James Buchanan: The Unmaking of a Nation

In the annals of American presidential history, few figures loom as tragically as James Buchanan. Often ranked by historians as one of the nation’s worst, his four years in the White House (1857-1861) coincided with, and arguably accelerated, the nation’s catastrophic slide into civil war. A career politician with decades of experience, Buchanan ascended to the highest office at the precise moment the nation’s foundational cracks were widening into chasms. Was he a hapless victim of an impossible era, or a deeply flawed leader whose actions and inactions proved disastrous? The journalistic lens offers a compelling, if unsettling, look at the man who presided over the unraveling of the United States.

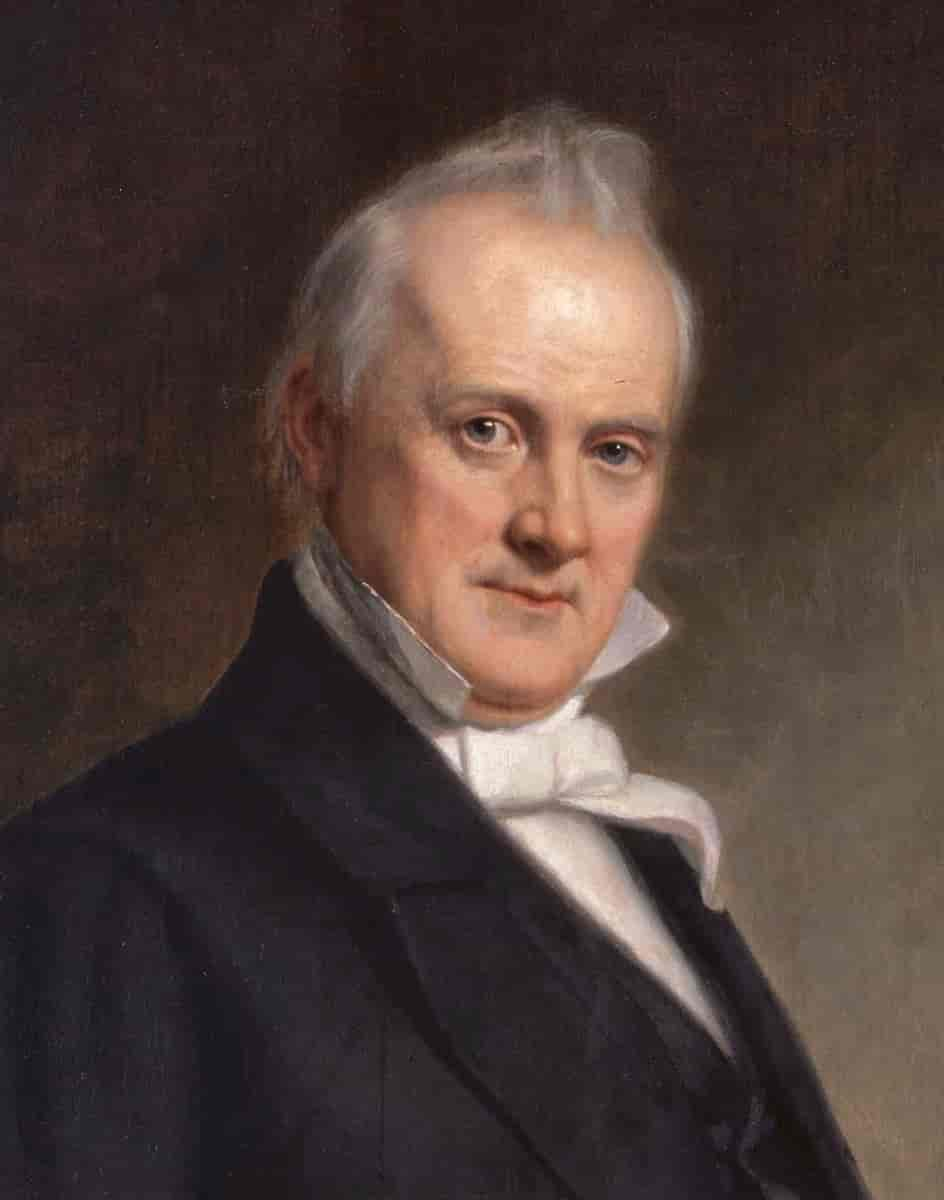

Born in 1791 in Cove Gap, Pennsylvania, James Buchanan was a figure seemingly tailor-made for political prominence. He was a lawyer by profession, astute and meticulous, and his political career was long and distinguished, spanning nearly five decades before his presidency. He served in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, the U.S. House, and the U.S. Senate. He was Minister to Russia under Andrew Jackson and Secretary of State under James K. Polk, during which time he played a key role in the Oregon boundary dispute and the annexation of Texas. His diplomatic experience was further burnished as Minister to the United Kingdom under Franklin Pierce. This extensive resume, coupled with his absence from the country during the most heated debates over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, made him a palatable, "safe" choice for the Democratic Party in 1856. He was also the only bachelor president, a detail that, while seemingly minor, added to his somewhat enigmatic persona.

However, Buchanan was also a "Doughface" – a Northerner with Southern sympathies. He firmly believed in states’ rights, the legality of slavery where it existed, and the importance of appeasing the South to preserve the Union. This deeply ingrained political philosophy, once seen as a unifying force, would become his greatest liability as the nation fractured.

A Presidency Plagued from the Start

Buchanan’s inauguration in March 1857 was immediately overshadowed by a seismic event: two days later, the Supreme Court delivered its infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford decision. The ruling declared that African Americans, whether enslaved or free, could not be American citizens and therefore had no standing to sue in federal court. More devastatingly, it declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, asserting that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in the territories.

