The Enduring Tapestry: Unveiling the Historic People of Mississippi

Mississippi. The very name evokes a complex tapestry woven from triumph and tragedy, resilience and resistance. Often misunderstood, frequently caricatured, this Southern state holds a history as deep and winding as its namesake river, a history shaped profoundly by the diverse, often clashing, people who have called it home. From ancient mound builders to courageous civil rights activists, the story of Mississippi is a compelling narrative of human endurance, struggle, and the indelible mark left by generations.

The First Peoples: Guardians of the Land

Long before European sails dotted the horizon, Mississippi was a vibrant land inhabited by sophisticated Indigenous civilizations. The most prominent among them were the Choctaw, the Chickasaw, and the Natchez. These nations had complex social structures, rich spiritual traditions, and deep connections to the land, evident in the monumental earthworks they left behind, such as the Grand Village of the Natchez and the Winterville Mounds.

The Natchez, in particular, were known for their unique social hierarchy, centered around a paramount chief known as the "Great Sun," believed to be a descendant of the sun. Their resistance to French colonization in the early 18th century, culminating in the Natchez Rebellion of 1729, stands as a testament to their fierce independence and desire to preserve their way of life. While ultimately defeated, their struggle left a significant mark on the colonial landscape.

The Choctaw and Chickasaw, powerful and numerous, engaged in complex diplomacy and occasional conflict with European settlers and later the burgeoning American republic. Their forced removal in the 1830s, under the Indian Removal Act, epitomizes one of the darkest chapters in American history. The "Trail of Tears," as it became known, saw thousands of Indigenous people forcibly marched from their ancestral lands to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), a brutal act of displacement driven by the insatiable demand for cotton lands. Yet, against all odds, remnants of these nations persisted, and today, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians maintains a vibrant sovereign nation within the state, a living testament to their enduring spirit.

The Crucible of Colonization: European Powers and the Seeds of Slavery

The 18th century saw Mississippi become a contested frontier among European colonial powers. The French were the first to establish a lasting presence, founding Fort Maurepas (near present-day Ocean Springs) in 1699 and later Natchez in 1716. They were followed by the British and briefly the Spanish, each leaving their architectural, linguistic, and cultural imprints.

Crucially, it was during this colonial period that the institution of slavery was firmly established. African people were forcibly brought to Mississippi, first by the French, to labor on nascent agricultural enterprises. This was the genesis of a system that would profoundly shape the state’s demographics, economy, and social fabric for centuries to come. The labor of enslaved Africans cleared land, built infrastructure, and cultivated early crops, laying the groundwork for what would become the "Cotton Kingdom."

King Cotton and the Peculiar Institution: Wealth Built on Human Bondage

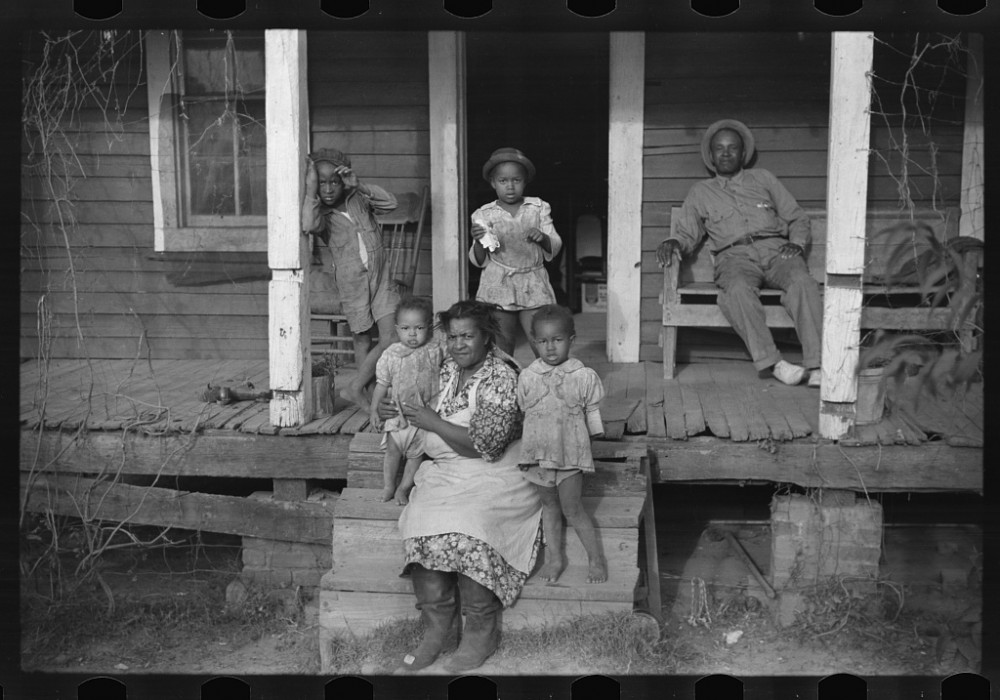

The 19th century transformed Mississippi into the heart of the Cotton Kingdom, a landscape dominated by vast plantations and the relentless, brutal labor of enslaved African Americans. The state’s fertile Delta soil proved ideal for cotton cultivation, and the invention of the cotton gin further fueled the boom. By 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, Mississippi was the wealthiest state per capita in the nation, a prosperity built almost entirely on the backs of over 436,000 enslaved people, who constituted 55% of the state’s population.

