The Unfinished Ballot: A Century of Struggle for Native American Voting Rights

The right to vote, a cornerstone of American democracy, has been a hard-won battle for countless groups throughout the nation’s history. For Native Americans, this struggle has been particularly protracted and paradoxical, marked by a complex interplay of tribal sovereignty, federal law, and deeply entrenched state-level discrimination. Even today, a century after gaining nominal citizenship, the fight for equitable access to the ballot box continues in Indian Country.

For much of U.S. history, Native Americans were considered neither citizens nor foreigners in the traditional sense. Instead, they were often classified as "wards of the government" or members of "domestic dependent nations," a legal status that denied them the fundamental rights afforded to other residents, including the right to vote. While treaties signed between tribes and the U.S. government established unique nation-to-nation relationships, they rarely conferred citizenship or voting rights on tribal members. In fact, many treaties stipulated that tribal members would be governed by their own laws, inadvertently reinforcing their exclusion from the American political system.

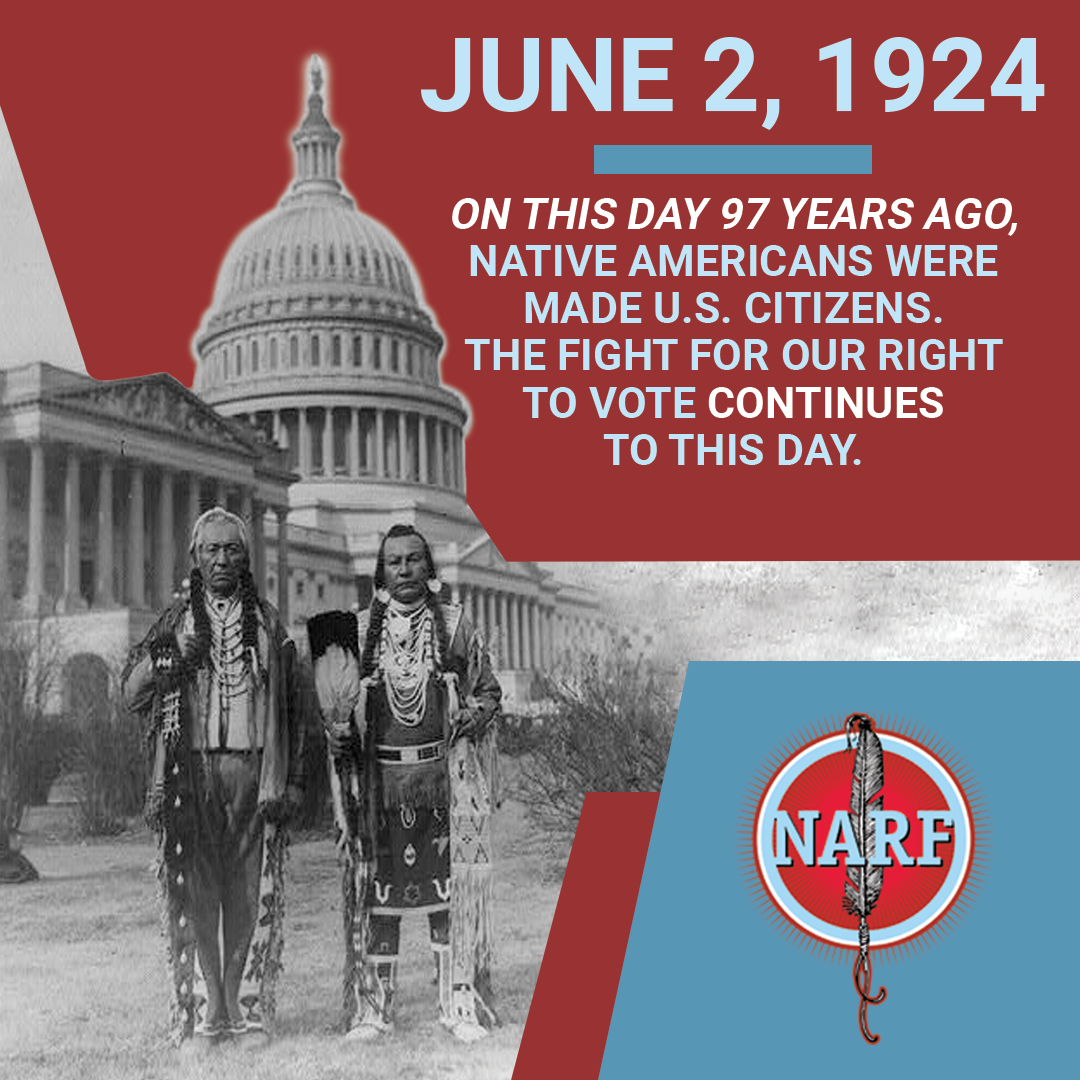

1924: A Bittersweet Victory

The first major turning point arrived on June 2, 1924, with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act, also known as the Snyder Act. This federal law declared all non-citizen Native Americans born in the United States to be U.S. citizens. For many, it seemed like a monumental step towards inclusion. President Calvin Coolidge signed the bill, ostensibly granting Native Americans the same rights as other citizens.

However, the reality was far more complex. While the Snyder Act conferred federal citizenship, it did not automatically guarantee the right to vote. States retained significant power to regulate suffrage, and many quickly erected barriers specifically targeting Native Americans. "The 1924 act was a landmark, but it was far from a panacea," explains historian Dr. Sarah M. Johnson, specializing in Native American legal history. "It was a federal declaration, but the states were where the real fight lay."

State-Sanctioned Disenfranchisement

Following 1924, Native Americans faced a litany of discriminatory state laws and practices designed to prevent them from casting ballots. These included:

