Echoes of a Forgotten War: Native Americans in the American Civil War

The American Civil War, often portrayed as a conflict solely between North and South, white against white, was a far more complex tapestry woven with diverse threads of loyalty, desperation, and survival. Among the most overlooked, yet profoundly impacted, participants were the Native American nations, caught in the crosscurrents of a war that was not inherently theirs, yet irrevocably shaped their destinies. From the dense forests of the Indian Territory to the battlefields of Missouri, thousands of Native Americans fought, bled, and died, many of them in battles against each other, as ancient tribal rivalries and pragmatic alliances dictated their choices.

At the war’s outbreak in 1861, the situation for Native American tribes, particularly the "Five Civilized Tribes" (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole) residing in the Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), was precarious. Decades earlier, under the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the subsequent forced migration known as the Trail of Tears, these nations had been forcibly relocated from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States. They had painstakingly rebuilt their societies, establishing written constitutions, schools, and prosperous farms, often including the institution of slavery, mirroring their Southern neighbours.

Their geographical proximity to the Confederacy, coupled with long-standing grievances against the U.S. federal government for broken treaties and the trauma of removal, made an alliance with the nascent Confederate States of America seem, to many, a pragmatic choice. The Confederacy, keen to secure its western flank and recruit additional manpower, aggressively courted these tribes. Albert Pike, a prominent lawyer and politician, was appointed Confederate Commissioner to the Indian Nations, promising autonomy, protection from federal interference, and financial annuities that the Union had ceased paying.

For tribes like the Choctaw and Chickasaw, who had strong cultural and economic ties to the South, and whose leaders often owned enslaved people, joining the Confederacy was a relatively straightforward decision. They quickly signed treaties and raised regiments. The Cherokee Nation, however, was deeply divided. Principal Chief John Ross, who had long advocated for neutrality, initially resisted Confederate overtures, hoping to avoid entanglement in a "white man’s war." But pressure mounted. Union troops withdrew from the territory, leaving the Cherokee vulnerable. The surrounding Confederate states were heavily armed, and pro-Confederate factions within the Cherokee, led by Elias C. Boudinot and Stand Watie, pushed for alliance.

Stand Watie, a veteran of the Cherokee Removal and a bitter rival of John Ross, proved to be a formidable Confederate leader. He quickly raised the First Cherokee Mounted Rifles, which would become one of the most effective cavalry units in the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department. Watie, a master of guerrilla warfare, would be the last Confederate general to surrender, laying down his arms nearly two months after Robert E. Lee at Appomattox. His loyalty to the Confederacy was unwavering, fueled by a deep distrust of the U.S. government and a belief that the South offered a better future for his people.

Yet, not all Native Americans sided with the Confederacy. Many, particularly the Creek under the leadership of Opothleyahola, remained staunchly loyal to the Union, viewing the federal government, despite its past betrayals, as the legitimate authority. Opothleyahola, a revered Creek chief, refused to sign a treaty with the Confederacy, declaring, "We are for the Union. We have our treaties with the United States. We will stand by them." He rallied thousands of Union-loyal Creeks, Seminoles, and Cherokees, along with some African Americans, on a desperate exodus north towards Kansas in the winter of 1861, hoping to reach Union lines. This perilous journey, known as the "Flight of the Loyal Refugees," was marked by fierce skirmishes with Confederate and pro-Confederate Native American forces, including Watie’s Cherokees, leading to significant casualties from battle, starvation, and exposure.

The Civil War in the Indian Territory was, therefore, not just a clash of Union and Confederate ideologies, but a bitter internal struggle within and between Native nations. Families were torn apart, traditional loyalties tested, and ancient feuds reignited. The conflict was particularly devastating because it pitted neighbours and even relatives against each other. The Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas (March 1862) saw Native American troops fighting on both sides, with Cherokee regiments under Watie playing a significant role for the Confederates.