This era saw the rise of a powerful planter aristocracy, a class of white landowners who wielded immense political and economic influence. Figures like Jefferson Davis, who would become the president of the Confederacy, embodied this class. While they enjoyed lives of luxury and leisure, the vast majority of Mississippians, both Black and white, lived in far more arduous circumstances. Poor white farmers struggled to compete with the large plantations, often living in poverty on marginal lands.

For enslaved African Americans, life was a daily struggle for survival against unimaginable cruelty. They endured forced labor from sunup to sundown, constant threat of violence, separation from family, and the systematic denial of their humanity. Yet, even in the face of such oppression, they forged resilient communities, developed rich cultural traditions – including spirituals and folktales – and maintained a profound hope for freedom. As W.E.B. Du Bois eloquently put it, "The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line." In Mississippi, that line was drawn deep and stark long before the 20th century began.

War, Reconstruction, and the Betrayal of Freedom

Mississippi was a hotbed of secessionist sentiment, being the second state to secede from the Union in January 1861. The Civil War brought immense devastation, with battles like Vicksburg becoming pivotal turning points. The fall of Vicksburg in 1863 effectively split the Confederacy and granted the Union control of the Mississippi River. The war shattered the state’s economy and social structure, but it also brought the promise of emancipation.

The Reconstruction era (1865-1877) was a period of revolutionary change and profound disappointment. For a brief shining moment, African Americans exercised their newfound freedom. They voted, held public office, established schools, and sought to reunite their families. Mississippi sent Hiram Revels to the U.S. Senate in 1870, the first African American to serve in Congress. However, this progress was met with violent white supremacist backlash. Paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorized Black communities and their white allies. The "Redeemers," white Democrats committed to restoring white supremacy, gradually eroded the gains of Reconstruction through violence, intimidation, and discriminatory laws known as "Black Codes," which sought to re-establish control over Black labor and lives.

Jim Crow and the Great Migration: A New Form of Oppression

With the end of Reconstruction, Mississippi plunged into the dark era of Jim Crow. A complex web of state and local laws systematically enforced racial segregation and disenfranchisement. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses effectively stripped African Americans of their right to vote. Segregation permeated every aspect of life: schools, hospitals, transportation, public facilities – "separate but equal" was the legal fiction, but "separate and unequal" was the reality. Lynchings and other forms of racial terror were rampant, used to enforce the racial hierarchy and suppress any challenge to the status quo.

This oppressive environment led to the "Great Migration," a mass exodus of African Americans from the South to Northern and Midwestern cities in search of economic opportunity and freedom from racial violence. Millions left Mississippi, including cultural giants like writer Richard Wright, whose memoir Black Boy vividly described the suffocating racism he experienced. Yet, those who remained nurtured a rich cultural legacy, giving birth to the Delta Blues, a powerful musical form born from hardship and resilience, and later influencing rock and roll. Legendary figures like Muddy Waters, B.B. King, and Robert Johnson emerged from this crucible.

The Crucible of Change: Civil Rights in Mississippi

The mid-20th century saw Mississippi become a central battleground in the Civil Rights Movement. Its deeply entrenched system of white supremacy made it a flashpoint for activism and a target for national attention. Courageous individuals, both Black and white, challenged segregation and fought for voting rights, often at immense personal risk.

Medgar Evers, a field secretary for the NAACP, dedicated his life to organizing and advocating for civil rights in Mississippi until his assassination in 1963. Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper from Ruleville, became a powerful voice for voting rights and human dignity, famously declaring, "I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired." James Meredith’s courageous integration of the University of Mississippi in 1962, met with violent riots, highlighted the state’s fierce resistance to desegregation. The brutal murder of Emmett Till in 1955, a 14-year-old Black boy from Chicago visiting relatives in the Delta, galvanized the nation and became a catalyst for the movement.

Freedom Summer in 1964 brought hundreds of college students and civil rights workers to Mississippi to register Black voters, facing intense violence and the murder of three civil rights workers – James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. These sacrifices, alongside countless others, ultimately contributed to the passage of landmark legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, dismantling Jim Crow’s legal framework.

Mississippi Today: A Legacy of Resilience and Reinvention

Today, Mississippi remains a state grappling with its profound history, yet also one of remarkable cultural vibrancy and growing diversity. Its people continue to shape the national narrative through their contributions to literature (William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Tennessee Williams), music (the blues, gospel, and country music traditions endure), and the ongoing struggle for social justice.

The demographic landscape is evolving, with a growing Hispanic population adding new layers to the state’s cultural mosaic. While economic challenges and racial disparities persist, there are continuous efforts towards reconciliation, economic development, and building a more equitable future. Historic sites, museums, and educational initiatives are working to ensure that the complex stories of all Mississippians are told, from the Indigenous peoples to the enslaved, from the planters to the sharecroppers, and from the activists to the artists.

The story of Mississippi’s people is not a simple narrative of good versus evil, but a rich, often painful, account of human interaction, power dynamics, and the enduring quest for freedom and dignity. It is a story of resilience written in the face of immense adversity, a testament to the strength of communities, and a powerful reminder that history, in all its complexity, continues to shape the present and inform the future. The tapestry of Mississippi’s people, though scarred, remains vibrant, complex, and deeply human.