The Unfought War: How a Nation Nearly Divided Over Deseret

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH TERRITITORY – In the annals of American history, few conflicts are as peculiar, as fraught with misunderstanding, and as ultimately bloodless between the primary combatants as the Utah War of 1857-1858. Often dubbed "the war without a battle," this remarkable standoff pitted the burgeoning federal authority of the United States against the fiercely independent and deeply religious settlers of the Utah Territory, primarily members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, commonly known as Mormons. It was a clash of cultures, a test of religious freedom, and a tense prelude to the nation’s even greater unraveling a few years later.

At its heart, the Utah War was a collision between an expansionist American government, increasingly sensitive to challenges to its authority, and a unique religious community that had, for decades, faced persecution, forced displacement, and a profound desire to govern itself in its isolated mountain refuge.

A People Forged in Fire: The Mormon Exodus

The story of the Utah War cannot begin without understanding the arduous journey of the Latter-day Saints. Driven from Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois by mob violence and governmental indifference, their westward trek under the leadership of Brigham Young was an epic of faith and endurance. In 1847, they arrived in the desolate Salt Lake Valley, a place so remote they hoped it would offer the peace and autonomy they craved. They called their proposed state "Deseret," a word from the Book of Mormon meaning "honeybee," symbolizing industry and cooperation.

Through incredible ingenuity and collective effort, they transformed the arid landscape into a blossoming oasis. By the mid-1850s, Salt Lake City was a thriving hub, attracting converts from across the globe. When the Mexican-American War concluded, the Salt Lake Valley became part of U.S. territory, and in 1850, the Utah Territory was formally organized. Brigham Young, the charismatic and authoritarian leader, was appointed its first territorial governor by President Millard Fillmore.

However, the very practices that bound the Mormon community together also sowed the seeds of federal distrust. Their system of communal economic ventures, their unified political and religious leadership (a "theocracy" in the eyes of many outsiders), and, most controversially, their practice of plural marriage (polygamy), were seen as antithetical to American republican ideals. Polygamy, in particular, was condemned across the nation as a "relic of barbarism," a moral affront that became a rallying cry for those who viewed the Mormons with suspicion and hostility.

The Spark: Buchanan’s Miscalculation

By 1857, reports reaching Washington, D.C., painted a grim, often exaggerated, picture of affairs in Utah. Federal judges and officials, many of whom found the insular Mormon society alien and challenging, returned East with tales of Mormon defiance, obstruction of justice, and a general disregard for federal law. They accused Brigham Young of ruling with an iron fist, preventing non-Mormons from settling, and even inciting rebellion.

President James Buchanan, a Democrat only recently inaugurated, was under immense pressure to assert federal authority. He was keen to project strength and unity in a nation increasingly fractured by the slavery debate. A strong response to the "Mormon rebellion" in far-off Utah seemed like a low-risk way to demonstrate federal resolve.

Without a formal investigation, and largely relying on biased accounts, Buchanan made a fateful decision: he would replace Brigham Young as governor with a non-Mormon, Alfred Cumming of Georgia, and send a substantial portion of the U.S. Army to escort him and enforce federal law. The "Utah Expedition," a force of some 2,500 soldiers, led by Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, was ordered to march west.

Buchanan’s proclamation, issued in the summer of 1857, declared the Utah Territory in a state of "rebellion," accusing the Mormons of "treasonable acts." This decision, based on flimsy evidence and without due process, ignited the conflict.

Mormon Response: "We Will Be Driven No More"

News of the approaching army reached Utah in July 1857, via an overland mail carrier. Brigham Young and the Mormon leadership viewed it as another act of persecution, a continuation of the violence that had driven them from their homes repeatedly. This time, however, they were prepared to stand their ground.

"We have been driven five times from our homes," Young famously declared, "and we shall be driven no more." He immediately declared martial law, mobilized the Nauvoo Legion (the territorial militia), and adopted a strategy of non-violent resistance coupled with a scorched-earth policy.

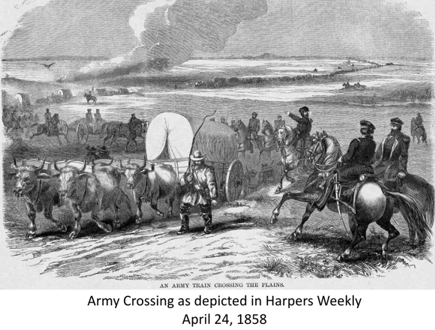

The Mormons had no intention of engaging the U.S. Army in open battle, knowing they were vastly outmatched. Instead, their strategy focused on harassment, delaying tactics, and making the territory inhospitable. Mormon militia units, under the command of figures like Major Lot Smith, conducted daring raids on army supply trains, burning wagons, driving off livestock, and destroying forage.

