Paved with Salt and Peril: The Enduring Legacy of Missouri’s Boone’s Lick Road

The dust of two centuries seems to hang perpetually over the ghost of Boone’s Lick Road. Today, quiet stretches of asphalt or gravel, sometimes simply a faint scar across a farmer’s field, are all that remain of what was once Missouri’s vital artery into the American West. But peel back the layers of time, and you’ll find a path steeped in the raw ambition, brutal hardship, and unyielding spirit of pioneers who carved a nation out of wilderness.

More than just a trail, Boone’s Lick Road was a crucible. It was where the hopes of land-hungry settlers met the unforgiving realities of frontier life, where commerce blossomed amidst danger, and where the very fabric of Missouri, and indeed the trans-Mississippi West, was first woven.

The Salty Origins

The story of Boone’s Lick Road begins not with grand design, but with a humble, essential commodity: salt. In the early 1800s, before refrigeration, salt was indispensable for preserving meat, curing hides, and maintaining livestock. It was a precious commodity on the frontier, often scarce and expensive.

Enter Daniel Boone, the legendary frontiersman whose life was synonymous with westward expansion. Though often credited with the road, it was actually his sons, Nathan and Daniel Morgan Boone, who truly pioneered the route. Around 1805, they ventured into the uncharted wilds of central Missouri, drawn by tales of natural salt springs, or "licks," along the Missouri River. Near what is now Howard County, they discovered a series of rich saline springs, creating a commercial salt-making operation that quickly became a crucial source for the burgeoning settlements.

"The discovery of the Boone’s Lick salt springs was a game-changer for early Missouri," explains Dr. John R. Williams, a historian specializing in frontier economics. "It provided a readily available, local source of a vital resource, reducing dependence on costly imports and fueling the growth of communities further west."

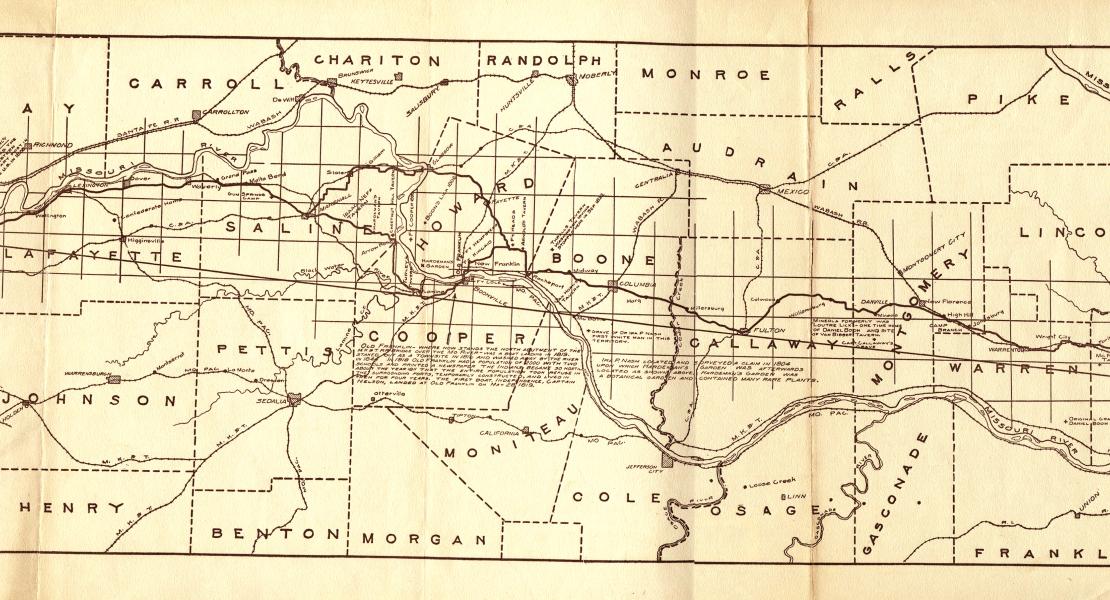

To transport their precious cargo of salt, the Boones, and others who followed, began to improve existing Native American trails and buffalo traces, forging a rough but passable path from the French trading post of St. Charles, near the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers, westward to the salt works. This rudimentary path, winding through dense forests, across treacherous creeks, and over rolling hills, became known as Boone’s Lick Road.

The Vein of Ambition: Why They Came

The road’s purpose quickly expanded beyond just salt. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 had flung open vast new territories, and Missouri, strategically positioned at the gateway to the West, became a magnet for ambitious settlers. The promise of cheap, fertile land, the chance for a new beginning, and the lure of adventure drew thousands from Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and beyond.

Boone’s Lick Road became their chosen route. It was the "main street" of early Missouri, the primary conduit for migration into the central part of the territory and a critical jump-off point for even grander ventures, including the Santa Fe Trail and later, the Oregon Trail.

"People weren’t just moving their families; they were moving their entire lives," says Sarah Thompson, a local historian and preservationist. "Imagine a wagon train, creaking under the weight of furniture, tools, seeds, and livestock, children walking alongside, driven by the dream of owning their own piece of land. That was the essence of Boone’s Lick Road."

