The Wisdom of Generations: How Traditional Ecological Knowledge is Reshaping Conservation

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

In the vast, interconnected tapestry of our planet, a quiet crisis unfolds. Biodiversity plummets, climate change accelerates, and ecosystems buckle under unprecedented pressure. As scientists and policymakers grapple with these monumental challenges, a profound and often overlooked source of wisdom is emerging from the shadows: Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). This isn’t merely anecdotal folklore; it’s a dynamic, intergenerational body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs concerning the relationship of living beings (including humans) with their environment, deeply rooted in the long-term observation and experience of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

For too long, Western scientific paradigms have dominated conservation efforts, often sidelining or even dismissing the intricate understanding held by those who have lived in harmony with the land for millennia. But as the limitations of purely scientific, top-down approaches become apparent, a growing movement is recognizing TEK not just as a valuable supplement, but as an indispensable cornerstone for effective, equitable, and sustainable conservation in the 21st century.

More Than Data: A Holistic Worldview

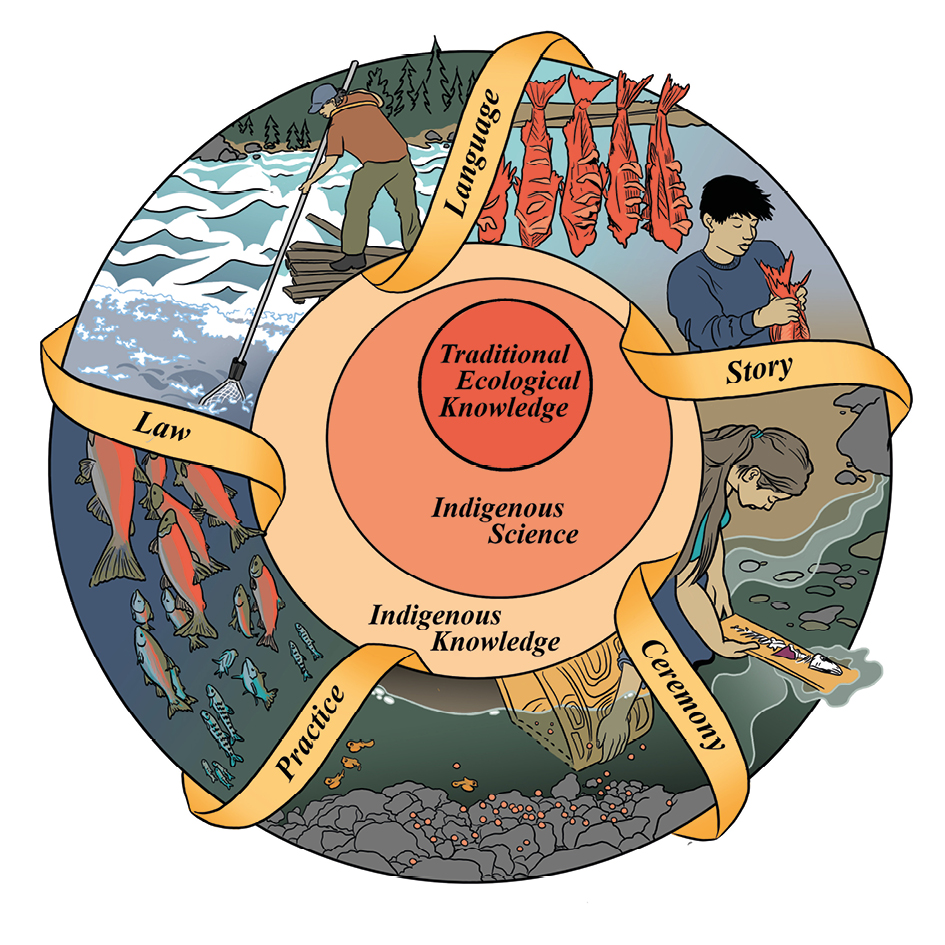

What exactly is TEK? It’s far more than a collection of facts about plants and animals. It encompasses a holistic worldview that sees humans not as separate from nature, but as integral parts of an intricate web of life. It includes:

- Empirical Knowledge: Detailed understanding of species behavior, ecological processes, weather patterns, and resource availability, often spanning hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

- Practices: Sustainable harvesting techniques, traditional agricultural methods, fire management, water conservation, and land use planning that promote ecological resilience.

- Beliefs and Values: Spiritual connections to the land, ethical frameworks for resource use, and a sense of responsibility towards future generations, often guided by principles of reciprocity and respect.

Unlike the often reductionist approach of Western science, TEK is inherently adaptive, localized, and orally transmitted, evolving with changing environmental conditions and passed down through stories, ceremonies, and practical apprenticeships. This deep, lived experience offers insights that satellite imagery and laboratory analyses alone cannot provide.

