The Crucible of Conflict: Camp Union and the Shaping of Kansas City’s Civil War Identity

KANSAS CITY, MO – In the early months of 1861, as the United States teetered on the brink of civil war, Kansas City was a rough-and-tumble frontier town, a strategic river port at the crossroads of diverging loyalties. Its population was barely a few thousand, a mix of ambitious merchants, rugged frontiersmen, and a growing number of German and Irish immigrants. But with the firing on Fort Sumter and Missouri’s agonizing decision to remain in the Union, albeit with deep pro-Confederate sympathies simmering just beneath the surface, this sleepy outpost was about to be transformed into a vital military hub: Camp Union.

More than just a temporary encampment, Camp Union became the beating heart of Union military operations in Western Missouri, a crucible where raw recruits were forged into soldiers, supplies were stockpiled for distant campaigns, and the very identity of Kansas City was indelibly shaped by the conflict. For four long years, its sounds – the rhythmic drumbeats, the bugle calls, the shouts of drill sergeants, the clatter of wagons, and the mournful strains of "Taps" – became the city’s constant soundtrack.

The Genesis of a Garrison

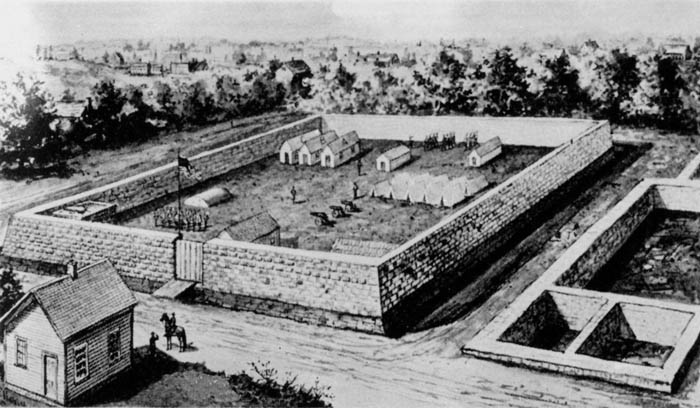

Kansas City’s strategic importance lay in its confluence of the Missouri River and its position as a gateway to the western territories. It was a natural point for military control, allowing Union forces to project power into the often-volatile border region. Almost immediately after the war began, federal authorities recognized this. Land in the city’s West Bottoms, a flat floodplain prone to flooding but offering ample space for barracks, parade grounds, and logistical operations, was quickly appropriated.

"It was a necessity, plain and simple," explained Dr. William R. Miles, a local historian specializing in the Civil War era. "Missouri was a vital border state, and Kansas City was its westernmost bastion. Without a strong military presence, the city would have been overrun, and the entire Missouri River lifeline would have been jeopardized."

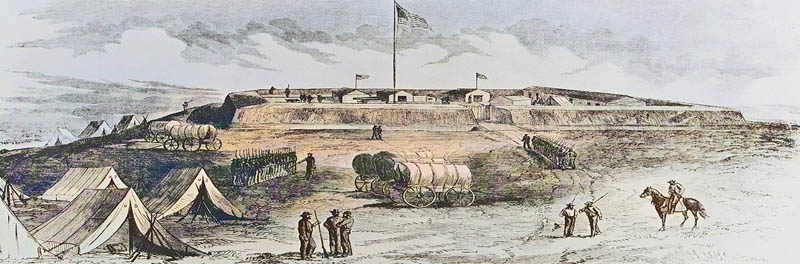

By late 1861, Camp Union was a bustling cantonment. Crude wooden barracks, tents, mess halls, and administrative buildings sprang up. Trenches and earthworks were dug to defend against potential Confederate incursions. The sounds of construction mingled with the cries of teamsters and the constant activity of thousands of men.

Life in the Lines: Drill, Discipline, and Disease

For the soldiers stationed at Camp Union, life was a grueling mix of monotonous routine and the constant threat of violence. Regiments from Missouri, Kansas, Iowa, and even Illinois passed through its gates, undergoing training that was often rudimentary but essential.

A typical day began before dawn, marked by reveille and the call for roll. Mornings were dominated by drill – marching, weapons practice, and tactical maneuvers. "You could hear the crack of muskets and the roar of command echoing through the West Bottoms from sunup to sundown," recalled a local resident in a post-war memoir. "It was a constant reminder that war was at our doorstep."

Discipline was strict, enforced by officers often as green as their recruits. Punishments for insubordination, desertion, or drunkenness were harsh, ranging from extra duty to public humiliation. Yet, camaraderie flourished. Soldiers formed bonds that would last a lifetime, sharing meager rations, writing letters home, and dreaming of the day the war would end.

