Oklahoma’s Silent Stretch: Unearthing the Santa Fe Trail’s Arduous Legacy

When one conjures images of the historic Santa Fe Trail, the mind often drifts to the bustling starting points in Missouri, the dramatic landscapes of Kansas, or the arid beauty of New Mexico. Less frequently, however, do thoughts turn to the vast, windswept plains of Oklahoma. Yet, for nearly six decades, a critical and exceptionally challenging segment of this iconic trade route snaked through what would eventually become the Oklahoma Panhandle, leaving an indelible, albeit often overlooked, legacy on the land and the nation’s westward expansion.

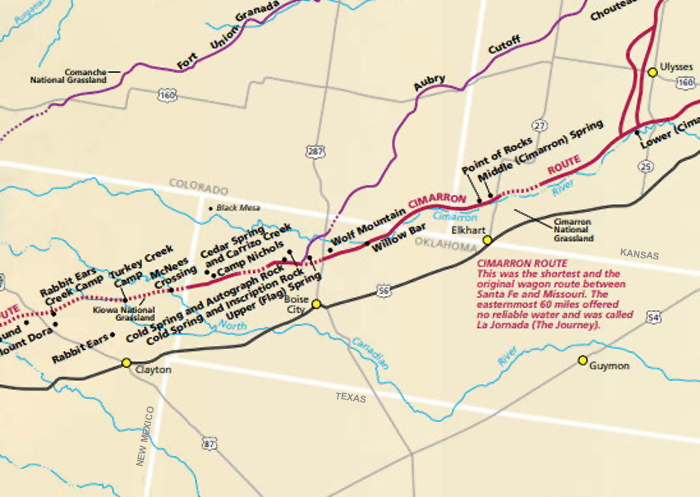

The Santa Fe Trail, established in 1821 by William Becknell, was more than just a path; it was a vital artery of commerce and conquest, connecting the burgeoning United States with the distant Mexican territories. Stretching roughly 800 miles from Franklin (later Independence), Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, it facilitated the exchange of goods, cultures, and ideas, playing a pivotal role in the economic and political development of the American West. While much of the trail followed two main branches—the Mountain Route and the Cimarron Cutoff—it was the latter, a shorter but infinitely more perilous journey, that sliced through the heart of what early travelers dubbed the "Great American Desert," and what we now know as Oklahoma’s remote Panhandle.

The Cimarron Cutoff, preferred for its relative flatness and shorter distance, saved traders significant time and effort compared to the mountainous northern route. However, this convenience came at a severe cost: a notorious lack of water and the constant threat of encounters with powerful Native American tribes who viewed the increasing influx of American traders with a mixture of curiosity, opportunity, and deep suspicion. For approximately 150 miles, the trail traversed the parched, desolate landscape of present-day Cimarron County, Oklahoma, demanding unparalleled resilience from those who dared to cross it.

The Perilous Passage: Oklahoma’s Key Sites

The Oklahoma stretch of the Santa Fe Trail was not marked by grand forts or bustling settlements, but by essential, life-sustaining oases – natural springs and river crossings that became critical waypoints in a land that offered little respite. These sites, though often subtle and easily missed by the modern eye, represent the very essence of survival on the frontier.

One of the most crucial points was the Upper Cimarron Crossing, located near the western border of Oklahoma with New Mexico. Here, the Cimarron River, often a mere trickle or even dry during the summer months, could transform into a formidable, quicksand-ridden barrier after heavy rains. Wagons, loaded with thousands of pounds of merchandise, would frequently bog down, requiring immense effort to extract. This crossing marked a significant psychological waypoint, signaling that the worst of the dreaded "Jornada" – the long, dry stretch of the Cimarron Desert – was either just beginning or finally ending. Accounts from travelers speak of the profound relief or dread associated with this fickle waterway. "The Cimarron, a river only in name for much of the year, proved to be our greatest torment," wrote one anonymous diarist in the 1840s, "Its sandy bed swallowed wagons whole, and its elusive waters left us parched."

Further east, deeper into the heart of Oklahoma’s Panhandle, lay a series of vital springs that became legendary among trail users. Cold Spring, located southwest of Boise City, was arguably the most celebrated. Its reliable, clear, and indeed, cold water offered a literal lifeline in a region where surface water was exceedingly scarce. Travelers often described it as a true oasis, a place where exhausted animals could be watered and weary humans could finally quench their desperate thirst. Its strategic importance made it a frequent campsite, and many a desperate prayer was likely offered in thanks for its life-giving bounty. The stark contrast between the parched surroundings and the spring’s cool waters made it an unforgettable landmark.

