Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English about Pueblo adobe house construction.

Earth’s Embrace: The Enduring Legacy of Pueblo Adobe Construction

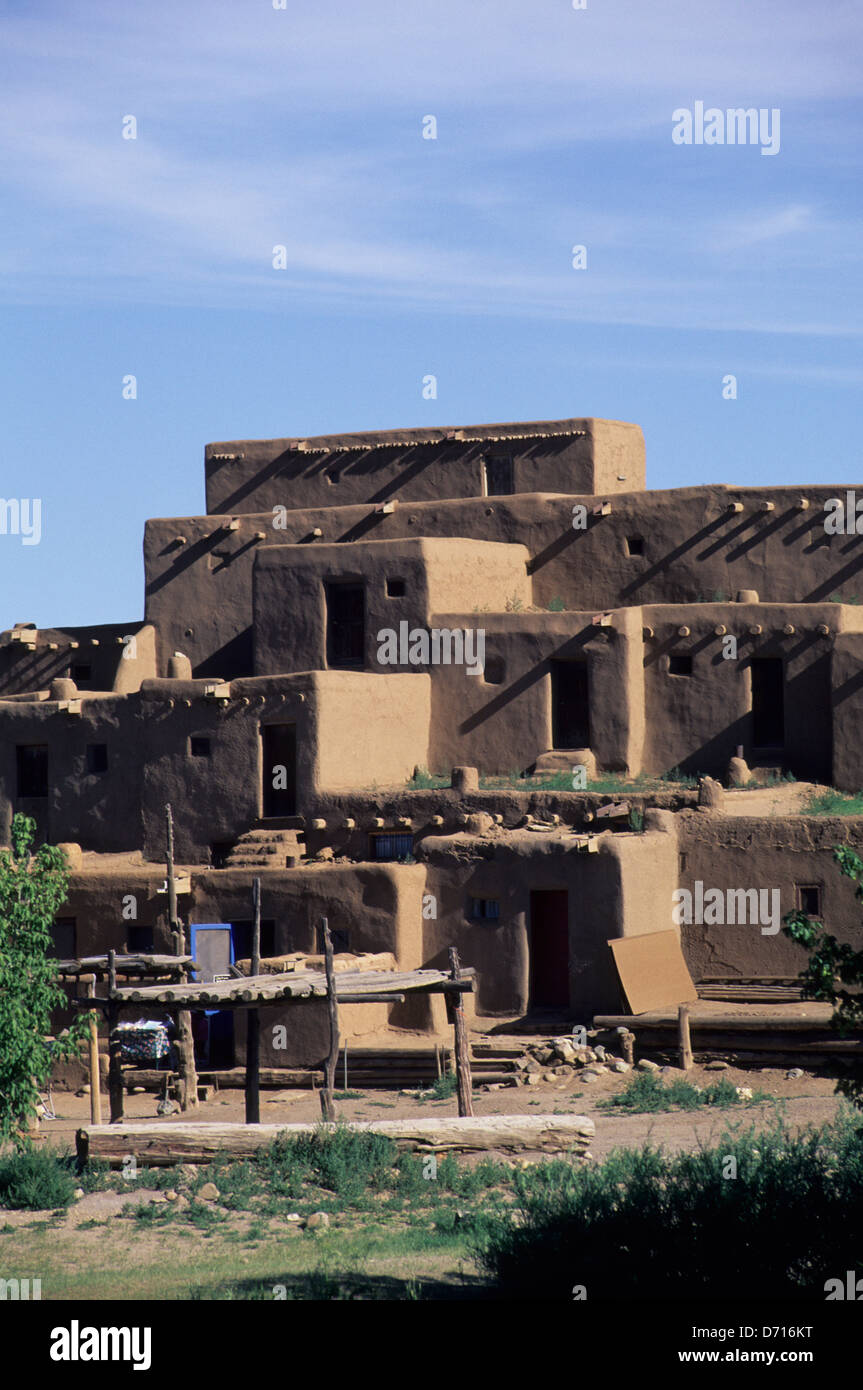

In the sun-baked landscapes of the American Southwest, where the ochre earth meets an endless sky, stands an architectural marvel that has defied millennia: the Pueblo adobe house. More than mere dwellings, these structures are living testaments to indigenous ingenuity, sustainable design, and a profound connection to the land. Built from the very soil beneath their feet, these homes represent a sophisticated understanding of passive heating and cooling, community, and an enduring respect for nature’s bounty.

The story of adobe construction in the Pueblo lands is as old as the communities themselves, stretching back thousands of years. Ancestral Puebloans, and later their descendants – the Hopi, Zuni, Taos, Acoma, and many other Pueblo nations – perfected a building technique that leveraged the most abundant resource available: earth. While early structures might have been pit houses or rudimentary brush shelters, the transition to multi-story, communal adobe dwellings marked a significant architectural evolution, culminating in the iconic terraced villages we recognize today, such as Taos Pueblo, a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America.

The Humble Material, The Profound Wisdom

At its heart, adobe is disarmingly simple: mud, sand, water, and organic material like straw or grass. Yet, it is this simplicity that belies its profound effectiveness. "It’s not just dirt," explains Elena Chavez, a cultural preservationist with ties to the Acoma Pueblo. "It’s a living material. It breathes. And it tells the story of our ancestors, who knew exactly how to work with the earth, not against it."

The process of making adobe bricks is a communal art form, often involving the entire community. Earth, ideally a clay-rich loam, is mixed with water to create a thick, pliable mud. Straw or other fibrous materials are then kneaded into the mixture. The straw acts as a binder, providing tensile strength to prevent cracking as the bricks dry, much like rebar in concrete. This blend is then pressed into wooden molds, typically rectangular, and left to dry under the intense desert sun for several weeks. The result is a rock-hard, sun-baked brick, ready for construction.