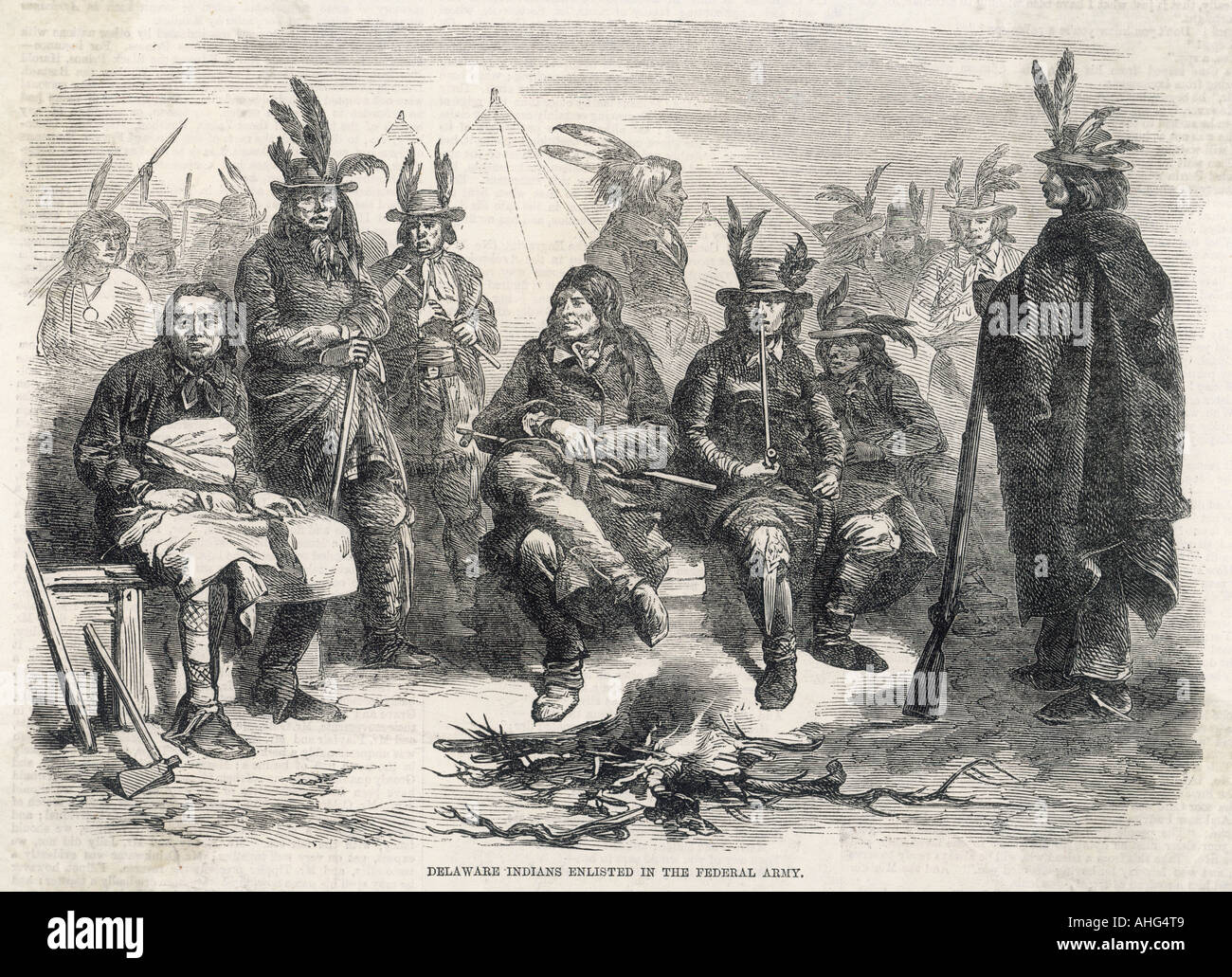

The Indian Home Guard regiments, composed of Union-loyal Native Americans, were eventually formed and played a crucial role in reasserting Union control over parts of the Indian Territory. These troops, often poorly equipped and facing discrimination from some white Union officers, fought with remarkable courage. The Battle of Honey Springs (July 1863), often called the "Gettysburg of the West," was the largest Civil War engagement in the Indian Territory and involved a significant number of Native American soldiers. Union forces, including the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry and various Indian Home Guard regiments, decisively defeated a Confederate force that included Stand Watie’s Cherokees, marking a turning point for Union control in the region.

