The Artery of Empire: Tracing the Fort Riley Fort Kearny Road

The American West, a landscape etched with the ghosts of forgotten trails and the whispers of a bygone era, holds countless stories of ambition, hardship, and the relentless march of a nation. Among these historical arteries, less celebrated but profoundly significant, lies the Fort Riley Fort Kearny Road. More than just a path connecting two pivotal military outposts, this approximately 200-mile stretch across the vast prairies of Kansas and Nebraska was a vital lifeline, a conduit of manifest destiny, and a silent witness to the epic transformation of a continent.

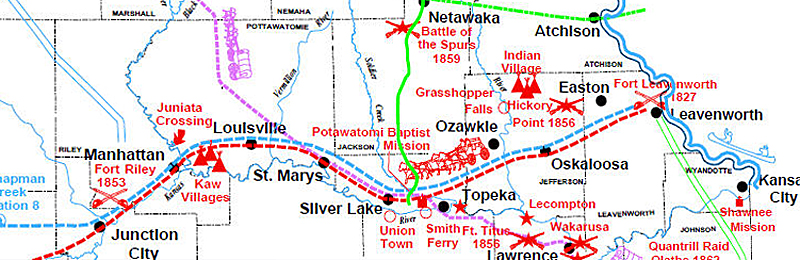

In the mid-19th century, as the siren call of gold in California and the promise of fertile lands in Oregon drew hundreds of thousands westward, the need for secure, reliable routes became paramount. The established trails – the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe – were well-trodden but fraught with danger. Disease, natural perils, and conflicts with Native American tribes were constant threats. It was against this backdrop that the strategic importance of military forts, acting as beacons of safety and supply depots, became undeniable. Fort Kearny in Nebraska, established in 1848, was the first military post built specifically to protect emigrants on the Oregon Trail. Further south, in Kansas, Fort Riley was founded in 1853, primarily to protect the Santa Fe Trail and serve as a base for operations against hostile tribes.

The gap between these two crucial bastions, however, was a significant logistical challenge. Supplies, mail, and military personnel often had to traverse circuitous and insecure routes. The vision of a direct road connecting Fort Riley to Fort Kearny emerged from this necessity – a dedicated military road that would shorten travel times, enhance communication, and provide a more secure corridor for both military movements and, indirectly, civilian emigrants.

A Lifeline Forged in Necessity

The construction and maintenance of the Fort Riley Fort Kearny Road were not formal, massive engineering projects in the modern sense. Rather, it evolved organically from repeated military expeditions, supply trains, and the passage of troops. The earliest significant movements along this general corridor date back to the 1850s. Military engineers and surveying parties, often accompanied by troops for protection, would mark the most practical routes, identifying water sources, favorable river crossings, and suitable camping grounds. These initial paths were then widened and maintained through the constant passage of wagons and cavalry.

The road’s primary purpose was military. It facilitated the rapid deployment of troops, particularly cavalry, to address conflicts with Native American tribes or to escort vulnerable wagon trains. Ammunition, provisions, medical supplies, and mail flowed in both directions, sustaining the garrisons and enabling their operations. For instance, when troops from Fort Riley were needed further north, or when Fort Kearny required reinforcements or specific supplies from the larger logistical hub at Fort Leavenworth (via Fort Riley), this road became the most efficient means of transport.

Life on the military road was arduous. Soldiers tasked with guarding supply trains or patrolling the route faced extreme weather, from scorching summer heat and parched earth to brutal winter blizzards. They contended with the constant threat of ambush, the isolation of the vast prairie, and the ever-present danger of disease. Yet, their presence was a testament to the nation’s commitment to westward expansion and its determination to control the frontier.

The Emigrant’s Unofficial Artery

While primarily a military thoroughfare, the Fort Riley Fort Kearny Road quickly became an unofficial, yet highly valued, bypass and connection for emigrants. Many heading west, especially those starting from points in Missouri or eastern Kansas, found it advantageous to travel to Fort Riley first. From there, they could access military protection, purchase last-minute supplies, or gain valuable intelligence about conditions further west. The road then offered a direct link to the established Oregon Trail at Fort Kearny, allowing them to join the main westward flow.