Building from the Ground Up: A Symphony of Skill and Community

The construction of a Pueblo adobe house is a deliberate, layered process, each step informed by generations of accumulated wisdom.

-

Foundations: Unlike modern homes that often require deep concrete foundations, adobe structures traditionally rest on stone foundations or compacted earth. These elevate the adobe walls above ground level, protecting them from moisture and erosion – the primary enemies of adobe.

-

Wall Construction: Once the foundations are laid, the adobe bricks are mortared together with more mud, forming thick, robust walls. These walls are typically tapered, thicker at the base for stability and gradually thinning towards the top. The sheer mass of these walls, often two to three feet thick, is a key to adobe’s thermal efficiency. They are laid course by course, allowing each layer to partially dry and settle before the next is added. This methodical pace ensures the structural integrity of the building.

-

Roofs: The Viga and Latilla System: The roofing system is another hallmark of Pueblo adobe architecture. Large, debarked log beams, known as vigas, span the width of the room, extending slightly beyond the exterior walls. These vigas are not merely structural; their exposed ends create a distinctive visual rhythm on the exterior facade. Laid perpendicular to the vigas are latillas, smaller branches or poles, often peeled and arranged in intricate patterns. On top of the latillas, a layer of brush or straw is placed, followed by several feet of compacted earth. This earth roof provides excellent insulation and contributes to the overall thermal mass of the building.

-

Openings: Doors and Windows: Traditionally, Pueblo adobe houses had very few and very small openings. Doors were often small and low, requiring occupants to stoop, a design choice rooted in both defense and climate control. Windows were also minimal, strategically placed to admit light while minimizing heat loss in winter and heat gain in summer. Early Pueblo dwellings sometimes had roof entrances, accessed by ladders, offering an additional layer of security.

-

Plastering and Maintenance: The final touch, and an ongoing one, is the application of a protective layer of mud plaster. This plaster, often mixed with fine sand or sometimes a natural pigment, is smoothed over the exterior and interior walls. It serves multiple purposes: it seals cracks, provides a smooth finish, and, critically, protects the adobe bricks from rain and erosion. This plaster needs periodic reapplication, a task that historically brought the community together for annual "re-mudding" ceremonies, reinforcing the communal bond forged in the very act of building. "The house is never truly finished," a Taos Pueblo elder once remarked. "It lives, it breathes, and it requires our care, just like our families."

Architectural Genius: Nature’s Thermostat

The genius of Pueblo adobe construction lies in its sophisticated, passive environmental control. The thick adobe walls possess incredible thermal mass – the ability to absorb, store, and slowly release heat.

- Winter Warmth: During the cold desert nights, the walls radiate the heat absorbed from the sun throughout the day, keeping the interiors warm. In the daytime, they continue to absorb solar energy, preventing the interior from overheating.

- Summer Coolness: In the scorching summer days, the walls absorb the intense heat, preventing it from penetrating the living spaces. At night, as temperatures drop, the walls release the absorbed heat to the cooler exterior, ready to absorb more heat the following day. This natural lag effect keeps the interiors remarkably cool, often 10-20 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than the outside air, without the need for mechanical air conditioning.

- Insulation: The dense, compacted earth also provides excellent insulation, further regulating indoor temperatures.

- Sound Dampening: Beyond thermal properties, adobe walls offer superior sound insulation, creating quiet, serene interiors.

This inherent sustainability makes adobe a pioneer in green building. It uses locally sourced, biodegradable materials, requires minimal embodied energy for production (primarily solar energy for drying), and offers exceptional energy efficiency throughout its lifespan.

Cultural Heartbeat: More Than Walls

Beyond its practical brilliance, adobe construction is deeply interwoven with Pueblo culture and identity. The communal nature of building fosters strong social bonds, passing down knowledge and traditions from one generation to the next. Every adobe brick, every layer of mud plaster, carries the fingerprints of ancestors and the spirit of collective effort.

"Our homes are part of us, and we are part of them," says Robert Mirabal, a Grammy-winning musician and member of Taos Pueblo. "They connect us to our ancestors, to the earth, and to our future. When we work on them, we are doing more than just building; we are continuing a sacred tradition." The terraced, multi-story design of many Pueblos also reflects a communal living philosophy, with rooms often opening onto shared plazas, fostering interaction and mutual support. The very structure embodies the community’s interdependence.

Challenges and the Enduring Legacy

Despite its many advantages, adobe construction faces challenges. Water erosion is a constant threat, necessitating regular maintenance and re-plastering. Modern building codes, often designed for conventional materials, can sometimes complicate contemporary adobe construction, though many jurisdictions now have specific codes for earthen buildings.

Yet, the wisdom of adobe endures. There’s a growing resurgence of interest in natural building techniques, and adobe is increasingly seen not as an ancient relic but as a viable, sustainable solution for modern housing. Architects and builders are reinterpreting adobe principles, incorporating elements like passive solar design, thermal mass, and natural materials into contemporary structures.

The Pueblo adobe house stands as a powerful symbol: a testament to resilience, adaptation, and a profound respect for the environment. It reminds us that the most innovative solutions often lie in the simplest, most fundamental materials. In a world grappling with climate change and resource depletion, the quiet, earthen walls of the Pueblo homes whisper lessons of sustainability, community, and the timeless art of building in harmony with the earth. They are not just houses; they are monuments to an enduring way of life, built from the very dust of ages, and destined to stand for many more.