Buchanan, who had prior knowledge of the ruling and subtly pressured one of the justices to vote with the majority, hailed it as a definitive solution to the slavery question. "This is a judicial question," he declared in his inaugural address, "which legitimately belongs to the Supreme Court of the United States, before whom it is now pending; and, happily, the question is a judicial one, which from its nature is to be decided by the highest tribunal of the country." His hope was that the Court’s decree would end the political strife. Instead, it ignited a firestorm, further polarizing the nation and fueling Northern outrage. Far from settling the issue, Dred Scott poured gasoline on the flames, rendering all legislative compromises on slavery in the territories effectively moot and confirming Northern fears of a powerful "Slave Power" conspiracy.

Bleeding Kansas and the Lecompton Fiasco

If Dred Scott was the match, Kansas was the powder keg. The territory had been a battleground since the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 allowed its settlers to decide whether it would be free or slave (popular sovereignty). Violence had erupted between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions, earning it the grim moniker "Bleeding Kansas."

Buchanan, committed to popular sovereignty and Southern rights, made a critical misstep with the Lecompton Constitution. This pro-slavery document, drafted by a convention of mostly pro-slavery delegates, was widely believed to be fraudulent and did not genuinely represent the will of the majority of Kansans. Despite its dubious origins and the vehement opposition of Kansas’s free-state majority, Buchanan urged Congress to admit Kansas as a slave state under the Lecompton Constitution.

His advocacy for Lecompton alienated powerful figures within his own party, most notably Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, the architect of popular sovereignty, who recognized the fraud and declared that "fairness and justice" demanded a new, legitimate vote. Buchanan’s stubbornness fractured the Democratic Party, weakening its national power and further eroding trust between North and South. The Lecompton Constitution was ultimately rejected, but the political damage to Buchanan and the nation was irreparable. His actions confirmed Northern suspicions that he was a tool of the Southern slave interests, further hardening sectional lines.

Economic Woes and Diplomatic Blunders

Beyond the escalating sectional crisis, Buchanan’s presidency was also marked by the Panic of 1857, a severe economic downturn triggered by railroad overexpansion and declining grain prices. While not directly his fault, the panic added to the national malaise and highlighted the government’s limited tools for economic intervention at the time.

