo herds across greater distances and engage in thrilling, high-speed chases.

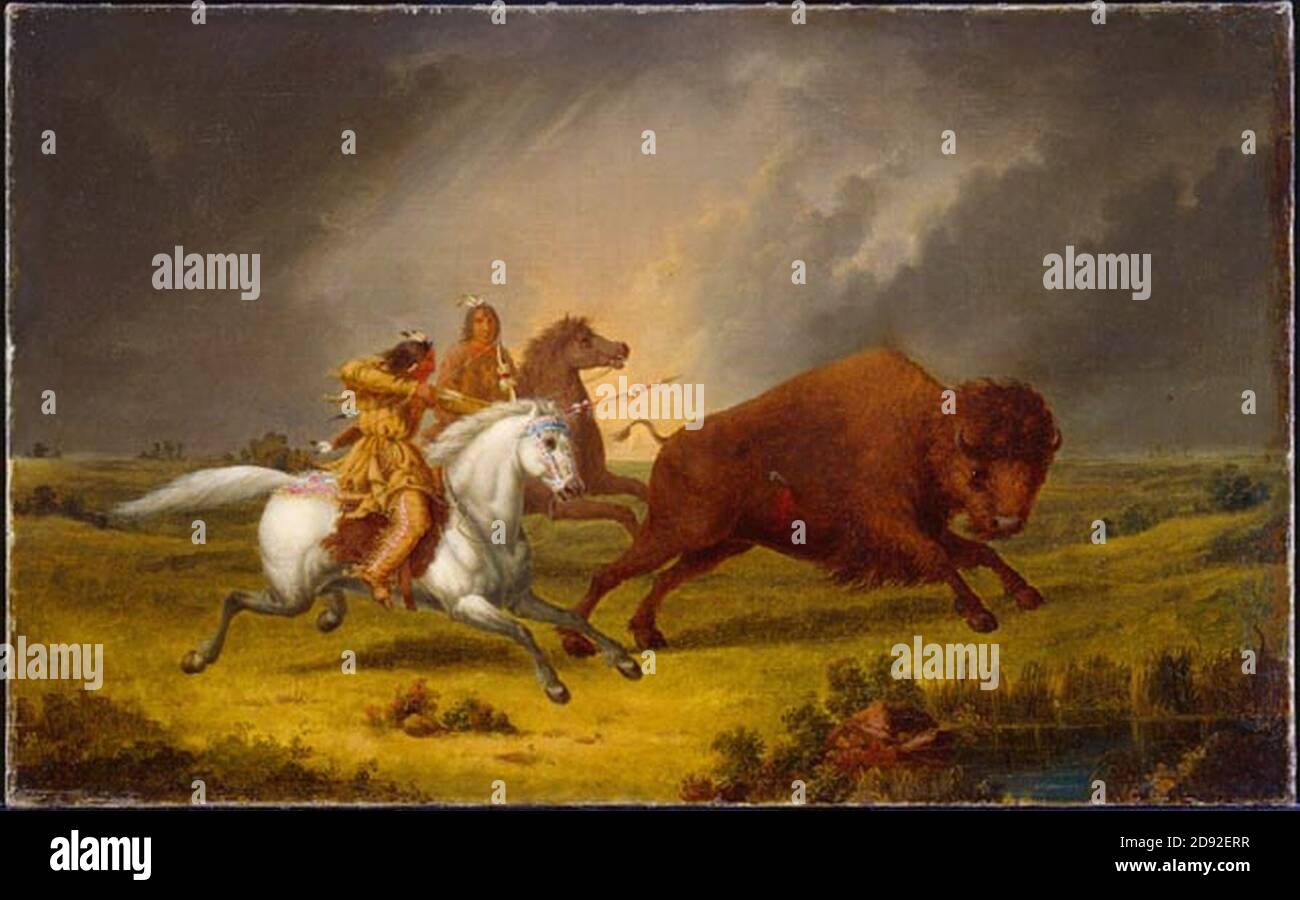

Mounted hunting was a testament to individual skill and bravery. A skilled "buffalo runner" would ride alongside the thundering herd, often on a specially trained horse capable of anticipating the buffalo’s movements. Armed with a bow and arrow or a lance, the hunter would aim for the vital organs, typically behind the shoulder, with remarkable precision. This method, while exhilarating, was incredibly dangerous. A misstep, a fall, or a charging buffalo could prove fatal. The horse-mounted hunt also contributed to the rise of a distinct warrior culture, as horsemanship and hunting prowess became highly valued attributes.

