The Reluctant Revolutionaries: How the Continental Congress Forged a Nation

Philadelphia, PA – In the annals of American history, few institutions are as pivotal, yet often as overlooked in their complexity, as the Continental Congress. It was not a grand, pre-ordained government but a desperate, evolving assembly of delegates, thrust into the crucible of revolution. From a body convened to air grievances against a tyrannical empire, it transformed, imperfectly and painfully, into the de facto government of a nascent nation, navigating war, diplomacy, and the treacherous path of self-governance. Its journey from 1774 to 1789 encapsulates the very birth pangs of the United States.

The Genesis of Resistance: The First Continental Congress (1774)

The year is 1774. Tensions between Great Britain and its American colonies have reached a fever pitch. Boston, in particular, has been singled out for punishment after the infamous Tea Party, with Parliament passing a series of punitive measures dubbed the "Intolerable Acts." These acts closed Boston Harbor, curtailed self-governance in Massachusetts, and mandated the quartering of British troops. The other colonies, seeing this as a direct threat to their own liberties, realized that a united response was imperative.

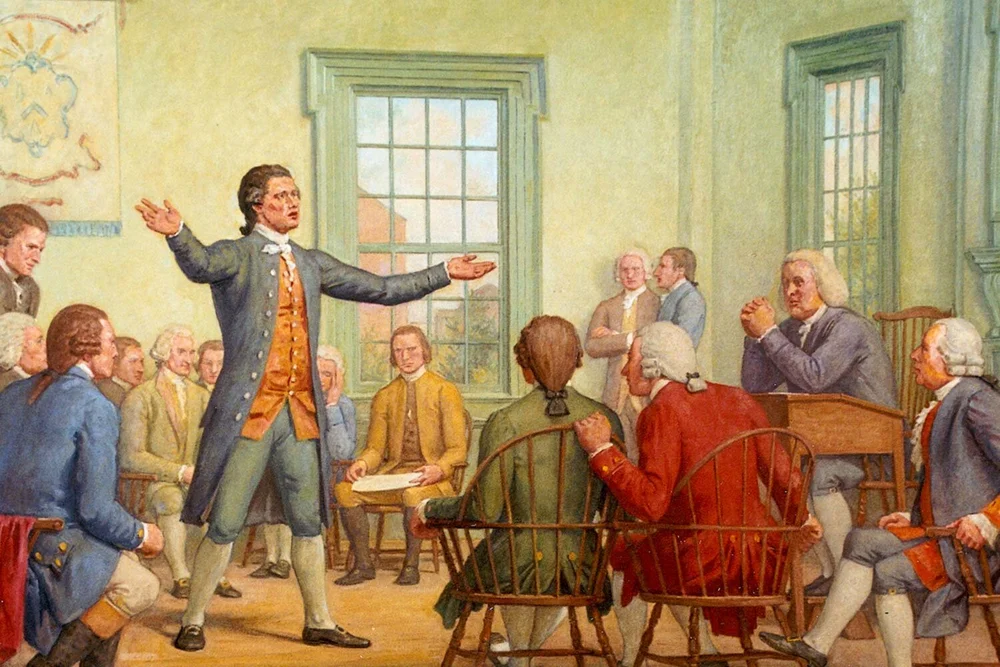

On September 5, 1774, delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies (Georgia, heavily reliant on British military protection against Native American tribes, initially abstained) convened at Carpenter’s Hall in Philadelphia. This was the First Continental Congress. It was an extraordinary gathering of some of the brightest minds and most passionate patriots of the era: George Washington, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee from Virginia; John and Samuel Adams from Massachusetts; John Jay from New York; and John Dickinson from Pennsylvania, among others.

The atmosphere was charged with a mix of fear, indignation, and an urgent sense of shared destiny. "The distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more," declared Patrick Henry. "I am not a Virginian, but an American." This sentiment, radical for its time, underscored the emerging sense of a unified colonial identity.

Their primary goal was not independence, but reconciliation – on their terms. They sought to articulate colonial grievances, assert their rights as Englishmen, and pressure Parliament to repeal the oppressive acts. After weeks of intense debate, the Congress adopted the Suffolk Resolves, declaring the Intolerable Acts unconstitutional, and, crucially, the Articles of Association. This document established a comprehensive economic boycott of British goods, to be enforced by local committees. It was a powerful assertion of economic leverage, demonstrating a newfound unity and resolve that London gravely underestimated. Before adjourning in late October, the delegates agreed to reconvene in May 1775 if their grievances remained unaddressed. They were.

From Petition to Powder Keg: The Second Continental Congress Convenes (1775)

By the time the Second Continental Congress assembled at the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall) on May 10, 1775, the landscape had irrevocably changed. Just weeks earlier, on April 19, the "shot heard ’round the world" had been fired at Lexington and Concord. Blood had been shed, and a full-scale armed conflict had erupted. The war for independence had begun, even if many delegates were still hesitant to admit it.

This Congress faced an immediate and daunting task: to manage a war that had no formal declaration, no standing army, and no established government to direct it. It quickly became a de facto national government. Its first critical act was to establish the Continental Army. On June 15, 1775, a unanimous vote appointed George Washington, the respected Virginian planter and veteran of the French and Indian War, as its Commander-in-Chief. It was a shrewd political move, uniting the northern and southern colonies behind a single, formidable leader.

