Echoes from the Sands: The Enduring Legacy of the Nauset Tribe

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

Cape Cod, Massachusetts – For many, the story of Cape Cod begins with the Pilgrims, their Mayflower skirting the shoals before landing at Plymouth. It’s a narrative often told with a focus on European arrival, overlooking the vibrant civilizations that had thrived on these shores for millennia. But beneath the layers of colonial history, etched into the very sands and salt-laced winds of this iconic peninsula, lies the profound and enduring story of the Nauset, the People of the Point.

Before the Pilgrims’ fateful arrival in 1620, the Nauset were the undisputed masters of what is now known as Outer Cape Cod. Their territory stretched from present-day Eastham south to Chatham, and inland to the freshwater ponds and forests that sustained their lives. They were a sophisticated Algonquian-speaking people, part of the broader Wampanoag Confederacy, whose intimate knowledge of their maritime environment allowed them to flourish.

“The Nauset were not simply inhabitants of this land; they were its stewards, its children,” explains Dr. Anya Sharma, a historical anthropologist specializing in Indigenous New England. “Their entire culture, their spirituality, their economy, revolved around the rhythms of the sea and the bounty it provided. They understood this ecosystem in ways we are only now beginning to grasp.”

Their villages, often semi-permanent, shifted with the seasons. Spring brought the herring run, summer the abundance of fish, shellfish, and agricultural pursuits like corn, beans, and squash. Winters saw them move inland, hunting deer and beaver, their lives a testament to sustainable living and deep ecological wisdom. Their homes, called wetus or wigwams, were marvels of natural engineering, providing warmth and shelter through harsh New England winters.

The First Encounter: A Precursor to Conflict

While the Pilgrims are often cited as the first Europeans to make significant contact, the Nauset had already endured decades of sporadic, often violent, encounters with European explorers, fishermen, and slavers. These interactions had already introduced devastating diseases, like smallpox and leptospirosis, which swept through Indigenous communities with terrifying speed, decimating populations before the Pilgrims even dropped anchor.

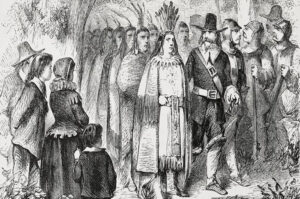

The Pilgrims’ first landfall in November 1620 was not at Plymouth, but at what is now Provincetown Harbor, within Nauset territory. Their initial foray ashore, near present-day Truro, was far from the amicable meeting often romanticized. Short on provisions, a Pilgrim scouting party, led by Myles Standish, discovered a buried cache of corn and beans. They took it. Not once, but twice. This act of theft, rather than exchange, immediately set a tone of distrust.

“Imagine a foreign ship landing on your shores, men emerging, and their first act is to raid your winter food supply,” says John Swift, a descendant of the Nauset through intermarriage, who now works with tribal preservation efforts. “It wasn’t an idyllic meeting of two worlds; it was a clash, fraught with misunderstanding and aggression from the very beginning.”

The Nauset, understandably, responded with hostility. The ensuing skirmishes, notably the "First Encounter" in Eastham, saw arrows exchanged for musket fire. It was a brief but telling harbinger of the conflicts to come. This initial aggression, coupled with the Pilgrims’ later decision to settle outside Nauset lands, at Patuxet (renamed Plymouth), which had been depopulated by disease, likely averted immediate, large-scale warfare.

An Uneasy Peace and the March of Assimilation

Despite the tense beginnings, a fragile peace eventually emerged. The Nauset, under their sachem (leader) Aspinet, were part of the broader Wampanoag Confederacy led by the formidable Massasoit Ousamequin. Massasoit, facing the existential threat of rival tribes and the devastating impact of European diseases, strategically allied with the Pilgrims. This alliance, facilitated by Tisquantum (Squanto), a Patuxet man who had been enslaved in Europe and returned to find his people gone, brought the Nauset into a complex web of diplomacy.

For several decades, the Nauset maintained a semblance of independence, though their lands gradually dwindled under the relentless pressure of colonial expansion. They became integral to the early colonial economy, trading furs and food, but the balance of power was shifting irrevocably. As more English settlers arrived, the demand for land grew insatiable.

The mid-17th century saw the implementation of "Praying Towns" – settlements where Christianized Native Americans were encouraged, or coerced, to live under strict Puritan laws, adopting English customs, language, and religion. Eastham, the heart of Nauset territory, became one such hub. For many Nauset, embracing Christianity and English ways was a survival strategy, a desperate attempt to retain some semblance of community and land in a rapidly changing world.

“The Praying Towns were a double-edged sword,” explains Dr. Sharma. “They offered a measure of protection from direct colonial violence and land seizure, but at the cost of profound cultural disruption. Traditional governance, spiritual practices, and language were systematically suppressed.”

King Philip’s War and the Fading Footprints

The true crucible for the Nauset, and indeed for all Indigenous peoples in Southern New England, was King Philip’s War (1675-1678). This devastating conflict, led by Metacom (known to the English as King Philip), Massasoit’s son, was a desperate last stand against English encroachment. While many Wampanoag and other tribes joined Metacom, the Nauset, by this point largely Christianized and strategically positioned, largely remained neutral or even sided with the English, albeit under duress.

This neutrality, however, did not spare them from suffering. Their lands continued to be diminished, their communities fragmented. The war fundamentally altered the demographic and political landscape of New England, cementing English dominance. After the war, the Nauset, like many other Indigenous groups, seemed to fade from official historical records, their distinct identity obscured by intermarriage, forced assimilation, and the relentless march of colonial expansion.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, the Nauset were often categorized by colonial authorities simply as "Indians" or "Natives," their unique tribal identity erased from public discourse. Many married into African American or European families, their descendants blending into the broader population, yet often retaining a quiet awareness of their Indigenous heritage. The Nauset language, a dialect of Massachusett, slowly faded from daily use, becoming largely dormant by the early 19th century.

Reclaiming the Narrative: The Resurgence of Identity

For generations, the Nauset story was relegated to the margins, often reduced to a footnote in the Pilgrim narrative. But the sands of Cape Cod whisper their stories, and in recent decades, there has been a powerful resurgence of interest and activism among descendants seeking to reclaim their heritage.

“Our ancestors didn’t vanish,” states Sarah Littlefield, a community organizer whose family has deep roots on the Cape. “They adapted, they survived, they persisted. The silence in the history books doesn’t mean we weren’t here. It just means our story wasn’t being told.”

Today, while there is no federally recognized Nauset tribe, numerous individuals and families on Cape Cod and beyond proudly claim Nauset ancestry. Efforts are underway to reconstruct the language, revive traditional ceremonies, and educate the public about the true history of the region. Community gatherings, historical research, and land acknowledgment initiatives are all part of this vital work.

The legacy of the Nauset is not one of disappearance, but of profound resilience. Their story challenges the simplistic narratives of early American history, reminding us that the land was never empty, and its original inhabitants possessed a rich, complex civilization that deserves to be fully acknowledged and celebrated.

From the shell middens unearthed by archaeologists to the oral histories passed down through generations, the Nauset continue to speak. Their presence is felt in the names of the land they once stewarded – Nauset Beach, Nauset Light – and in the enduring spirit of the people who call Cape Cod home. As the tides ebb and flow on the Outer Cape, they carry not just the whisper of the wind, but the powerful, enduring echoes of the Nauset, the People of the Point, who are still here.