"We felt it was our duty to do all we could to delay their march," Smith later recounted, describing how his men burned supply trains and stampeded army cattle. "It was a war of attrition, not of bullets." These actions, though not resulting in direct combat fatalities, effectively crippled the army’s logistical capabilities and bogged them down in the vast, unforgiving Western landscape.

Tragedy in the Meadows: A Dark Stain

Amidst the heightened tensions and war hysteria, a horrific tragedy unfolded that would forever stain the historical narrative of the Utah War: the Mountain Meadows Massacre. In September 1857, a wagon train of emigrants from Arkansas, bound for California, was attacked by a local Mormon militia and Native American allies in southern Utah. After a siege, the emigrants surrendered under a flag of truce, only to be systematically slaughtered, with only 17 young children spared.

While not a direct order from Brigham Young or a central act of the "war" itself, the massacre was a terrible consequence of the atmosphere of fear, distrust, and paranoia created by the approaching army. The emigrants, some of whom were perceived as having participated in anti-Mormon violence in Missouri, became tragic scapegoats. The massacre, which was eventually prosecuted years later, deeply shocked the nation and further solidified negative perceptions of the Mormons, even as the "war" itself was winding down.

The Unlikely Peacemakers

As winter approached, the U.S. Army, battered by Mormon raids and the harsh conditions, was forced to halt its advance and establish winter quarters at Camp Scott (near present-day Fort Bridger, Wyoming). Their supplies were low, and morale was flagging. The "rebellion" they had expected to crush quickly had proven to be a tenacious, elusive foe.

It was at this critical juncture that diplomacy, rather than direct confrontation, began to prevail. President Buchanan, facing mounting criticism for his handling of the situation, dispatched a peace commission to Utah. Crucially, a private citizen, Colonel Thomas L. Kane, a non-Mormon and a long-time friend of the Latter-day Saints, played an extraordinary, unofficial role.

Kane, traveling secretly and at his own expense, arrived in Utah in February 1858. He was a trusted intermediary, able to speak frankly with Brigham Young and later with Governor Cumming and Colonel Johnston. His efforts were instrumental in bridging the vast chasm of misunderstanding.

Upon his arrival, Governor Alfred Cumming, the new federal appointee, proved to be another vital figure in the peaceful resolution. Unlike his predecessors, Cumming was diplomatic and determined to fulfill his duties peacefully. He entered Salt Lake City in April 1858, unaccompanied by the military, relying on Kane’s groundwork and his own courage. Brigham Young, demonstrating remarkable political acumen, welcomed Cumming and formally relinquished the governorship, acknowledging federal authority.

The "Move South" and a Peaceful Resolution

Even as Cumming took office, a peculiar and poignant event unfolded: the "move south." Fearing continued hostilities, Brigham Young orchestrated a mass exodus of the Mormon population from Salt Lake City and northern settlements. Homes were boarded up, furniture was buried, and the entire population prepared to torch their homes if the army proved hostile. This act demonstrated the Mormons’ unwavering resolve and their willingness to sacrifice everything rather than submit to what they perceived as unjust coercion.

In June 1858, the U.S. Army, now under the command of Colonel Johnston, finally marched through a deserted Salt Lake City. They passed through the silent streets and continued another 30 miles south to establish Camp Floyd (later Fort Crittenden), a large military post that would remain a federal presence in the territory for several years. The army made no attempt to interfere with the returning Mormon settlers or their property. President Buchanan, in turn, issued a general pardon to all Mormons for any acts of "rebellion."

Legacy: A Precedent and Lingering Tensions

The Utah War officially ended without a single major engagement between the U.S. Army and the Mormon militia. While casualties were minimal (mostly due to skirmishes over supplies and accidents), the cost was immense: millions of dollars for the federal government, a significant disruption to Utah’s development, and a deep scar of mistrust.

The war set important precedents. It affirmed federal authority over the territories, even in the face of strong local resistance, yet it also demonstrated the limits of military force when confronting a determined, unified population. For the Mormons, it solidified their identity as a people who would defend their faith and autonomy at all costs.

Despite the peaceful resolution, tensions lingered. The presence of Camp Floyd, with its thousands of soldiers, continued to be a source of friction. The issue of polygamy remained a federal obsession, leading to decades of legal battles and eventually, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints officially abandoning the practice in 1890, a crucial step toward Utah achieving statehood in 1896.

The Utah War, though often overshadowed by the larger conflicts of American history, stands as a unique chapter – a test of federal power, religious freedom, and the capacity for peaceful resolution in the face of profound misunderstanding. It reminds us that even when drums of war beat loudest, the quiet, persistent efforts of diplomacy and empathy can often avert catastrophe, leaving an "unfought war" as a powerful, albeit peculiar, legacy.