The greatest enemy within the camp, however, was not the Confederates but disease. Poor sanitation, crowded conditions, and a lack of understanding of germ theory meant that measles, dysentery, typhoid, and smallpox swept through the ranks with devastating efficiency. Hospitals, often little more than converted buildings, were overwhelmed. It was not uncommon for more soldiers to die from illness than from enemy fire. "The graveyards around Kansas City swelled with the bodies of young men who never saw a battle," observed a contemporary newspaper account.

A City Transformed: Economic Boom and Social Strain

Camp Union didn’t just transform soldiers; it transformed Kansas City. The influx of thousands of troops and associated personnel created an economic boom. Local merchants thrived, selling everything from uniforms to foodstuffs. Saloons and boarding houses proliferated. Employment opportunities, particularly for laborers, expanded rapidly.

However, this boom came with significant social strain. The city’s small population struggled to accommodate the sudden influx. Prices for goods and housing skyrocketed. The constant presence of armed men, many far from home and prone to boredom or mischief, led to an increase in crime and social unrest.

"Kansas City became a military city overnight," noted historian Miles. "Its identity shifted from a frontier trading post to a vital cog in the Union war machine. This rapid militarization left an indelible mark on its development."

The Contraband and the Colored Troops

Perhaps one of the most significant and often overlooked aspects of Camp Union was its role in the lives of enslaved African Americans. As Union forces pushed into Missouri, thousands of enslaved people, seizing the opportunity for freedom, fled their plantations and sought refuge behind Union lines. These individuals, often referred to as "contraband of war," arrived at Camp Union seeking protection, food, and shelter.

The camp became a temporary haven for many. While conditions were often rudimentary, and the promise of true freedom was still distant, it offered a glimpse of a different future. Many of these "contraband" began working for the Union army, performing vital tasks like cooking, cleaning, and constructing fortifications.

Crucially, Camp Union also became a recruitment center for the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Initially, Black soldiers were met with skepticism and prejudice, even within the Union ranks. But their courage and determination quickly silenced critics. Regiments like the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry (later redesignated the 79th U.S. Colored Infantry) and others that passed through Camp Union proved their mettle in battles across the region.

"To fight for your own freedom, to put on that uniform, it was a powerful statement," said Sarah Jennings, a descendant of a USCT soldier who served in Missouri. "My great-great-grandfather always said that joining the Union Army wasn’t just about winning the war; it was about proving our humanity, proving our right to be free citizens." The sight of Black soldiers drilling alongside white soldiers, though still segregated, was a revolutionary one in a state deeply divided over slavery.

Defending the Border: From Quantrill’s Shadow to Westport’s Fury

Camp Union’s strategic importance was underlined by the constant threat of Confederate raids and guerrilla warfare. William Quantrill’s infamous raid on Lawrence, Kansas, in 1863, though not directly attacking Kansas City, sent shockwaves through the region and heightened the city’s defensive posture. Soldiers from Camp Union were often dispatched to counter these threats, patrolling the countryside and protecting Union sympathizers.

The camp’s ultimate test came in October 1864, during the pivotal Battle of Westport, often called "The Gettysburg of the West." Confederate Major General Sterling Price launched a massive raid into Missouri, aiming to capture St. Louis and Jefferson City. Kansas City, with Camp Union at its core, became a primary objective.

Union forces, commanded by Major General Samuel R. Curtis and Major General Alfred Pleasonton, converged on Kansas City. Troops from Camp Union played a critical role in the city’s defense and the subsequent pursuit of Price’s army. The battle, fought just south of the city, was a decisive Union victory, effectively ending Confederate military operations in Missouri. The defenses and logistical infrastructure built around Camp Union were instrumental in facilitating the Union triumph.

The Legacy of a Lost Camp

With the surrender of Robert E. Lee at Appomattox in April 1865, the war ended, and Camp Union’s purpose evaporated. The thousands of soldiers who had called it home began to muster out, returning to their farms and families. The wooden barracks were dismantled, the earthworks leveled, and the vast expanse of the West Bottoms slowly reverted to its pre-war state, eventually becoming a bustling industrial and rail hub. Today, there are no visible remains of Camp Union. The land it occupied is now covered by rail yards, warehouses, and modern infrastructure, including the approach to the iconic Liberty Memorial.

Yet, Camp Union’s legacy endures. It was a place where national conflict played out on a local scale, where disparate individuals were united by a common cause, and where the promise of freedom began to take tangible shape for many. It transformed Kansas City from a fledgling outpost into a significant regional center, its wartime experience shaping its subsequent growth and character.

"Camp Union was more than just a collection of tents and barracks," concluded Dr. Miles. "It was a symbol of Union resolve, a crucible of change, and a vital chapter in Kansas City’s story. Though physically gone, its impact on the city’s identity and its role in the larger narrative of the Civil War remains profound." The ghosts of those long-ago soldiers, the echoes of their drills and their dreams, still resonate in the very foundations of Kansas City.