The Crucible of Liberty: Unveiling the Human Tapestry of the American Revolution

The American Revolution, often distilled into images of bewigged gentlemen signing declarations and resolute soldiers battling redcoats, was in reality a far more complex and diverse human drama. It was not solely the brainchild of a few enlightened elites, but a grand, often brutal, experiment forged by an astonishing array of individuals – from the most famous architects of independence to the unsung heroes, the marginalized, and even those who chose to remain loyal to the crown. Their collective struggles, sacrifices, and competing visions illuminate the true depth of this foundational conflict.

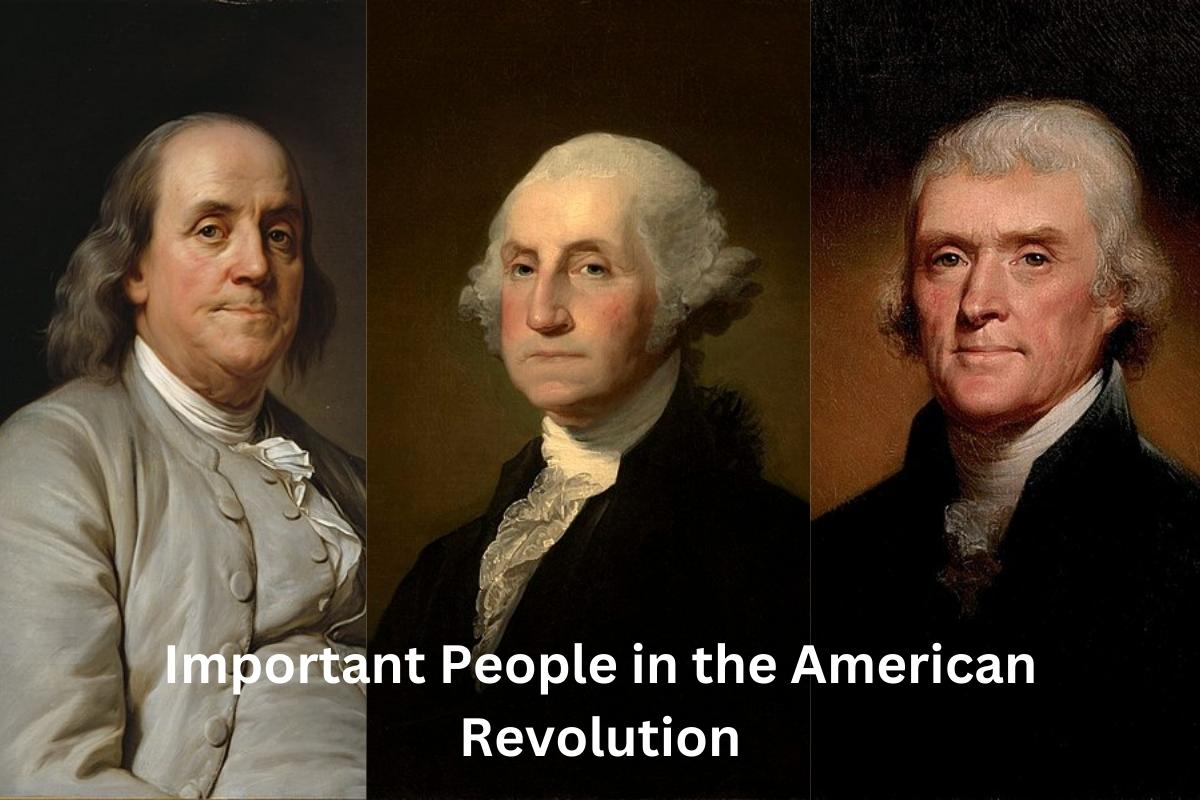

At the very heart of the Revolution were the Founding Fathers, a collection of brilliant, flawed, and fiercely determined men whose intellectual prowess and political courage steered the nascent nation. Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, articulated the soaring ideals of liberty and equality that fueled the cause. His words, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness," became the bedrock of American identity, even as their full realization would take centuries.

John Adams, a tireless advocate for independence and a skilled legal mind, was often described as the "Atlas of Independence" for his relentless efforts in the Continental Congress. Though less charismatic than Jefferson, his unwavering conviction and foresight were indispensable. He famously wrote to his wife Abigail, "The die is cast. The Rubicon is crossed."

Then there was Benjamin Franklin, the sage diplomat and polymath, whose wit, wisdom, and international renown were crucial in securing the vital alliance with France. His presence in Paris lent credibility to the American cause, and his strategic genius helped secure the financial and military aid that proved pivotal. Franklin embodied the Enlightenment spirit, a man of science, invention, and profound common sense.

But the Revolution needed more than just ideas; it needed a leader capable of transforming those ideals into military victory. George Washington, the stoic, resolute Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, was that indispensable figure. His leadership was not marked by brilliant battlefield maneuvers, but by his extraordinary perseverance, moral integrity, and ability to hold a ragtag army together through the bleakest of winters, most notably at Valley Forge. He understood the psychological dimension of the war. "Perseverance and spirit have done wonders in all ages," he wrote, a testament to his own enduring resolve. Washington’s decision to relinquish power after the war, rather than seizing it, set a crucial precedent for civilian control of the military in the new republic.