Ritual, Respect, and Preparation

The hunt was never a casual endeavor. It was steeped in ritual and respect. Before a major hunt, ceremonies would be held to honor the buffalo and seek spiritual guidance. Prayers and offerings were made to ensure a successful outcome and to show gratitude for the sacrifice of the animals. The Assiniboine believed that the buffalo willingly offered themselves for the survival of the people, provided they were treated with reverence.

Leadership for the hunt typically fell to experienced hunters or a designated "Buffalo Chief," who possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of buffalo behavior, migration patterns, and the landscape. Scouts would meticulously observe the herds, noting their size, direction of travel, and any signs of danger. Discipline was paramount during the hunt; strict rules were enforced to prevent premature charges that could spook the herd or endanger hunters. This careful preparation and spiritual connection ensured not only success but also maintained the delicate balance between humanity and nature.

From Kill to Community Sustenance: The Processing

The work did not end with the kill; in many ways, it only began. Immediately after a successful hunt, the plains would transform into a bustling scene of activity. Women, children, and elders all had vital roles in the processing. The butchering was done swiftly and efficiently, often on the spot, to prevent spoilage and protect the meat from scavengers.

The meat was then transported back to camp, where it underwent further processing. A significant portion was thinly sliced and hung to dry in the sun and wind, creating "jerky," a lightweight and long-lasting food source. The dried meat was then pounded into a fine powder and mixed with rendered buffalo fat (tallow) and often wild berries (like chokecherries or saskatoons) to create "pemmican." This highly nutritious, energy-dense food could last for years, serving as a critical reserve during lean times or long journeys. Pemmican was the ultimate survival food, providing the energy needed for their active lifestyle.

Hides were carefully scraped, stretched, and tanned, a laborious process that transformed them into pliable leather for tipis, clothing, moccasins, and robes. Bones were boiled to extract marrow, ground for bone meal, or carved into tools like hoes, scrapers, and needles. Sinews were cleaned and dried to make strong thread for sewing or powerful bowstrings. Even the bladder was used as a water container, and the stomach as a cooking vessel. This holistic utilization of every part of the buffalo underscored their profound connection to the animal and their ingenious resourcefulness.

The Social Fabric of the Hunt

The traditional hunt was a testament to communal living and collective responsibility. While individual skill was admired, the success of the hunt ultimately depended on cooperation. The bounty of the hunt was shared among the community, ensuring that everyone, especially the elderly, the sick, and the young, had enough to eat. This sharing ethos reinforced social bonds and mitigated individual hardship.

Rules and social norms governed the distribution of meat and hides, often overseen by the camp chiefs or a council. The hunt was a unifying force, bringing the entire community together in a shared purpose, strengthening their identity and connection to their ancestral lands. It was a dynamic system, evolving over centuries, adapting to environmental changes and the introduction of new technologies like the horse.

The End of an Era and Enduring Legacy

The golden age of the Assiniboine buffalo hunt, however, was tragically short-lived. The relentless westward expansion of European settlers in the 19th century, coupled with the advent of railroads and market hunting, led to the catastrophic near-extinction of the American Bison. Millions of buffalo were slaughtered for hides, tongues, or simply to deny Indigenous peoples their primary food source, effectively breaking their will and forcing them onto reservations.

This decimation of the buffalo herds was a cataclysmic event for the Assiniboine and other Plains Nations. It shattered their way of life, severed their spiritual connection to the land, and led to widespread starvation and cultural disruption. The freedom of the open plains, the thundering sound of the buffalo, and the communal rhythm of the hunt were replaced by the confines of reservations and forced assimilation policies.

Yet, the spirit of the hunt and the deep connection to the buffalo endure within the Assiniboine Nation. Today, there are ongoing efforts to revitalize bison populations and reintroduce them to tribal lands. Cultural programs and educational initiatives are ensuring that the knowledge of traditional hunting, processing, and the profound spiritual significance of the buffalo are passed down to new generations. Young Assiniboine people are learning the stories, the songs, and the skills that kept their ancestors alive for millennia.

The Assiniboine traditional hunt stands as a powerful testament to human ingenuity, spiritual reverence, and sustainable living. It speaks of a time when humanity lived in profound harmony with nature, understanding that survival was not about domination but about respect, reciprocity, and an unbreakable bond with the land and its sacred creatures. The echoes of those thundering hooves, though fainter now, still resonate across the plains, reminding us of a wisdom worth remembering.