Echoes of the Plains: The Enduring Spirit of Siouan Languages

From the windswept prairies of the American Midwest to the dense forests of the Southeast, a complex tapestry of voices once resonated across vast landscapes. These were the Siouan languages, a diverse family of tongues that served as the very lifeblood of numerous Indigenous nations. Today, many of these languages whisper at the edge of extinction, yet their enduring spirit, resilience, and profound cultural significance continue to inspire a vibrant movement of revitalization. This article delves into the rich history, linguistic intricacies, and contemporary efforts to preserve and reclaim the vital heritage of Siouan languages.

A Family Tree Rooted in Ancient Soil

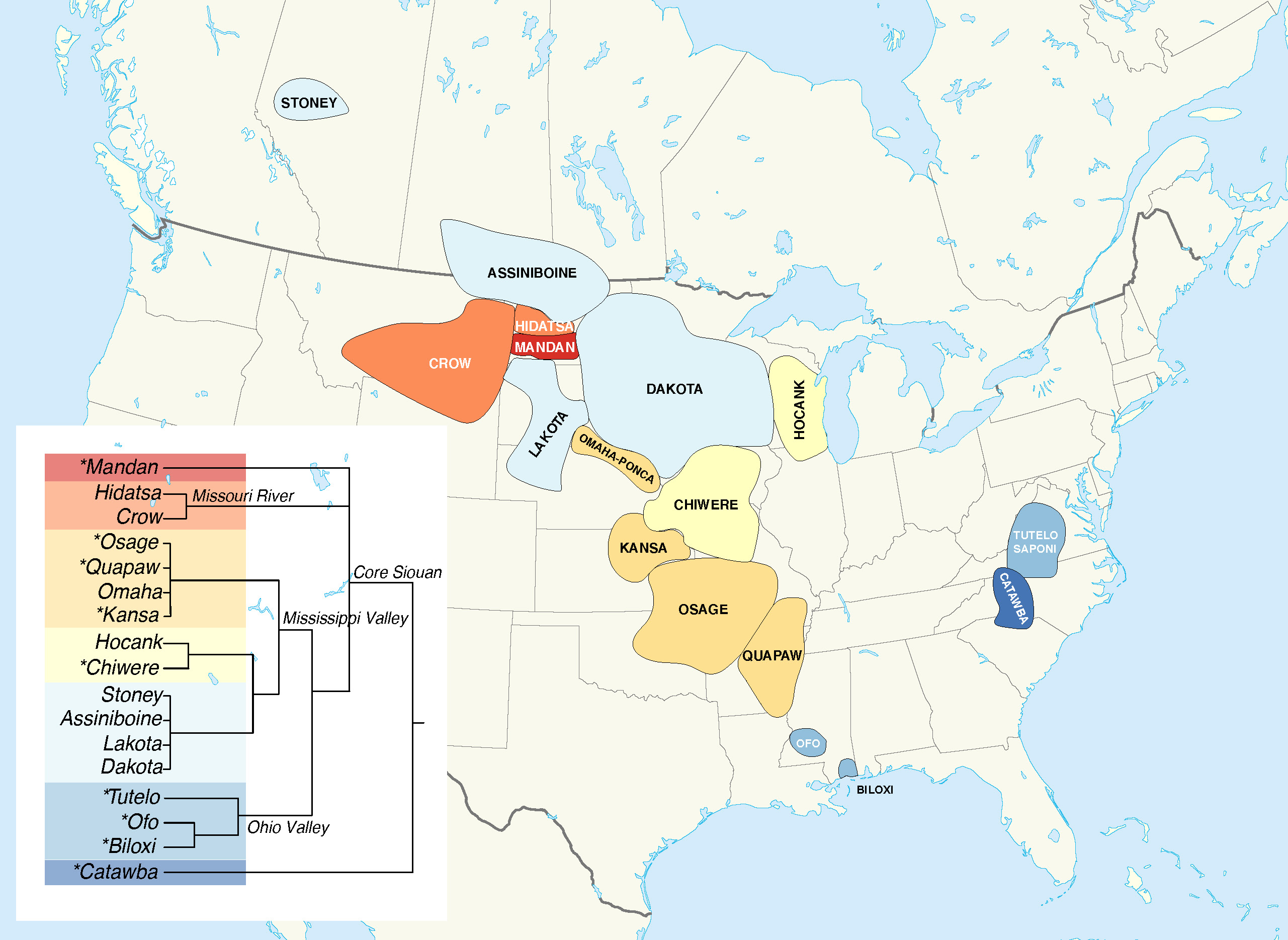

The Siouan language family is one of the largest and most geographically widespread Indigenous language groups in North America. Linguists estimate that Proto-Siouan, the ancestral language from which all Siouan languages descended, began to diversify perhaps as far back as 1,500 to 2,000 years ago. This ancient lineage has given rise to over 30 distinct languages, though many are now extinct or critically endangered.