For these pioneers, the road offered a semblance of security in a wilderness often perceived as hostile. The very existence of a military-maintained route suggested a safer passage. Wagon trains, often numbering dozens of families, would brave the journey, their covered wagons creaking under the weight of their possessions and their dreams. The landscape they traversed was one of sweeping grasslands, occasional timbered creek bottoms, and wide-open skies – beautiful yet unforgiving.

The hardships faced by these emigrants were immense. Cholera, a virulent disease, swept through wagon trains, claiming lives with horrifying speed. Accidents – overturned wagons, stampeding livestock, accidental gunshots – were common. The psychological toll of the journey, the constant fear, the monotony, and the loss of loved ones, was profound. Yet, the promise of a new life, of land and opportunity, drove them relentlessly forward.

Quotes from the Trail

While specific diarists or letters directly referencing "Fort Riley Fort Kearny Road" by name are rare (as it was often just part of a larger journey), the experiences along this type of military-civilian shared route are well-documented. Emigrants often expressed their relief upon reaching a fort.

One unnamed diarist, upon reaching a fort on the plains, wrote, "It was a great relief to see the flag waving in the distance. We knew then we had found a place of safety, if only for a night." This sentiment encapsulates the forts’ role as vital oases.

Another pioneer, reflecting on the dangers, stated, "The journey was fraught with peril, but the presence of the soldiers, though distant, gave us courage to press on." This speaks to the indirect yet powerful psychological comfort provided by military roads.

The Intertwined Destinies

The relationship between the military and the emigrants on this road was symbiotic. The military relied on the emigrant flow, in part, as a justification for their presence and funding, and their actions directly impacted the safety of the civilians. Conversely, the emigrants, by using the road, inadvertently helped to solidify and maintain it, their passage smoothing the ruts and indicating the most trafficked paths.

However, this period was also one of intense conflict with Native American tribes whose ancestral lands were being encroached upon. The military presence, while offering protection to emigrants, was simultaneously a force of displacement and subjugation for indigenous peoples. The Fort Riley Fort Kearny Road, therefore, became a symbol of this complex and often tragic interaction – a path of progress for one group, and a symbol of loss for another. Battles and skirmishes, though perhaps not directly on the road itself, occurred in the surrounding territories, often triggered by the very expansion that the road facilitated.

Decline and Legacy

By the late 1860s and early 1870s, the golden age of the great overland trails began to wane. The arrival of the transcontinental railroad, offering a faster, safer, and infinitely more comfortable journey west, rendered the old wagon roads increasingly obsolete. Fort Riley and Fort Kearny continued their military roles for some time, but the specific need for a dedicated overland road between them diminished.

Today, the physical traces of the Fort Riley Fort Kearny Road are largely gone, swallowed by agricultural fields, modern highways, and the relentless forces of nature. Unlike some stretches of the Oregon Trail where deep wagon ruts can still be seen, the FRFKR was never as intensely used or formally constructed to leave such lasting marks. Its legacy, however, remains significant.

It serves as a powerful reminder of a specific moment in American history: a time of rapid expansion, military necessity, and immense human courage. It symbolizes the intricate network of logistics and protection that underpinned the epic westward movement. Historians and enthusiasts can still trace its approximate route through old maps and historical records, imagining the dust-choked columns of wagons and the thundering hooves of cavalry.

The Fort Riley Fort Kearny Road, though now a phantom pathway, stands as a testament to the resilience of those who built and traversed it. It was an artery of empire, a vital vein in the westward expansion of the United States, linking not just two forts, but connecting the aspirations of a young nation with the untamed vastness of its frontier. Its story, intertwined with the broader narrative of the American West, continues to echo across the plains, a silent monument to the journey that shaped a continent.