Earlier in his career, as Minister to Britain, Buchanan had also been involved in the infamous Ostend Manifesto (1854). This secret diplomatic dispatch, co-authored by Buchanan, urged the U.S. to purchase Cuba from Spain, and if Spain refused, to seize it by force. The manifesto was intended to expand U.S. territory and potentially add another slave state, but it was leaked to the press and widely condemned as a pro-slavery scheme and an aggressive, imperialistic foreign policy. While this occurred before his presidency, it colored perceptions of his pro-Southern leanings and his willingness to pursue controversial policies to expand slave territory.

The Secession Crisis: A President Paralyzed

The true test of Buchanan’s leadership came in the aftermath of Abraham Lincoln’s election in November 1860. The victory of the Republican Party, founded on an anti-slavery expansion platform, was the signal for Southern states to act on their long-held threats of secession. South Carolina led the way on December 20, 1860, followed swiftly by six other states (Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas) before Buchanan left office in March 1861.

Faced with the disintegration of the Union, Buchanan was paralyzed by his strict interpretation of the Constitution. He believed, as he stated in his final annual message to Congress, that "no State has a right to secede from the Union," but also that "the Executive has no power to coerce a State into submission which is attempting to withdraw." This legalistic stance left him in an impossible bind: he condemned secession as illegal but saw no constitutional authority to prevent it.

His policy became one of indecision and inaction. He sought compromise, supporting the Crittenden Compromise, which proposed constitutional amendments to protect slavery in the territories and guarantee its existence in states where it already existed. However, this last-ditch effort failed, rejected by Republicans who refused to concede on the expansion of slavery.

Buchanan’s inaction during these critical months allowed the secessionist movement to gain irreversible momentum. Southern states seized federal arsenals, custom houses, and forts with little resistance. His most significant act was sending the unarmed merchant ship Star of the West to resupply Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor in January 1861. The ship was fired upon by South Carolina batteries and forced to retreat, a humiliating incident that foreshadowed the coming conflict.

By the time Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated on March 4, 1861, Buchanan had handed him a nation on the brink. Seven states had already seceded, forming the Confederate States of America. Federal authority in the South had all but collapsed.

Legacy: The Scapegoat or the Architect of Disaster?

Upon leaving office, a visibly relieved Buchanan famously remarked to Abraham Lincoln, "My dear sir, if you are as happy on entering the White House as I am on leaving it, you are a very happy man indeed." He retired to his Wheatland estate in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he spent his remaining years defending his actions, publishing "Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of Rebellion" in 1866. He argued that he had acted within the confines of the Constitution and that the crisis was the culmination of decades of sectional strife, not solely his doing.

While it is true that Buchanan inherited an almost insurmountable crisis, his specific actions and inactions are difficult to defend. His unwavering support for the fraudulent Lecompton Constitution, his complicity in the Dred Scott decision, and his legalistic paralysis during the secession crisis arguably accelerated the nation’s collapse. He prioritized constitutional interpretations that favored Southern interests over the practical necessity of holding the Union together. He failed to project strong leadership when it was most desperately needed, allowing the forces of disunion to gather strength unchallenged.

Historians continue to debate the degree of his culpability. Some argue that the forces unleashed in the 1850s were simply too powerful for any president to contain, and that Buchanan, like all his predecessors, was a product of his time. Others contend that his particular blend of timidity, pro-Southern bias, and strict constitutionalism made him uniquely unsuited for the challenges he faced, turning a perilous situation into an inevitable catastrophe.

Regardless of the precise apportionment of blame, James Buchanan’s presidency stands as a stark reminder of the immense pressures that can tear a nation apart and the profound impact of leadership – or its absence – in times of extreme crisis. He remains a poignant symbol of a nation’s descent into its darkest hour, the last leader before the storm truly broke.