The Plumber’s Shadow: Jack Dunlap, The Forgotten Cold War Spy

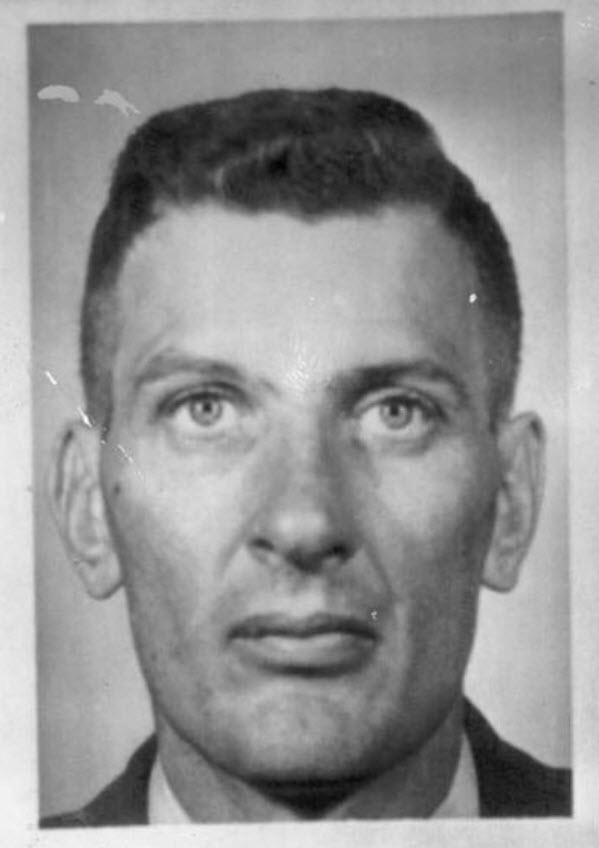

The shadows of the Cold War held many secrets, but few as unsettling as the quiet betrayal of Jack Dunlap. In the pantheon of atomic spies, names like Klaus Fuchs and the Rosenbergs loom large, etched into the collective memory as architects of catastrophic espionage. Yet, for decades, another figure remained largely obscured, his treachery only fully revealed through the painstaking work of cryptanalysts and the slow drip of declassified documents. Jack Dunlap, a seemingly innocuous US Army corporal and later a civilian documents clerk for the top-secret Manhattan Project, was a spy whose actions, driven not by ideology but by a craving for money, contributed to one of the most significant security breaches in American history. His story is a chilling reminder that sometimes, the greatest threats come not from the obvious enemy, but from within, quietly, meticulously, and almost entirely unseen.

The year is 1943. The world is engulfed in the Second World War, but beneath the surface, a new, more terrifying conflict is being forged. The Manhattan Project, a clandestine endeavor of unprecedented scale, races against time to harness the power of the atom. Its nerve center, Los Alamos, New Mexico, was a crucible of scientific genius and military secrecy, a place where the brightest minds worked in isolation, shielded from the outside world by layers of security.

It was into this intensely guarded environment that Jack Dunlap arrived. Initially serving as a US Army corporal attached to the project, he was later hired as a civilian by the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. His job description sounds mundane: a documents clerk, responsible for filing and managing the torrent of classified papers, reports, and blueprints that flowed through the nascent atomic program. This seemingly low-level position, however, granted him extraordinary access. Dunlap was a cog in the machine, but a cog positioned at a critical junction, handling documents that detailed the very blueprints of America’s atomic arsenal.

Dunlap was not a scientist, nor was he a fervent communist ideologue. Unlike Klaus Fuchs, the brilliant German-born physicist who confessed to passing atomic secrets out of deep-seated communist convictions, Dunlap’s motivations were far more base: money. He was a gambler, a heavy drinker, and a man living beyond his means. The lure of quick cash, coupled with a startling lack of moral compass, made him an easy target for Soviet intelligence.

His recruitment and modus operandi were later pieced together through a labyrinthine process involving declassified intelligence reports, FBI investigations, and, crucially, the Venona Project – a top-secret counter-intelligence program that intercepted and decrypted Soviet intelligence messages. The Venona intercepts, a treasure trove of Cold War secrets, would ultimately confirm Dunlap’s perfidy, though the full extent of his betrayal wouldn’t be known for decades.

Dunlap began his espionage activities in 1950, well after the war’s end and after the Soviet Union had already detonated its first atomic bomb. While this might suggest his actions were less critical, it’s a crucial misunderstanding. The Soviets had the bomb, yes, but they desperately needed to refine their designs, improve their efficiency, and accelerate their arms race against the United States. Dunlap provided precisely the kind of granular, technical detail that could shave years off Soviet development cycles and provide invaluable insights into American nuclear capabilities.