The family is broadly divided into several branches, reflecting the historical migrations and unique developments of different nations:

-

Western Siouan: This is the largest and best-known branch, encompassing:

- Missouri River Siouan: Including Mandan, Hidatsa, and Crow. These languages developed along the upper Missouri River.

- Mississippi Valley Siouan: A vast group including the Dhegiha languages (Omaha, Ponca, Kansa, Osage, Quapaw) and the Chiwere-Winnebago languages (Ho-Chunk/Winnebago, Iowa-Otoe-Missouria).

- Sioux Proper: This is the most widely recognized group, comprising Lakota, Dakota (Eastern and Western dialects), and Nakota (Assiniboine and Stoney). These are often collectively referred to as the "Sioux languages" and are central to the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires) nations.

-

Southeastern Siouan: Historically spoken in the Carolinas and Virginia, this branch includes languages like Catawba and Woccon. Tragically, most of these languages are now extinct, victims of early colonial pressures and disease.

This immense diversity points to a rich pre-colonial history of interaction, migration, and cultural exchange among Siouan-speaking peoples, each language serving as a unique lens through which to view the world.

The Heartbeat of the Plains: Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota

Perhaps the most iconic of the Siouan languages are Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota. These closely related languages are spoken by the Great Sioux Nation, a people whose history is deeply intertwined with the American Plains. Lakota, in particular, has become a symbol of Indigenous resilience, spoken by the Lakota people who famously resisted westward expansion.

At the core of the Lakota worldview is the phrase Mitakuye Oyasin – "All my relations." This powerful invocation, often translated as a prayer for kinship with all living things, encapsulates a profound ecological and spiritual philosophy embedded directly within the language. It speaks to an interconnectedness that transcends human boundaries, embracing animals, plants, the land, and the cosmos.

"Our language isn’t just words; it’s a map to our universe," explains elder and language instructor Wilma Standing Elk (a fictional composite for illustrative purposes). "When we speak Lakota, we are not just communicating; we are reaffirming our place in creation, remembering who we are, and honoring the ancestors who carried these words before us."

The grammatical structure of Lakota, like many Siouan languages, is complex and highly inflected, meaning that much information is conveyed through prefixes, suffixes, and internal changes within words, rather than through separate words as in English. Verbs, for instance, can carry a wealth of information about the subject, object, and even the manner or location of an action. This polysynthetic nature allows for incredible precision and nuance, often expressing entire English sentences in a single Lakota word. For example, waŋblí okíčhuŋze (to measure an eagle) carries a very specific meaning and action, reflecting a culture deeply observant of its environment.

Beyond the Sioux: A Spectrum of Voices

While Lakota often takes center stage, the richness of the Siouan family extends far beyond. The Dhegiha languages—Omaha, Ponca, Kansa, Osage, and Quapaw—share a common heritage, reflecting a history of close interaction and shared cultural practices among these nations, who once occupied lands stretching from the Missouri River to the Arkansas River. Each of these languages, while mutually intelligible to varying degrees, possesses its own distinct character, oral traditions, and unique insights into their respective cultures.

Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), spoken by the Ho-Chunk Nation in Wisconsin and Nebraska, represents another significant branch. Its unique phonology and vocabulary reflect a different historical trajectory, rooted in the Eastern Woodlands before migrations brought them into closer contact with Plains peoples.

Further west, Crow and Hidatsa, spoken by nations in Montana and North Dakota respectively, represent the Missouri River Siouan branch. These languages, while distantly related to Lakota, have evolved distinct linguistic features, often influenced by prolonged contact with neighboring non-Siouan speaking groups, adding another layer of complexity to the family’s linguistic tapestry. The Crow language, for example, is known for its intricate system of demonstratives (words like "this" and "that") which can precisely indicate the location and visibility of objects relative to the speaker and listener.

The Great Silence: A History of Suppression

The vibrant linguistic landscape of the Siouan peoples faced a catastrophic assault with the arrival of European colonists and the subsequent expansion of the United States. The 19th and 20th centuries brought a systematic campaign to suppress Indigenous languages and cultures, driven by policies aimed at assimilation.