- "Wardship" Clauses: Many states argued that Native Americans living on reservations were still under federal "wardship" and thus not truly independent citizens capable of voting. Arizona and New Mexico were particularly egregious in this regard.

- Literacy Tests: Ostensibly neutral, these tests were often administered selectively and used to disqualify Native Americans, particularly those whose primary language was not English or who had limited access to formal education due to federal assimilation policies.

- Poll Taxes: Requiring payment to vote, these taxes disproportionately affected Native Americans, who often lived in poverty due to federal land policies and economic marginalization.

- Residency Requirements: Some states manipulated residency rules, arguing that living on a reservation did not constitute residency within a state or county for voting purposes.

- Exclusion from "Civilized" Society: In some states, particularly in the South, Native Americans were grouped with other racial minorities and subjected to Jim Crow-era laws that enforced segregation and denied voting rights. Maine, for instance, did not fully grant voting rights to its Native American population until 1954, arguing they were "wards of the state" and not subject to state jurisdiction while living on tribal lands. Utah followed suit in 1956.

The hypocrisy of the situation became glaringly apparent during World War II. Thousands of Native American men and women served valiantly in the U.S. armed forces, fighting for democracy abroad, only to return home to find their own democratic rights denied. The famed Navajo Code Talkers, whose unbreakable code was vital to Allied victory, were among those who might have faced barriers to voting in their home states. This stark contrast between service and disenfranchisement fueled growing activism within Native communities.

Landmark Victories and the VRA’s Impact

The post-WWII era saw significant legal challenges to state-level discrimination. In 1948, two landmark cases finally broke down the most overt barriers. In Harrison v. Laveen, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans could not be denied the right to vote solely because they were "wards of the government" or lived on reservations. The court found that such an interpretation was discriminatory and violated the 15th Amendment. In the same year, the New Mexico Supreme Court, in Trujillo v. Garley, similarly struck down its state’s constitutional provision that denied voting rights to "Indians not taxed," effectively opening the ballot box for Native Americans in the state.