Despite the escalating hostilities, a faction within Congress, led by John Dickinson, clung to the hope of reconciliation. In July 1775, they dispatched the Olive Branch Petition to King George III, a final, earnest plea for peace and recognition of colonial rights. The King, however, dismissed it out of hand, declaring the colonies in open rebellion. This rejection extinguished any lingering hope of a peaceful resolution for many, pushing the colonies further down the path to independence.

The Irreversible Leap: Declaration of Independence (1776)

As 1776 dawned, the momentum for independence became irresistible. Thomas Paine’s fiery pamphlet, Common Sense, published in January, galvanized public opinion, framing the argument for complete separation in clear, accessible language. "The sun never shined on a cause of greater importance," Paine declared, arguing that monarchy was an absurd form of government and that America’s destiny lay in becoming a free and independent republic.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution: "Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."

The debate was fierce. Some delegates still feared the consequences of such a radical break, while others, like John Adams, passionately argued for it. A committee of five – Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston – was tasked with drafting a formal declaration. Jefferson, a masterful writer, penned the eloquent words that would define American ideals: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

On July 2, 1776, the Congress voted to adopt Lee’s resolution, formally declaring independence. Two days later, on July 4, they adopted the Declaration of Independence. It was a moment of profound courage and immense risk. As Benjamin Franklin famously quipped to John Hancock after signing, "We must, indeed, all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." The die was cast. The Continental Congress, now undeniably the government of a rebellious nation, had committed to a war for its very existence.

Governing Through Chaos: The War Years (1776-1783)

With independence declared, the Congress faced the monumental task of governing a war-torn nation with no established precedent and limited power. Its challenges were staggering:

- Funding the War: Lacking the power to tax, Congress resorted to printing vast quantities of paper money, known as Continentals. This led to rampant inflation, famously giving rise to the phrase "not worth a Continental." They also sought loans from foreign powers, particularly France.

- Supplying the Army: Providing food, clothing, arms, and ammunition to Washington’s forces was a constant logistical nightmare, often hampered by state jealousies and inadequate transportation.

- Foreign Diplomacy: Congress dispatched brilliant minds like Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay to Europe to secure alliances, loans, and recognition. Franklin’s charm and diplomatic prowess were instrumental in securing the crucial Treaty of Alliance with France in 1778, turning the tide of the war.

- Maintaining Unity: Factionalism and regional loyalties often threatened to splinter the fragile union. Delegates rotated frequently, and attendance was often poor, making consistent governance difficult.

Despite these immense difficulties, Congress persevered. It ratified treaties, appointed ambassadors, established a rudimentary postal service, and provided a central point of communication and coordination for the war effort. It moved locations multiple times to avoid British capture, holding sessions in Baltimore, Lancaster, York, Princeton, and Trenton before finally returning to Philadelphia.

The Articles of Confederation: A Flawed First Draft (1781-1789)

Even as the war raged, Congress recognized the need for a more permanent form of government. The Articles of Confederation, drafted in 1777 and finally ratified by all states in 1781, represented the new nation’s first constitution. It created a "firm league of friendship" among the states, reflecting a deep-seated fear of a powerful central government reminiscent of the British monarchy.

Under the Articles, Congress was the sole branch of the national government. There was no executive or judicial branch. It could declare war, make treaties, and coin money, but crucially, it lacked the power to tax or to regulate interstate commerce. It could only request funds from the states, which often ignored such requests. Each state, regardless of size, had one vote, and major legislation required the assent of nine states, while amendments required unanimity.

While the Articles successfully guided the nation through the final years of the war and negotiated the Treaty of Paris in 1783, officially ending hostilities, its weaknesses soon became glaringly apparent. The inability to raise revenue crippled its ability to pay war debts or maintain a standing army. Interstate trade disputes festered, and the national government was powerless to enforce treaties or put down internal rebellions, such as Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts. The Continental Congress, operating under the Articles, found itself increasingly ineffective and marginalized.

Legacy and Enduring Impact

The Continental Congress, in its various iterations, effectively ceased to function as a governing body with the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and the establishment of the new federal government in 1789. Its final session as the Congress of the Confederation concluded on March 2, 1789, just two days before the new Congress convened.

Yet, its legacy is profound and enduring. It was a revolutionary body that dared to declare independence from the most powerful empire in the world. It managed, against incredible odds, to prosecute a successful war for liberation, securing foreign alliances and negotiating a favorable peace treaty. It established the core principles of American governance: self-determination, popular sovereignty, and individual rights, enshrined in the Declaration of Independence.

The Continental Congress was far from perfect. It was often inefficient, underfunded, and plagued by internal divisions. Its first attempt at a national government, the Articles of Confederation, proved too weak to sustain the young republic. However, its very struggles and failures highlighted the need for a stronger, more cohesive federal structure, directly paving the way for the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

In essence, the Continental Congress was the crucible in which American nationhood was forged. It was the collective will of diverse colonies, reluctantly yet resolutely uniting to secure their freedom. It stands as a testament to the power of collective action, the courage to challenge tyranny, and the arduous, often messy, process of building a nation from scratch. Its story is not just one of revolution, but of the very first, vital steps on the long and winding road of American self-governance.