Blossburg: Where the Ghosts of Coal Miners Still Whisper in New Mexico’s High Desert

In the rugged embrace of northern New Mexico, where the Sangre de Cristo Mountains begin their ascent, lies a landscape of stark beauty and profound silence. The wind, a constant companion, whispers through scrub brush and piñon, carrying with it tales of ages past. But for those who listen closely, a different kind of whisper emerges from the dust and rock – the echoes of a vibrant, gritty, and ultimately vanished community known as Blossburg. This isn’t just a ghost town; it’s a testament to human endeavor, the brutal realities of industrialization, and the relentless march of time, a microcosm of America’s boom-and-bust frontier spirit.

Today, little remains of Blossburg but foundations, scattered debris, and the haunting outlines of its former glory. Yet, for a few intense decades at the turn of the 20th century, it was a throbbing heart of industry, a vital cog in the machine of westward expansion, and home to thousands who sought their fortunes, often at great personal cost, deep within the earth.

The Genesis of a Coal Town

Blossburg’s story begins, as many frontier tales do, with a discovery and a need. In the late 19th century, the expansion of railroads across the American West created an insatiable demand for fuel. Coal was king, and the vast, untapped reserves beneath the Raton Basin in northern New Mexico proved to be a veritable treasure trove. Among these rich seams was one discovered by German immigrant Carl Bloss, who, according to local lore, gave his name to the future settlement.

The Raton Coal & Coke Company, later absorbed by the powerful St. Louis, Rocky Mountain & Pacific Railway, saw the immense potential. They needed a source of high-quality coking coal – coal that, when heated in specialized ovens, produced coke, a purer form of carbon essential for smelting iron ore. In 1888, the company laid tracks, built a tipple, and began the arduous process of carving a town out of the wilderness. Blossburg was born, not organically, but by corporate design, a deliberate act of will to extract wealth from the earth.

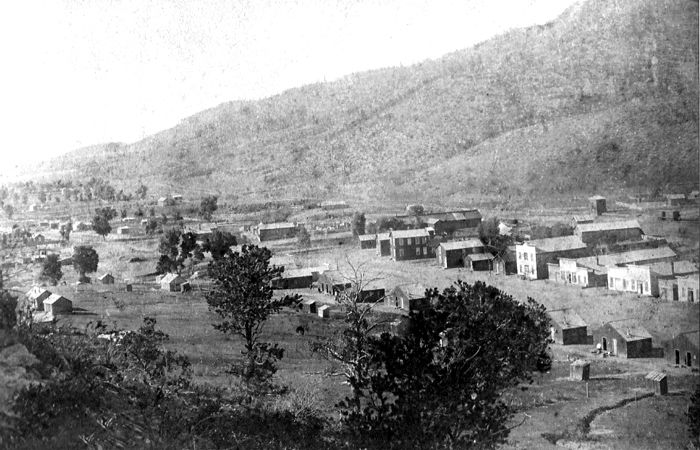

The location was strategically chosen, nestled in a canyon roughly six miles west of Raton, allowing for easy rail access to transport the valuable coal and coke. Initially, the town was a rough-and-tumble collection of tents and temporary shelters. But as the mines expanded and the workforce grew, more permanent structures began to appear. Wooden shacks gave way to more substantial company houses, a general store, a school, a church, and, inevitably, saloons.

"Little Pittsburgh" in the Desert

By the early 1900s, Blossburg was booming. Its population swelled to an estimated 2,000 residents, a remarkable figure for a remote New Mexico town. It became known as "Little Pittsburgh," a nod to its industrial might and the hundreds of beehive coke ovens that dotted the landscape, their perpetual fires casting an eerie glow against the night sky and sending plumes of acrid smoke into the clear desert air. These ovens, operating 24/7, were the town’s lifeblood, transforming raw coal into the precious coke that fueled industries across the West.

Life in Blossburg was a vibrant, often chaotic, mosaic of cultures. Miners arrived from every corner of the globe: Mexican, Italian, Slavic, Irish, German, and native-born Americans, all drawn by the promise of work, however dangerous. This melting pot of ethnicities brought with it a rich tapestry of languages, traditions, and foods, creating a unique social fabric in the otherwise harsh environment. They lived in company housing, often segregated by ethnicity, and relied heavily on the company store, a ubiquitous feature of industrial towns that provided goods but also often trapped workers in a cycle of debt.

Despite the camaraderie that often developed among men facing shared dangers, life in Blossburg was undeniably hard. The work was grueling, often performed in cramped, dark, and dangerous conditions deep underground. Accidents were tragically common – cave-ins, explosions from methane gas, and the slow, insidious onset of black lung disease were constant companions. A miner’s life expectancy was significantly lower than the national average, and every family in Blossburg knew the grim reaper’s knock on the door.

