The Unfolding Triumph: How the Union Forged Victory in the American Civil War

By Our Military History Correspondent

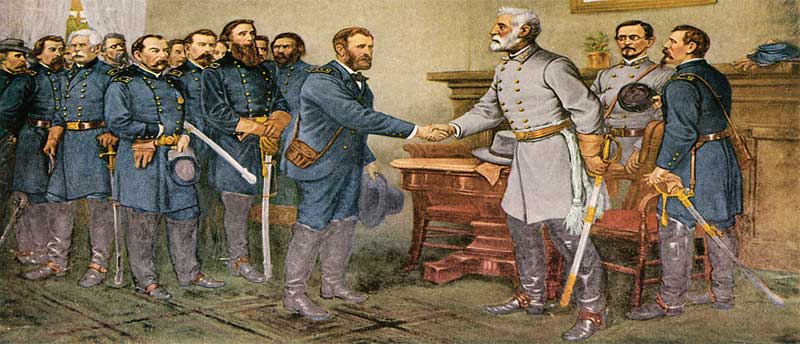

WASHINGTON D.C. – On April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, General Robert E. Lee’s surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant marked the symbolic end of the American Civil War. It was a moment of profound relief and triumph for the Union, a culmination of four years of brutal conflict that had threatened to tear the young nation asunder. Yet, this victory was far from inevitable. It was forged through a complex interplay of strategic brilliance, overwhelming industrial might, political steadfastness, and the unwavering will of millions.

The war began in April 1861 with a burst of Southern confidence and a series of Confederate victories that shocked the Union. The First Battle of Bull Run, just months after the firing on Fort Sumter, saw Union forces routed, sending a clear message: this would be no quick skirmish. For the next two years, the Confederacy, buoyed by superior military leadership in figures like Lee and Stonewall Jackson, often seemed to hold the upper hand, particularly in the Eastern Theater. McClellan’s cautious campaigns, Burnside’s disaster at Fredericksburg, and Hooker’s defeat at Chancellorsville painted a grim picture for Washington.

The Shifting Tides: 1863 – The Year of Decision

The turning point, however, arrived in the summer of 1863. The twin blows of Gettysburg and Vicksburg fundamentally altered the trajectory of the war. In Pennsylvania, from July 1st to 3rd, Union Major General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac decisively defeated Lee’s invasion of the North. Pickett’s Charge, a desperate frontal assault on the Union center on the final day, was repulsed with catastrophic losses for the Confederates. "It was the high tide of the Confederacy," historian James McPherson noted, signifying the last serious attempt by Lee to carry the war into Union territory.

Simultaneously, thousands of miles to the west, Ulysses S. Grant was laying siege to Vicksburg, Mississippi, a vital Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. After a grueling campaign, the city fell on July 4th, 1863. The capture of Vicksburg, combined with the earlier fall of Port Hudson, Louisiana, gave the Union complete control of the Mississippi River, effectively splitting the Confederacy in two and severing crucial supply lines. The loss of Vicksburg, alongside Gettysburg, was a psychological and strategic blow from which the South would never fully recover.

The Anaconda Tightens: Strategic Vision and Relentless Pressure

While dramatic battles often grab headlines, the Union’s victory was also a testament to its overarching strategic vision, encapsulated by General Winfield Scott’s early "Anaconda Plan." This plan, initially ridiculed, called for a naval blockade of Southern ports to cut off trade and supplies, combined with a thrust down the Mississippi River to divide the Confederacy. By 1863, both components were largely in place and proving devastatingly effective.

The naval blockade, though porous at times, significantly crippled the Southern economy. Blockade runners could only bring in a fraction of what was needed, leading to severe shortages of manufactured goods, medical supplies, and even basic foodstuffs. "The blockade was a constant drain on Confederate resources and morale," observed one Union naval officer. It prevented the South from leveraging its "King Cotton" diplomacy to gain formal recognition and aid from European powers like Great Britain and France, who, while sympathetic to the Southern cause, were unwilling to risk war with the Union without a clear Confederate victory on the battlefield and a guaranteed supply of cotton.

After 1863, the Union found its most effective military leaders in Ulysses S. Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman. Grant, elevated to General-in-Chief in March 1864, understood the war’s grim arithmetic: the Union had superior manpower and resources, and he was willing to use them in a war of attrition. His Overland Campaign of 1864, a relentless push against Lee’s forces in Virginia, involved continuous fighting and staggering casualties on both sides, but it steadily wore down the Army of Northern Virginia. Grant famously stated, "I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer." It took longer than summer, but his relentless pressure was unbearable for the Confederates.

Sherman, Grant’s equally formidable counterpart, revolutionized warfare with his concept of "total war." His infamous March to the Sea in late 1864, after the capture of Atlanta, saw his army cut a swath of destruction across Georgia, destroying railroads, factories, and anything that could support the Confederate war effort. "War is hell," Sherman famously declared, and his march aimed to break the South’s will to fight by bringing the harsh realities of conflict directly to its civilian population. This campaign, followed by a similarly destructive march through the Carolinas, devastated the Confederate heartland and further crippled its ability to resist.