While these victories were crucial, they did not eliminate all obstacles. It wasn’t until the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 that a comprehensive federal framework emerged to protect minority voting rights. The VRA, primarily aimed at dismantling Jim Crow laws in the South, also had a profound impact on Native American communities. Section 2, which prohibited voting practices that discriminate on the basis of race or color, became a powerful tool. Section 5, which required certain jurisdictions with histories of discrimination to pre-clear any changes to their voting laws with the Department of Justice, provided an essential safeguard against new discriminatory tactics.

The VRA led to increased voter registration and turnout in many Native communities. It helped to challenge practices like at-large elections, which diluted Native American voting strength, and it mandated language assistance in areas with significant populations of non-English speakers, a critical provision for tribes with members who primarily spoke their ancestral languages.

The Ongoing Fight: Unique Challenges in the Modern Era

Despite the VRA, the struggle for Native American voting rights is far from over. The unique circumstances of tribal sovereignty, geography, and socio-economic factors present distinct challenges that often go unaddressed by broader voting rights legislation.

- Geographic Isolation and Infrastructure: Many reservations are vast, remote, and lack basic infrastructure. Polling places can be dozens, even hundreds, of miles away, with no public transportation. This makes in-person voting a significant burden.

- Lack of Traditional Addresses: Many homes on reservations do not have street addresses, instead using P.O. boxes or descriptive land markers. This can create issues with voter registration forms that require a physical address, or with new voter ID laws that demand proof of residence with a street address. In 2018, North Dakota passed a strict voter ID law that disproportionately affected Native Americans, many of whom did not have IDs with street addresses. A federal judge eventually ruled that tribal IDs could be used, but the initial law created immense confusion and suppression.

- Mail Service Limitations: For communities without reliable mail delivery, absentee voting can be impractical or impossible.

- Language Barriers: While the VRA requires language assistance, implementation can be inconsistent. Many elderly tribal members may primarily speak their native language, making English-only ballots and instructions a barrier.

- Voter ID Laws: Increasingly restrictive voter ID laws, often championed by states for "election integrity," disproportionately impact Native Americans who may lack the specific forms of ID required due to poverty, lack of access to government services, or the aforementioned address issues.

- Gerrymandering and Redistricting: Native American communities are often targets of gerrymandering, where district lines are drawn to dilute their political power, particularly when they constitute a significant minority within a larger, predominantly non-Native area.

- Polling Place Closures and Cuts: Remote polling places on reservations are often the first to be closed or have their hours reduced, citing cost or low turnout, further exacerbating access issues.

- Cultural and Historical Mistrust: Generations of broken treaties, forced assimilation, and discrimination have fostered a deep-seated mistrust of federal and state governments. This historical trauma can manifest as cynicism towards the political process, making voter engagement more challenging.

The Power of the Native Vote

Despite these hurdles, Native American communities are increasingly asserting their electoral power. Organizations like the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), Four Directions, and tribal voting rights groups are actively working to overcome these barriers through litigation, voter education, registration drives, and advocacy. They push for satellite polling places on reservations, acceptance of tribal IDs, and fair redistricting.

"Every vote cast by a Native American is not just a personal choice; it’s an assertion of sovereignty, a reclamation of voice, and a step towards a more equitable future for our communities," says Allie Young, founder of Protect the Sacred, a Navajo Nation grassroots organization. "Our ancestors fought for our very existence, and voting is a continuation of that fight for self-determination."

The Native American vote can be decisive in swing states and congressional districts, especially in states like Arizona, New Mexico, Montana, North Dakota, and Alaska. As tribal populations grow and organizing efforts strengthen, their collective voice in the political arena becomes louder and more impactful, shaping outcomes in local, state, and national elections.

The journey for Native American voting rights has been long and arduous, marked by both hard-won victories and persistent challenges. From the federal declaration of citizenship in 1924 to the ongoing battles for equitable access in the 21st century, the story is one of resilience, determination, and the enduring pursuit of true democratic participation. The ballot box remains a crucial battlefield in the ongoing struggle for Native American self-determination and justice within the United States.