The Sovereign’s Dilemma: Navigating the Labyrinth of Tribal Law Enforcement Jurisdiction

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

The dust-laced wind whips across the vast, open plains of the reservation, a stark reminder of the freedom and challenge that define life in Indian Country. But beneath the wide-open skies, a complex and often bewildering legal landscape dictates who has the authority to uphold justice. For tribal law enforcement officers, every siren call, every investigation, every arrest is shadowed by a fundamental question: Do we have jurisdiction?

This question, seemingly simple, unravels into a tangled web of historical treaties, federal laws, Supreme Court decisions, and deeply ingrained sovereignty issues that often leave victims vulnerable, perpetrators unpunished, and tribal communities feeling like second-class citizens in their own homelands.

"It’s like trying to solve a puzzle where half the pieces are missing and the other half belong to a different box entirely," says Chief John Red Horse, a veteran tribal police officer with the fictional Lakota Nations Police Department. "We know our communities, our people. We’re on the ground. But too often, our hands are tied by laws made far away, without our input, and with little understanding of our realities."

A Legacy of Eroded Sovereignty: The Oliphant Decision

To understand the current jurisdictional quagmire, one must look to the past. Before the mid-20th century, tribal nations largely exercised inherent criminal jurisdiction over all persons within their territories, regardless of race. This was a core tenet of their sovereignty. However, a series of federal actions and court rulings chipped away at this authority.

The most impactful of these was the 1978 Supreme Court decision in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe. In a ruling that shocked tribal nations, the Court held that Indian tribal courts do not have inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. This decision created a massive jurisdictional void. If a non-Native individual committed a crime, even a violent one, on tribal land, tribal law enforcement had no authority to arrest or prosecute them. The case stemmed from a challenge by a non-Indian charged with assaulting a tribal officer and resisting arrest on the Port Madison Indian Reservation in Washington State.

"Oliphant was a gut punch," explains Dr. Sarah Many Rivers, a legal scholar specializing in Native American law. "It fundamentally undermined tribal sovereignty and created a safe haven for non-Native criminals on reservations. They knew tribal police couldn’t touch them, and federal or state agencies were often too far away, too understaffed, or too uninterested to respond effectively."

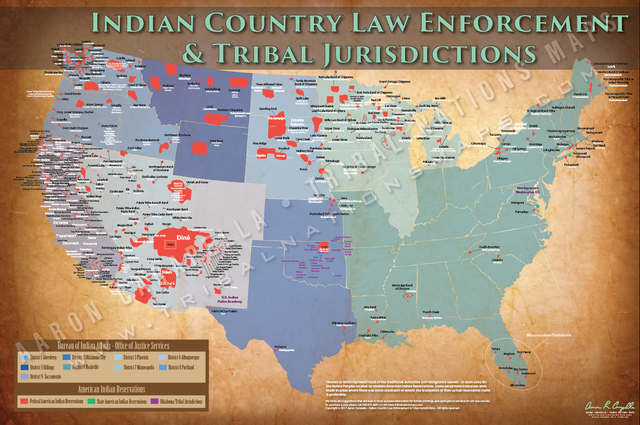

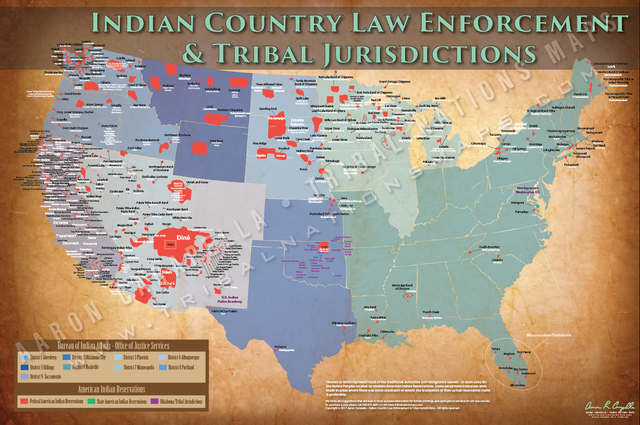

Following Oliphant, crimes committed by non-Indians in Indian Country could only be prosecuted by the federal government, or in some cases, by states under specific agreements like Public Law 280 (which granted certain states broad criminal and civil jurisdiction over reservations). This placed an enormous burden on federal prosecutors and the FBI, agencies often overwhelmed and under-resourced for the sheer volume of cases emerging from hundreds of reservations across the country.

The Tangled Web: Who Has Authority?

Today, the jurisdictional landscape in Indian Country is a complex matrix depending on:

- Who committed the crime (Indian or Non-Indian)?

- Who was the victim (Indian or Non-Indian)?

- Where did the crime occur (Indian Country, fee land within a reservation, or off-reservation)?

- What type of crime was it (e.g., a major felony vs. a minor misdemeanor)?

- Is the state a "PL 280" state?

- Crimes committed by Indians against Indians in Indian Country: Tribal courts have jurisdiction over misdemeanors. For "Major Crimes" (a list of offenses like murder, rape, arson, etc., defined by the federal Major Crimes Act of 1885), federal courts have exclusive jurisdiction.

- Crimes committed by Indians against non-Indians in Indian Country: Generally, federal courts have jurisdiction.