Beyond the iconic figures, the Revolution drew heavily upon the often-overlooked contributions of women. They were not merely passive observers but active participants. Abigail Adams, through her prolific correspondence with John, offered keen political insights and famously urged him to "Remember the Ladies," advocating for women’s rights in the new legal code. Mercy Otis Warren, a historian and playwright, used her pen to champion the patriot cause, providing intellectual and moral support through her satirical plays and later, a comprehensive history of the Revolution.

On the front lines, women like Deborah Sampson disguised themselves as men to fight, while others, like Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley, known as "Molly Pitcher," carried water to soldiers and even took up arms during battles like Monmouth. Countless other women managed farms and businesses in the absence of their husbands, nursed the sick and wounded, served as spies, and maintained the domestic economy that sustained the war effort. Their resilience was the backbone of the home front.

The promise of liberty, however, was a fraught one for African Americans. For many, the Revolution presented a profound paradox: fighting for freedom while enslaved. Yet, thousands, both free and enslaved, answered the call to arms, driven by a desire for their own liberty. Crispus Attucks, an African American sailor, was the first casualty of the Boston Massacre in 1770, often cited as the first martyr of the American cause. Later, regiments like the 1st Rhode Island Regiment were composed largely of Black soldiers, fighting bravely for a nation that largely denied them their fundamental rights.

Some, like James Armistead Lafayette, an enslaved man from Virginia, served as a crucial spy for the Continental Army, gathering intelligence from British camps while posing as a runaway slave. His contributions were so significant that Lafayette himself lobbied for Armistead’s freedom after the war. The British, notably Lord Dunmore in Virginia, also offered freedom to enslaved people who joined their ranks, highlighting the complex and often cynical racial dynamics of the conflict.

Native American tribes also found themselves caught in the maelstrom, often forced to choose sides in a conflict that threatened their lands and ways of life regardless of the outcome. The Iroquois Confederacy, for instance, was deeply divided, with the Mohawk leader Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) leading his people as British allies, while the Oneida and Tuscarora largely sided with the Americans. The Revolution ultimately proved disastrous for most Native American nations, as the expansionist policies of the new United States continued to encroach upon their territories.

Beyond the named individuals, the common soldier and citizen represented the vast majority of those who experienced the Revolution. These were farmers, artisans, merchants, and laborers who endured the brutal realities of war: disease, starvation, meager pay, and the constant threat of death. They fought for ideals, but also for their homes, families, and communities. Their resilience in the face of immense hardship, often barefoot and ill-equipped, is a testament to the popular commitment to the revolutionary cause. It was their collective will that truly fueled the "Spirit of ’76."

Crucially, the Revolution was not a universally supported movement. A significant portion of the population – an estimated 15-20% – remained Loyalists, or Tories, dedicated to the British Crown. These individuals, often wealthy landowners, merchants, or those with strong ties to Britain, viewed the rebellion as an act of treason and chaos. They believed that stability and prosperity lay with continued allegiance to the Empire. Their motivations were varied: fear of anarchy, economic interests, personal loyalty to the King, or a genuine belief in the legitimacy of British rule.

The Loyalists suffered immense persecution, including confiscation of property, public humiliation, and even violence. Many were forced into exile, resettling in Canada, Britain, or the Caribbean, leaving behind their lives and fortunes. Benedict Arnold, whose name became synonymous with treason, represents the most infamous Loyalist defection. A brilliant but embittered American general, his betrayal underscored the deep divisions and personal stakes of the conflict. His story serves as a stark reminder that allegiances were often fluid and intensely personal.

Finally, the American victory would have been impossible without the crucial assistance of foreign allies. Marquis de Lafayette, a young French aristocrat, captivated by the ideals of liberty, became a trusted general and lifelong friend to Washington. His presence symbolized the vital French commitment. Baron von Steuben, a Prussian military officer, brought discipline and training to the Continental Army at Valley Forge, transforming them from a ragged militia into a professional fighting force. The French fleet under Admiral de Grasse and the French army commanded by Comte de Rochambeau were instrumental in the decisive victory at Yorktown, sealing British defeat. These foreign figures remind us that the American Revolution was not just a domestic affair but a pivotal event in global geopolitics.

In conclusion, the American Revolution was a truly collective enterprise, far more intricate and human than its often-simplified narratives suggest. It was shaped by the eloquent pens of intellectuals, the strategic genius of military leaders, the quiet strength of women, the paradoxical fight for freedom by enslaved people, the complex loyalties of Native Americans, the steadfast courage of common citizens, the desperate struggle of Loyalists, and the indispensable aid of international partners.

The "people" of the American Revolution were not a monolithic entity but a vibrant, often contentious, tapestry of humanity. Their stories, individually and collectively, reveal the profound struggles, ideals, and compromises that birthed a nation. Understanding their diverse roles is essential to appreciating the true magnitude of the experiment in liberty that began over two centuries ago—an experiment whose enduring legacy continues to unfold today.