Just a few miles east of Cold Spring was Middle Spring. While not as voluminous as Cold Spring, it was equally important, serving as another essential watering hole and a testament to the meticulous planning and knowledge required to navigate this harsh environment. These springs were not just points on a map; they were beacons of hope, their locations meticulously recorded in guidebooks and passed down through generations of traders and teamsters. The very existence of the trail through this area hinged on the consistent availability of these natural water sources.

Another significant location was Willow Bar, further east along the trail, characterized by the presence of willow trees – a clear indicator of underground water. Like Cold Spring and Middle Spring, it provided a much-needed stop for rest and replenishment before or after traversing the longest waterless stretches. These natural features, though seemingly minor, dictated the pace and survivability of the entire journey.

The Human Element and Native American Encounters

The Santa Fe Trail, particularly the Cimarron Cutoff, was a crucible that tested the limits of human endurance. Travelers faced extreme temperatures, from scorching summer heat that could crack the earth to sudden, brutal blizzards in winter. The ever-present threat of thirst was paramount; many accounts tell of agonizing journeys where water rations dwindled to nothing, and men and animals alike collapsed from dehydration. Disease, accidents, and the sheer monotony of endless plains added to the immense challenges. "Every mile was a struggle, every drop of water a blessing," recounted a veteran freighter. "The Cimarron country was a land that sought to break you, body and spirit."

Adding to the natural perils were the complex and often dangerous interactions with the Native American tribes who inhabited these lands. The Comanche and Kiowa, powerful equestrian tribes, dominated the Southern Plains. While some interactions involved trade—exchanging American goods for horses, buffalo hides, and other native products—many encounters were fraught with tension. The trail cut directly through their traditional hunting grounds, particularly those of the buffalo, a vital resource. As American traffic increased, so did competition for resources and resentment over incursions.

For the Native Americans, the trail was a double-edged sword. It brought new goods and opportunities for trade, but it also brought disease, encroaching settlers, and a direct challenge to their sovereignty. Raids on wagon trains for horses and provisions became increasingly common, especially during the later decades of the trail’s operation, leading to skirmishes and a constant state of vigilance for the traders. Military escorts became necessary, and small outposts were occasionally established to protect the flow of commerce. The narrative of the Santa Fe Trail in Oklahoma is incomplete without acknowledging the profound impact it had on these indigenous peoples and their struggle to maintain their way of life against the relentless tide of westward expansion.

A Legacy Preserved

The advent of the railroad in the late 1870s gradually rendered the Santa Fe Trail obsolete. By 1880, the rail lines had reached Santa Fe, offering a faster, safer, and more efficient means of transport. The wagons fell silent, the ruts slowly faded, and the tales of the trail became the stuff of legend.

Today, the Santa Fe National Historic Trail, administered by the National Park Service, works to preserve and interpret the remnants of this epic journey. While many of Oklahoma’s trail sites are on private land, efforts are ongoing to mark and protect accessible sections. Historical markers dot the landscape, offering glimpses into the past, and dedicated local historical societies work tirelessly to educate the public about this vital chapter in the state’s history.

Visiting these sites in Oklahoma today is a profoundly different experience than it would have been for a 19th-century traveler. The paved roads, modern vehicles, and vast agricultural fields mask the raw, untamed nature of the original journey. Yet, standing at Cold Spring or near the Cimarron River, one can still feel a tangible connection to the past. The endless horizon, the vastness of the sky, and the quiet whisper of the wind can evoke a sense of the isolation and challenge that defined the trail experience.

The Oklahoma stretch of the Santa Fe Trail serves as a powerful reminder of the human spirit’s capacity for endurance, the harsh realities of frontier life, and the complex interplay between commerce, expansion, and indigenous cultures. It is a silent testament to the thousands of individuals—traders, teamsters, soldiers, and Native Americans—whose lives intersected on these plains, forging a path that helped shape the destiny of a nation. While often overshadowed by its more famous segments, Oklahoma’s contribution to the Santa Fe Trail’s legacy is no less significant, a rugged and essential chapter in the grand narrative of the American West. It beckons to those willing to look beyond the obvious, to unearth the stories etched into the very fabric of the land.