- Crimes committed by Non-Indians in Indian Country: As per Oliphant, tribal courts have NO criminal jurisdiction. Federal courts have jurisdiction, but often only for specific crimes or if the crime impacts an Indian or Indian property. State courts may have jurisdiction in PL 280 states or if the crime occurred on fee land (privately owned land within reservation boundaries).

This intricate web means that an assault on a reservation might be handled by tribal police, the FBI, the local sheriff’s department, or a combination, depending on the race of those involved and the specific location. The result is often confusion, delayed responses, and a frustrating lack of justice for victims.

The Human Cost: VAWA and MMIP

The most harrowing consequences of this jurisdictional maze are seen in the rates of violence against Indigenous women and the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP). Indigenous women face murder rates more than ten times the national average in some areas, and more than four in five Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime.

For decades, the Oliphant ruling meant that non-Native perpetrators—who commit a disproportionate amount of violence against Native women—could often escape justice if the crime occurred on tribal land. Tribal police could not arrest them, and federal authorities often declined to prosecute due to resource constraints or a perceived lack of severity for certain crimes.

"Before 2013, if a non-Native perpetrator committed domestic violence on our reservation, our hands were tied," recalls Maria Strong Heart, a tribal advocate for survivors of violence. "He could walk away, knowing our police couldn’t touch him. Our women were left without protection, without recourse. It was a terrifying reality."

Significant progress was made with the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) in 2013. This landmark legislation partially restored tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indian perpetrators of domestic violence who have a significant tie to the tribe (e.g., residing in Indian Country or being in a dating relationship with a tribal member). This was a major victory, allowing tribes to prosecute these specific crimes in their own courts, closing a critical gap left by Oliphant.

Further strides were made with the VAWA 2022 reauthorization, which expanded tribal jurisdiction to include non-Native perpetrators of sexual assault, child abuse, stalking, trafficking, and assault on tribal law enforcement officers in Indian Country. This expansion recognized the severe and interconnected nature of these crimes and provided more tools for tribal justice systems.

While VAWA’s reauthorizations are crucial steps, they are not a complete solution. They don’t restore full criminal jurisdiction over all crimes or all non-Indian perpetrators. The jurisdictional gaps contribute directly to the MMIP crisis, where cases often fall through the cracks between tribal, federal, and state agencies, leading to delayed investigations and an appalling lack of data.

Challenges Beyond Jurisdiction: Resources and Relationships

Even where jurisdiction is clear, tribal law enforcement faces immense challenges:

- Underfunding: Tribal police departments are chronically underfunded compared to their state and local counterparts. This leads to understaffing, outdated equipment, and lower salaries, making it difficult to recruit and retain officers. "We cover vast territories with a fraction of the officers and resources of a typical county sheriff’s department," says Chief Red Horse. "It’s a constant struggle."

- Training and Equipment: Access to advanced training, forensic tools, and technology is often limited, hindering effective investigations.

- Inter-Agency Cooperation: Despite federal mandates for collaboration, historical mistrust, communication breakdowns, and differing protocols can impede effective partnerships between tribal, federal, and state agencies. Data sharing, especially regarding criminal databases, remains a significant hurdle.

"We need genuine partnerships, not just lip service," states Sarah Jensen, an Assistant U.S. Attorney for the District of Montana, who frequently works on cases in Indian Country. "When tribal, federal, and state agencies truly collaborate, sharing intelligence and resources, we see better outcomes for victims and stronger communities."

Moving Forward: Pathways to Justice

Despite the formidable obstacles, there are ongoing efforts and proposed solutions aimed at strengthening tribal justice systems and ensuring safety in Indian Country:

- Restoring Full Tribal Criminal Jurisdiction: Many tribal leaders and advocates argue for a complete legislative restoration of inherent tribal criminal jurisdiction over all persons and crimes within their territories, reversing the Oliphant decision entirely. This would empower tribes to fully protect their communities as sovereign nations.

- Enhanced Federal Funding and Resources: Increased and sustained federal funding for tribal law enforcement, courts, and victim services is critical to build capacity and address the disparities.

- Mandatory Data Sharing and Collaboration: Legislation or policy changes that mandate seamless data sharing and require inter-agency cooperation protocols could significantly improve response times and case resolution.

- Cross-Deputization and Mutual Aid Agreements: These agreements allow tribal officers to enforce state or federal law (and vice-versa) in specific circumstances, bridging some jurisdictional gaps. While effective, they are often piecemeal and dependent on the willingness of individual agencies.

- Strengthening Tribal Courts: Investing in tribal court infrastructure, training for judges and prosecutors, and developing culturally relevant restorative justice programs can enhance tribal nations’ ability to administer justice effectively.

The journey toward full justice and safety in Indian Country is long and arduous. It requires a fundamental shift in understanding and respect for tribal sovereignty, a commitment to equitable resource allocation, and sustained collaboration across all levels of government.

"Justice delayed is justice denied, and for many in Indian Country, justice is often outright denied due to these complex jurisdictional issues," concludes Dr. Many Rivers. "The path forward is clear: recognize tribal nations as full partners, empower their justice systems, and finally ensure that all people, regardless of where they live, are equally protected by the law."

The wind still blows across the plains, but now, perhaps, there is a growing hope that the intricate puzzle of jurisdiction might one day be solved, allowing tribal nations to fully exercise their inherent right to protect and serve their own.