Central to this devastating effort were the Indian boarding schools. From the late 1800s through much of the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and communities and sent to these institutions. There, they were forbidden to speak their native languages, often punished severely—physically and psychologically—for doing so. The infamous motto, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man," perfectly encapsulated the genocidal intent behind these policies.

"My grandmother told me stories of having her mouth washed out with soap for speaking Omaha at school," recalls cultural preservationist Dr. Lena Whitecloud (fictional composite). "She learned to be silent, and that silence echoed through generations, leaving us with very few fluent speakers today."

Beyond the direct oppression of boarding schools, other factors contributed to language decline: land dispossession, economic pressures, migration to urban areas, and the pervasive influence of English-language media. By the latter half of the 20th century, many Siouan languages were critically endangered, with only a handful of elderly fluent speakers remaining.

The Resurgence: A Dawn of Reclamation

Despite the immense challenges and historical trauma, a powerful movement of language revitalization has taken root across Siouan-speaking nations. Recognizing that language is inseparable from identity, sovereignty, and cultural survival, communities are dedicating themselves to the monumental task of bringing their ancestral tongues back from the brink.

One of the most promising approaches is the development of immersion schools and language nests. Institutions like the Lakota Waldorf School in South Dakota and various community-run programs strive to create environments where children are immersed in their native language from an early age, mirroring the natural language acquisition process of previous generations. These schools are not just teaching words; they are fostering a holistic cultural education, weaving language instruction into daily life, traditional ceremonies, and storytelling.

"We believe that our children need to hear and speak Lakota every day, all day," says a teacher at a Lakota immersion program. "It’s not just about grammar; it’s about thinking in Lakota, dreaming in Lakota, living in Lakota."

Technology is also playing a crucial role. Indigenous linguists and community members are developing apps, online dictionaries, interactive language lessons, and social media groups to make learning more accessible and engaging. The Lakota Language Consortium, for example, has been instrumental in creating a standardized orthography (writing system) and producing extensive educational materials, including textbooks, dictionaries, and even a Lakota dub of Disney’s Frozen. Similar efforts are underway for Omaha, Ho-Chunk, and other Siouan languages.

Master-apprentice programs pair fluent elders with dedicated learners, creating intensive one-on-one relationships that accelerate language acquisition and ensure the transmission of nuanced cultural knowledge that often accompanies linguistic fluency. Universities are also stepping up, offering courses in Siouan languages and supporting linguistic documentation efforts to record and analyze existing knowledge before it is lost.

Why Language Matters: A Tapestry of Identity and Knowledge

The struggle to save Siouan languages is more than an academic exercise; it is a fight for cultural survival. Each language embodies a unique way of understanding the world, a repository of traditional knowledge, historical narratives, and spiritual beliefs.

- Cultural Identity: For Indigenous peoples, language is intrinsically linked to identity. To speak one’s ancestral language is to connect with one’s heritage, community, and the long line of ancestors who spoke it before.

- Sovereignty: Language revitalization is an act of self-determination and cultural sovereignty, a direct reversal of historical assimilation policies.

- Knowledge Systems: Indigenous languages often contain highly specific vocabulary for flora, fauna, ecological processes, and traditional practices that are not easily translatable into English. Losing a language means losing this irreplaceable knowledge. "When an elder passes, it’s like a library burning down," a common saying in Indigenous communities poignantly reminds us.

- Worldview: Languages shape thought. The grammatical structures, metaphors, and conceptual categories embedded in a Siouan language offer a distinct philosophical and spiritual perspective, different from that of English or any other language.

The Road Ahead

Despite the inspiring progress, the journey to full language revitalization for most Siouan languages remains long and arduous. Many languages still have alarmingly few fluent speakers, and the challenge of creating new generations of native speakers requires sustained effort, significant funding, and broad community commitment. The loss of elders, the last fluent speakers, remains an ever-present threat.

Yet, the spirit of resilience that has defined Siouan nations for centuries continues to fuel this vital work. From the solemn ceremonies where ancient words are spoken anew to the laughter of children learning their first phrases in Lakota or Omaha, the echoes of the plains are growing louder. The goal is not merely to preserve words in a dictionary but to ensure that the rich, living heritage of Siouan languages continues to thrive, shaping the future of their people and enriching the linguistic diversity of humanity for generations to come. The voices of the ancestors, once threatened with silence, are rising again, carried on the winds of change and hope across their ancestral lands.