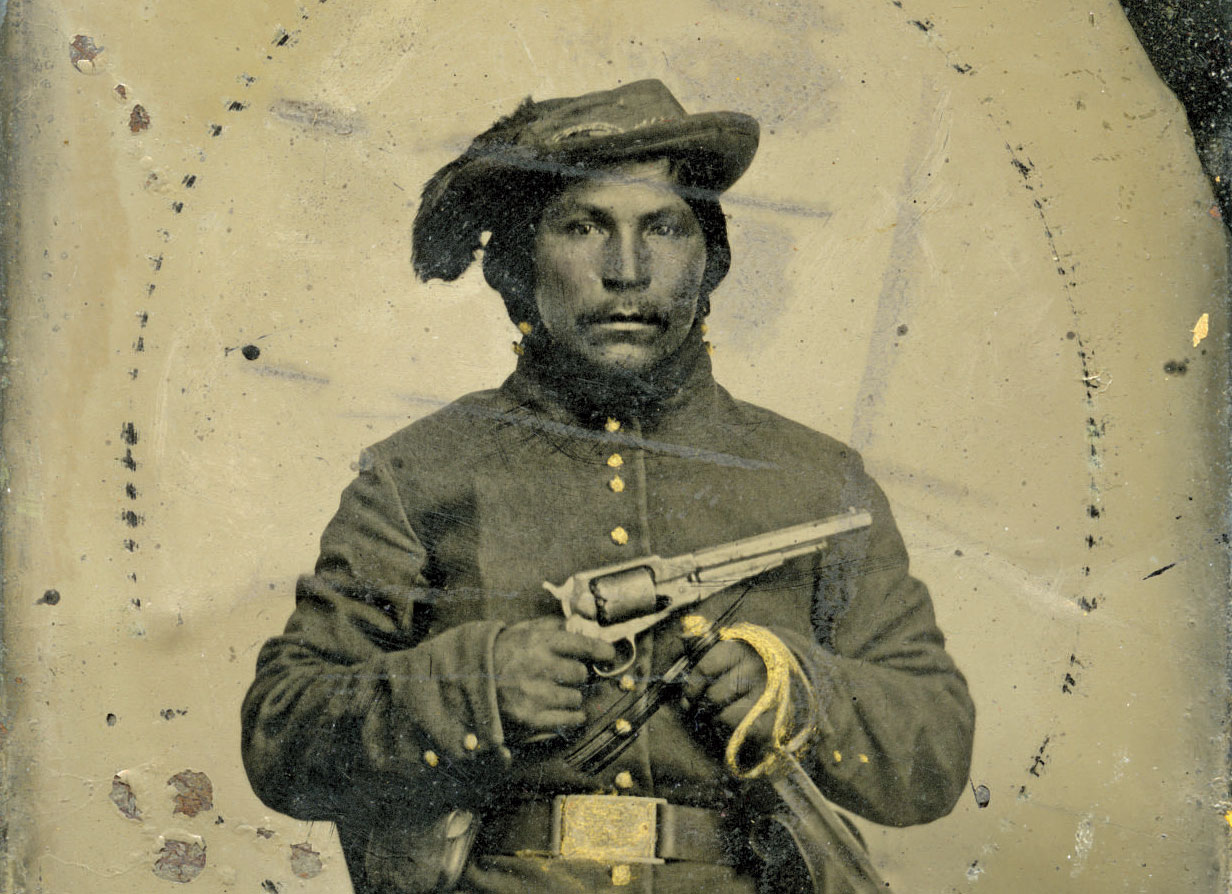

Beyond the Indian Territory, individual Native Americans served in various capacities within both Union and Confederate armies. Perhaps the most prominent was Ely S. Parker, a Seneca Indian who rose to the rank of Brigadier General in the Union Army and served as Ulysses S. Grant’s military secretary. A trained engineer and lawyer, Parker famously drafted the surrender terms signed by Lee at Appomattox Court House. When Lee reportedly remarked, "I am glad to see one real American here," Parker is said to have replied, "We are all Americans." Parker’s career exemplified the potential for Native Americans to achieve high office and contribute significantly, even while their communities faced immense hardship.

The impact of the war on Native American nations was catastrophic. Indian Territory became a ravaged land, with farms destroyed, homes burned, and communities shattered. Estimates suggest that the Cherokees lost a quarter of their population, and the Creeks and Seminoles suffered even greater proportional losses. The war not only brought physical devastation but also deepened existing divisions and created new ones that would linger for generations.

The aftermath of the war was equally harsh. Despite the fact that many tribes had remained loyal to the Union, and even those who sided with the Confederacy had often done so under duress or perceived necessity, the U.S. government treated all tribes in the Indian Territory as defeated enemies. New treaties were imposed, leading to further land cessions and the erosion of tribal sovereignty. The Five Civilized Tribes were forced to cede vast tracts of their lands, some of which were used to resettle other tribes from the Plains, leading to new conflicts.

The story of Native Americans in the Civil War is a stark reminder of the complex and often tragic choices faced by marginalized communities during times of national upheaval. They fought not for abstract ideals of Union or Confederacy, but for the survival of their people, the protection of their lands, and the preservation of their way of life. Their participation highlights the profound irony that while white Americans battled over the future of the nation, Native Americans, the original inhabitants, found their own precarious existence further jeopardized. Their sacrifices, contributions, and the immense suffering they endured remain a vital, yet frequently unacknowledged, chapter in the narrative of the American Civil War, deserving of a prominent place in our historical consciousness.