A Grueling Pilgrimage: The Perils of the Path

The romantic image of pioneers often belies the brutal reality of their journey. Boone’s Lick Road was not a paved highway; it was a rugged, often impassable track that tested the limits of human endurance and mechanical fortitude.

Travelers faced a litany of challenges:

- Weather: Mud was a constant enemy, especially in spring and fall, swallowing wagon wheels whole and turning the road into a quagmire. In summer, the dust was suffocating, and in winter, ice and snow made passage nearly impossible.

- Terrain: The road traversed dense forests where fallen trees blocked the path, steep ravines that required careful navigation, and numerous unbridged creeks and rivers that had to be forded, often at great risk of capsizing.

- Disease: Malaria, typhoid, and other frontier ailments were rampant, claiming lives with terrifying speed. Without access to modern medicine, a simple fever could turn fatal.

- Accidents: Broken axles, runaway horses, overturned wagons, and injuries from falls were common occurrences, often leaving families stranded far from help.

- Banditry and Native American Tensions: While not as prevalent as Hollywood might suggest, isolated attacks by "road agents" (bandits) or instances of cattle rustling were a genuine concern. Relations with Native American tribes, particularly the Osage, were complex. While some interactions were peaceful, the encroachment of settlers often led to friction and occasional skirmishes, especially in the earlier years. Forts and blockhouses, like Fort Cooper and Fort Hempstead, dotted the route, offering some measure of protection.

A typical journey from St. Charles to Franklin, a distance of roughly 100 miles, could take anywhere from one to two weeks, depending on conditions. Wagons were often pulled by oxen, slow but powerful, averaging perhaps 10-15 miles a day. The constant strain on both humans and animals was immense.

The Towns That Rose and Fell

The road’s influence extended far beyond just facilitating movement; it fostered the growth of towns that became vital centers of commerce and culture.

St. Charles served as the eastern gateway, the last outpost of civilization before venturing into the interior. It was where supplies were purchased, wagons outfitted, and final goodbyes exchanged.

Further west, Franklin, established in 1816, quickly emerged as the most important town on the road. Located on the Missouri River, it became a bustling hub for trade, a political center (briefly serving as the territorial capital), and the primary outfitting point for the Santa Fe Trail. Its population swelled to over 2,000, boasting a newspaper (the Missouri Intelligencer), stores, taverns, and even a university.

But Franklin’s meteoric rise was matched by a dramatic fall. The capricious Missouri River, known for its unpredictable floods and shifting course, began to erode the town’s riverfront. Despite desperate efforts, much of Franklin was literally washed away in the late 1820s, forcing its residents to relocate to higher ground, giving birth to New Franklin.

Across the river, Boonville thrived, perched on bluffs safe from the river’s wrath. It became a significant river port and an enduring commercial center. Other towns, like Arrow Rock, became critical ferry crossings and trading posts, and Columbia and Fayette also owe their early growth to their proximity to the road.

A Crossroads of Humanity: The People of the Road

Boone’s Lick Road was a melting pot of ambition. Farmers seeking fertile land for their crops, merchants looking to establish businesses in new markets, politicians eager to shape the nascent territory, and adventurers seeking untold riches all traversed its dusty path.

Crucially, it’s vital to remember that not all who traveled the road did so willingly. Enslaved African Americans, brought by their owners, were an integral part of this westward migration. Their forced labor cleared land, built homes, and cultivated crops, underpinning the economic development of the region. Their stories, often untold, are a somber but essential part of the road’s complex legacy.

Decline and Enduring Legacy

By the mid-19th century, the era of the great wagon roads began to wane. The advent of the steamboat on the Missouri River offered a faster, more efficient means of transport for goods and people. Then, the iron horse arrived. The railroads, with their speed and capacity, ultimately rendered long-distance wagon roads obsolete.

Sections of Boone’s Lick Road were abandoned, some reverted to nature, while others were absorbed into modern road networks. U.S. Route 40 and Interstate 70, the major east-west corridors across Missouri today, often run parallel to or directly over the original path.

Yet, Boone’s Lick Road endures. Its legacy is etched into the landscape and the collective memory of Missouri. Historical markers dot the route, inviting travelers to pause and reflect on the hardships and triumphs of those who came before. Local historical societies actively work to preserve remaining sections and educate future generations about its significance.

As author William Least Heat-Moon wrote in his book, "Roads to Quoz," "The Boone’s Lick Road was not just a path for movement; it was a place where Missouri began to discover itself, where the raw edges of the frontier were softened into communities, and where the aspirations of a nation took root."

Today, driving along a quiet stretch of Old Boone’s Lick Road, one can almost hear the creak of wagon wheels, the shouts of teamsters, and the dreams whispered into the wind. It stands as a powerful reminder of the determination that shaped a state and propelled a nation westward, a testament to the fact that even a path "paved with salt and peril" can lead to destiny.