The Indispensable Contributions of TEK to Conservation

The integration of TEK offers tangible benefits across various facets of conservation:

1. Biodiversity Protection and Monitoring:

Indigenous communities often inhabit and manage areas of immense biodiversity. Their knowledge is critical for identifying endangered species, understanding population dynamics, and recognizing subtle environmental changes that precede scientific detection. For example, in the Arctic, Inuit communities have observed shifts in ice patterns and animal migrations long before scientific instruments confirmed climate change impacts, providing crucial early warning systems. Their knowledge of specific plant properties, animal behaviors, and ecosystem interactions is unparalleled.

2. Sustainable Resource Management:

TEK provides blueprints for living sustainably within ecological limits. Traditional fishing, hunting, and harvesting practices often incorporate sophisticated mechanisms for ensuring long-term viability, such as seasonal restrictions, rotational use of areas, and taboos on over-exploitation. In the Pacific, traditional marine protected areas, known as "ra’ui" in some Polynesian cultures, were established centuries ago based on observations of fish stocks and coral health, demonstrating an innate understanding of marine ecology and resource replenishment. These indigenous-managed areas frequently boast higher biodiversity than non-indigenous ones.

3. Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation:

Indigenous peoples are often on the front lines of climate change, but they also possess unique strategies for adaptation. Their knowledge of local weather patterns, traditional food systems resilient to extreme conditions, and methods for managing water resources are invaluable. Furthermore, traditional land management, such as prescribed burning, can mitigate the risk of catastrophic wildfires, as seen in Australia and parts of North America.

4. Fire Management: A Fiery Example:

Perhaps one of the most compelling examples of TEK’s power is in fire management. For millennia, Indigenous Australians have practiced "cultural burning," a nuanced approach involving small, cool fires that clear undergrowth, promote biodiversity, and prevent large, destructive infernos. As Victor Steffensen, an Indigenous fire practitioner, states, "The land tells you how to burn it. It’s not about lighting a match, it’s about reading the country." In contrast, Western fire suppression policies have led to a build-up of fuel, contributing to the unprecedented scale of recent bushfires. Now, fire agencies are increasingly collaborating with Indigenous communities to re-learn and re-implement these ancient practices.

5. Forest Conservation: The Amazonian Shield:

Indigenous territories in the Amazon rainforest are often the most effective barriers against deforestation, outperforming even government-protected areas. The traditional land use practices and stewardship of Indigenous communities are directly responsible for safeguarding vast swathes of the world’s most vital rainforests and the immense biodiversity within them. Their intricate knowledge of forest ecosystems, medicinal plants, and sustainable resource extraction methods provides a living model for conservation.

Challenges and the Path Forward: Towards Co-Management

Despite its immense value, integrating TEK into mainstream conservation is not without its challenges. Historically, Indigenous knowledge has been marginalized, dismissed, or even exploited. Concerns around intellectual property rights, the potential for appropriation, and ensuring genuine partnership rather than tokenistic inclusion are paramount.

- Recognition and Respect: The first step is to genuinely recognize TEK as a valid and rigorous knowledge system, equal in stature to Western science. This requires overcoming historical biases and power imbalances.

- Ethical Engagement: Any collaboration must be built on principles of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC), ensuring Indigenous communities have full control over their knowledge and how it is used. Benefits must be shared equitably.

- Capacity Building: Supporting Indigenous communities to document, revitalize, and transmit their knowledge to younger generations is crucial, especially in the face of cultural erosion driven by globalization and urbanization.

- Bridging Knowledge Systems: The goal is not to replace Western science with TEK, but to foster a synergistic approach. As Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall famously articulated, it’s about "Two-Eyed Seeing" – learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledge and ways of knowing, and using both eyes together for the benefit of all. This means fostering dialogue, mutual learning, and collaborative research that respects the integrity of both systems.

- Policy and Legal Frameworks: International declarations like the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) provide a framework for recognizing Indigenous rights to land, resources, and self-determination, which are fundamental to empowering their role in conservation.

A Future Woven with Wisdom

The urgency of the global environmental crisis demands a radical rethink of our approach to conservation. It calls for humility, openness, and a willingness to learn from those who have demonstrated sustainable living for millennia. Traditional Ecological Knowledge is not a romanticized relic of the past; it is a living, evolving blueprint for a more resilient and equitable future.

By genuinely partnering with Indigenous peoples and local communities, by valuing their deep ecological wisdom, and by integrating TEK into conservation strategies, we can unlock solutions that are not only scientifically sound but also culturally appropriate, socially just, and truly sustainable. The path to healing our planet lies not just in technological innovation, but in reconnecting with the ancient wisdom that understands our place within, not above, the natural world. It is time to listen to the land, and to those who have always listened to it.