The Shadow of Labor Unrest

Beyond the physical dangers, the miners faced economic exploitation. The company owned everything: the mines, the houses, the stores, even the doctors. Wages were low, and the company store’s prices were often inflated, ensuring that workers remained beholden to their employers. This environment was ripe for unrest, and Blossburg, like many coal towns in the region, became a focal point for the nascent labor movement.

The early 20th century saw significant strikes in the Trinidad-Raton coalfields, with miners demanding better wages, safer conditions, and the right to unionize. The infamous 1913-1914 Coal Strike, one of the most violent labor disputes in American history, deeply impacted the region. While the most brutal events unfolded in nearby Ludlow, Colorado, Blossburg was not immune to the tensions. Miners walked off the job, facing down company-hired guards and the state militia. These strikes, often met with violent suppression, highlighted the deep chasm between the powerful coal companies and the desperate workers, leaving an indelible mark on the town’s collective memory. The quest for dignity and fair treatment was a constant battle, often fought and lost in the shadows of the coke ovens.

The Inevitable Decline

Despite its initial prosperity and the sheer grit of its inhabitants, Blossburg’s fate was sealed by a combination of factors, both economic and environmental. By the 1920s, the easily accessible coal seams were beginning to play out. Mining became more difficult, less profitable, and increasingly dangerous.

Adding to the woes, the demand for coke began to wane as steel production methods evolved and other fuels, like oil and natural gas, gained prominence. A devastating fire in 1919 swept through a significant portion of the town, destroying homes and businesses and delivering a crippling blow from which Blossburg never fully recovered. While some rebuilding occurred, the writing was on the wall.

The St. Louis, Rocky Mountain & Pacific Railway, facing declining profits and shifting energy markets, began to scale back operations. Miners, seeing the inevitable, started to drift away, seeking work in other coalfields or entirely different industries. The company gradually dismantled its infrastructure, salvaging what it could. Houses were moved or torn down, tracks were pulled up, and the coke ovens, once roaring with industry, slowly cooled, their fires extinguished forever. By the 1930s, the vibrant "Little Pittsburgh" was a mere shadow of its former self, and by the 1940s, it was largely abandoned.

A Ghostly Legacy

Today, visiting Blossburg is a pilgrimage into silence. The journey itself is a reminder of its isolation, involving a drive along a dirt road west of Raton, past the modern coal operations that continue in the region. There are no historical markers, no visitor centers, just the raw, unadulterated remnants of a forgotten past.

What remains are primarily foundations of buildings, rectangular outlines in the earth that hint at former homes, the school, or the company store. The most striking features are the skeletal remains of the beehive coke ovens. Rows upon rows of these stone and brick structures, now crumbling and overgrown, stand as silent sentinels, their openings gaping like empty eyes staring out at the indifferent landscape. Walking among them, one can almost smell the coal smoke, hear the clang of shovels, and feel the heat radiating from their ancient interiors.

Scattered across the site are fragments of everyday life: shards of pottery, rusted metal tools, pieces of glass, and the ubiquitous black dust of coal that still permeates the soil. These artifacts are poignant reminders of the thousands who lived, worked, loved, and died here. The wind, which once carried the shouts of children and the rumble of coal cars, now carries only the rustle of dry grass and the whisper of the forgotten.

Blossburg’s legacy extends beyond its physical ruins. It stands as a powerful symbol of the human cost of industrial progress, the struggles for labor rights, and the ephemeral nature of even the most robust communities when economic forces shift. It reminds us of the sacrifices made by generations of immigrant workers who fueled America’s industrial might, often living in harsh conditions and facing constant danger.

In a broader sense, Blossburg is a testament to the boom-and-bust cycle that characterized much of the American West. Towns sprang up overnight around a single resource – gold, silver, timber, or coal – only to vanish just as quickly when the resource dwindled or the economy changed. These ghost towns are not just empty spaces; they are archives of human experience, holding stories of ambition, hardship, community, and ultimately, loss.

As the sun sets over the rugged peaks surrounding Blossburg, casting long shadows across the decaying coke ovens, it’s easy to feel the weight of history. The whispers in the wind are not just the sound of the desert; they are the voices of the miners, their families, and the vibrant community they forged against all odds. Blossburg may be gone, but its story, etched into the New Mexico landscape and the annals of industrial history, continues to resonate, reminding us that even in the silence of a ghost town, the past has a powerful voice, if only we take the time to listen.