He systematically stole classified documents, often simply walking them out of the office in his briefcase or even under his coat. These weren’t just vague reports; they included detailed designs for nuclear weapons, information on plutonium production, data on atomic weapons testing, and even the technical specifications of the Los Alamos laboratory itself. He would then meet his Soviet handlers, often in inconspicuous locations, exchanging the stolen secrets for cash. The exact identity of all his handlers remains somewhat murky, but it’s understood he worked with multiple Soviet agents, reflecting the sophisticated network the KGB and GRU (Soviet military intelligence) had established in the United States.

While the FBI was aware of a significant Soviet espionage threat, particularly after the unmasking of Fuchs in 1950, and the subsequent arrests of Harry Gold, David Greenglass, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Dunlap operated largely under the radar. His unassuming demeanor, coupled with the sheer volume of personnel and documents flowing through Los Alamos, provided him with a perfect cover. He wasn’t a high-profile target; he was a silent leak, a continuous drip of vital information.

As the 1950s progressed, Dunlap’s life began to unravel. His gambling debts mounted, his drinking worsened, and his paranoia grew. He became increasingly reckless with the money he received from the Soviets, flashing large sums and making extravagant purchases that were inconsistent with his modest salary. This behavior eventually caught the attention of the FBI, not initially as a spy, but as a potential target for investigation regarding unexplained wealth and suspicious activities. The Bureau began to build a file on him, noting his movements and associates.

The pressure mounted. Dunlap’s superiors at Los Alamos grew suspicious of his erratic behavior and his increasingly frequent absences. He was eventually transferred to the Pentagon, where he continued to handle classified documents, extending his window of opportunity to steal secrets even further. His transfer, however, did not alleviate his personal demons. By mid-1959, Dunlap was facing an internal investigation at the Pentagon due to his poor performance and the persistent questions about his finances. The net was tightening, slowly but inexorably.

On July 22, 1959, the story of Jack Dunlap took a grim turn. His body was found in his car, parked in a remote area in Silver Spring, Maryland. The cause of death was carbon monoxide poisoning, ruled a suicide. He was 31 years old. Inside his car, investigators found a briefcase containing a pistol, a bottle of whiskey, and a note indicating his intention to end his life. The immediate conclusion was that Dunlap, overwhelmed by his personal problems and the impending exposure of his financial irregularities, had taken his own life.

But Dunlap’s death was not the end of his story; it was merely the beginning of the real investigation into his true activities. While the initial police report focused on suicide, the FBI’s ongoing, quiet surveillance quickly shifted focus. They began to connect the dots between his unexplained wealth, his secretive contacts, and the disturbing possibility that he was more than just a troubled clerk.

The true breakthrough, however, came years later, through the painstaking work of the Venona Project. Starting in the 1940s, American and British cryptanalysts had been intercepting and attempting to decrypt Soviet intelligence communications. The work was slow, laborious, and often frustrating. But piece by piece, they began to unravel the complex codes. It was through these decrypted messages that the codename "Plumber" (or sometimes "Plumber’s Assistant") began to appear in connection with highly sensitive atomic information.

After Dunlap’s death, and with the benefit of the FBI’s posthumous investigation, intelligence analysts were able to cross-reference the Venona intercepts with the biographical details and activities of Dunlap. The puzzle pieces fit. "Plumber" was Jack Dunlap. The Venona messages provided irrefutable proof of his systematic theft and delivery of atomic secrets to the Soviet Union. The full extent of his espionage, revealed by these messages, was far more extensive and damaging than initially suspected. He had been a consistent, reliable source for Soviet intelligence for years.

The revelation of Dunlap’s treachery, though confirmed by Venona in the early 1960s, was kept under wraps for decades. The Venona Project itself was one of the most closely guarded secrets of the Cold War, its existence and successes only officially acknowledged in 1995. This meant that for a long time, Dunlap remained a footnote, a figure whose full villainy was known only to a select few in the intelligence community.

How much damage did Jack Dunlap do? While he lacked the scientific depth of a Fuchs or the network of a Rosenberg, his consistent access to and theft of highly classified technical data was undeniably significant. He provided the Soviets with the intricate details of American nuclear bomb designs, production methods, and testing results. This information, though perhaps not providing the initial "secret" of the atomic bomb, certainly accelerated the Soviet Union’s nuclear program, allowing them to refine their weapons more quickly and efficiently. In the terrifying calculus of the Cold War arms race, every advantage, every shortcut, mattered.

Jack Dunlap remains a chilling footnote in the history of Cold War espionage. He was not a charismatic ideologue, nor a master manipulator. He was a man consumed by personal failings, whose mundane job granted him access to extraordinary secrets. His story is a stark reminder of the constant vulnerability inherent in even the most secure systems, and the unsettling truth that sometimes, the greatest betrayals are carried out not by grand conspirators, but by ordinary individuals, driven by the simplest and most destructive of motives: greed. His shadow, the "Plumber’s Shadow," serves as a haunting epitaph to a quiet act of treason that had profound and lasting repercussions on the global balance of power.