The Unseen Hand: Industrial Might and Demographic Superiority

Beyond military strategy, the Union possessed overwhelming advantages that, while not immediately decisive, proved critical in a protracted conflict. The North’s industrial capacity dwarfed that of the agrarian South. Union factories churned out rifles, cannons, ammunition, uniforms, and railroad tracks at a rate the Confederacy could only dream of. The North’s extensive railroad network allowed for rapid troop movements and efficient supply logistics, a stark contrast to the South’s fragmented and often dilapidated rail system.

Economically, the Union’s financial institutions were more robust, capable of raising vast sums through bonds and taxes to fund the war effort. The South, reliant on agricultural exports and struggling with inflation due to over-issuance of paper money, found it increasingly difficult to sustain its armies.

Demographically, the scales were heavily tipped. The Union had a population of approximately 22 million free citizens, compared to the Confederacy’s 9 million, of whom 3.5 million were enslaved. This numerical superiority allowed the Union to absorb heavy losses and replenish its ranks, while the South, with a smaller pool of white males of fighting age, found its manpower reserves dwindling rapidly.

Crucially, the Emancipation Proclamation, issued by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, transformed the moral and practical dimensions of the war. By declaring enslaved people in Confederate territory free, Lincoln not only infused the Union cause with a powerful moral imperative but also opened the door for African Americans to join the Union army. Approximately 180,000 African American soldiers, many of them formerly enslaved, served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT), playing a vital role in Union victories and demonstrating immense courage on battlefields like Port Hudson and Fort Wagner. Their participation not only bolstered Union ranks but also denied the Confederacy a significant labor force.

Political Steadfastness and Southern Disunity

Abraham Lincoln’s political genius and unwavering resolve were equally indispensable. Despite early military setbacks, fierce political opposition, and mounting casualties, Lincoln never wavered in his commitment to preserving the Union. His leadership, his ability to articulate the war’s purpose in speeches like the Gettysburg Address, and his shrewd management of his generals were crucial. He replaced ineffective commanders until he found Grant, a man who shared his vision for a relentless prosecution of the war.

Conversely, the Confederacy, founded on the principle of states’ rights, often suffered from internal disunity. Governors sometimes prioritized their states’ needs over the central Confederate government, hindering coordination and resource allocation. While Confederate President Jefferson Davis was dedicated, he lacked Lincoln’s political flexibility and ability to inspire broad public support beyond the initial patriotic fervor.

The Final Collapse

By 1865, the Confederacy was exhausted. Its armies were starved, poorly clothed, and desperately short of ammunition. Desertion rates soared as soldiers, many of whom had fought valiantly for years, saw their homes devastated and their cause increasingly hopeless. Lee’s valiant but dwindling Army of Northern Virginia, starved out of Petersburg and Richmond, made a final desperate dash westward, hoping to link up with General Joseph E. Johnston’s forces in North Carolina. But Grant’s relentless pursuit, combined with Sheridan’s cavalry, cut off their escape.

At Appomattox, the surrender terms were magnanimous: Confederate soldiers were paroled and allowed to return home, taking their horses and mules for spring planting. Grant’s generosity was a clear signal of reconciliation, a step towards healing the fractured nation.

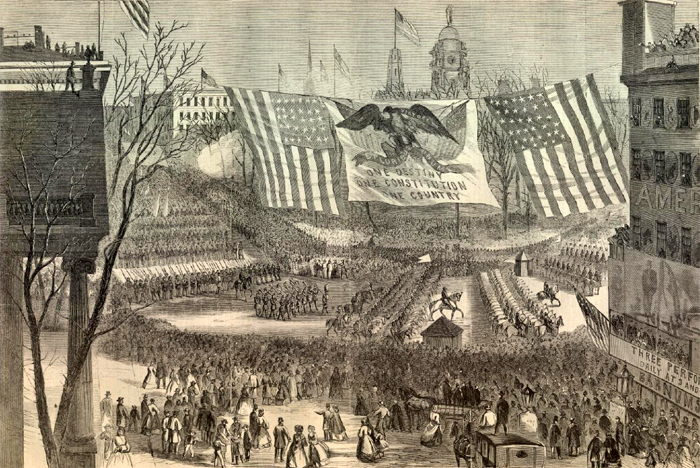

The Union’s triumph was not merely a military victory; it was a testament to the enduring power of a nation that, despite its profound internal divisions, ultimately found the collective will and resources to preserve itself. The cost was immense – over 620,000 Americans dead, untold devastation, and deep scars that would take generations to heal. Yet, the victory ensured the United States remained one nation, abolished slavery, and set the stage for a new chapter in American history, albeit one still fraught with challenges. The lessons learned from the "unfolding triumph" continue to resonate, reminding us of the fragility of unity and the immense sacrifices required to preserve it.