The Ghost Fort of Florida: Tracing the Faded Footprints of Fort Gardiner

Central Florida today is a tapestry of sprawling cattle ranches, citrus groves, and burgeoning communities, where the hum of traffic and the distant lowing of cattle define the soundscape. Yet, beneath this veneer of modern life lies a wilderness that once served as a brutal, unforgiving stage for one of America’s most protracted and forgotten conflicts: the Second Seminole War. And deep within this landscape, near the tranquil waters of Lake Kissimmee, exists a historical echo, a phantom outpost known as Fort Gardiner. It is a fort without walls, a monument without stone, its physical traces long reclaimed by the very wilderness it once sought to tame. Yet, its story, though etched only in the pages of history and the whispers of the wind, is crucial to understanding the genesis of modern Florida and the harsh realities of frontier warfare.

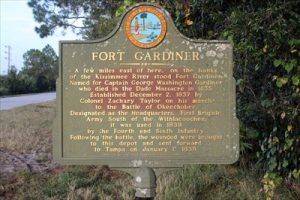

To journey to Fort Gardiner today is not to visit a reconstructed historical site or a preserved ruin. Instead, it is an exercise in historical imagination, a pilgrimage to a point on a map marked by a humble historical plaque, often nestled on private ranchland, inaccessible to the casual visitor. This absence of physical presence, however, paradoxically amplifies its significance. Fort Gardiner, established in late 1837 or early 1838, stands as a potent symbol of the ephemeral nature of military outposts in a hostile environment, and the profound challenges faced by the United States Army in its relentless campaign against the resilient Seminole people.

The Second Seminole War (1835-1842) was not a conventional conflict. It was a brutal, often frustrating guerrilla war fought across a vast, subtropical wilderness of dense hammocks, impenetrable swamps, and endless sawgrass prairies. The Seminoles, masters of their environment, leveraged the terrain to their advantage, employing hit-and-run tactics that baffled and demoralized the better-equipped, but geographically disadvantaged, American forces. For the U.S. Army, the war was less about decisive battles and more about logistics, endurance, and the slow, grinding process of attrition. It was in this context that a network of small, temporary forts became absolutely vital.

These forts, often little more than log palisades enclosing tents or crude shelters, served multiple critical functions. They were supply depots, distributing essential provisions to troops operating deep in the interior. They acted as staging grounds for patrols and larger expeditions, offering a temporary base from which to launch operations. They provided rudimentary medical care for soldiers ravaged not just by Seminole arrows and bullets, but by the far deadlier scourges of malaria, yellow fever, and dysentery that thrived in the humid Florida climate. And, perhaps most importantly, they represented a tenuous assertion of American presence and control in a territory fiercely defended by its indigenous inhabitants.

Fort Gardiner, named after Captain George W. Gardiner of the 2nd U.S. Artillery, was strategically located near the headwaters of the Kissimmee River, a crucial artery for penetrating the central Florida wilderness. Its position allowed for the logistical support of troops pushing south towards the vast, unexplored regions of the Everglades, areas where the Seminoles sought refuge and continued their resistance. The fort’s life, though relatively brief, was punctuated by significant historical moments, none more prominent than its association with Colonel Zachary Taylor, a future President of the United States.

It was from Fort Gardiner that Taylor, then a colonel in command of a mixed force of U.S. Army regulars, Missouri Volunteers, and a contingent of Delaware and Shawnee scouts, launched his infamous expedition that culminated in the Battle of Lake Okeechobee on December 25, 1837. Taylor’s objective was clear: to find and engage a large concentration of Seminole warriors led by Chiefs Alligator and Abiaka (Sam Jones) who were reportedly gathered in the remote cypress swamps south of Lake Okeechobee. The march itself was a testament to the sheer difficulty of the campaign. Soldiers slogged through waist-deep water, battled thick sawgrass that cut like razors, and endured the constant torment of mosquitoes and other biting insects, all while under the ever-present threat of Seminole ambush.

Taylor’s own reports vividly detail the arduous conditions. Writing to his superiors, he described the terrain as "a country of swamps, ponds, and hammocks, almost impenetrable, and in many places covered with water from one to three feet deep." The men, he noted, were "exposed to the vicissitudes of the weather, and compelled to wade day after day through the water." This brutal environment was the true enemy, more so than the Seminole warriors themselves, who, though fewer in number, were intimately familiar with every twist and turn of the landscape.

The Battle of Lake Okeechobee was one of the few pitched battles of the Second Seminole War, and a costly one for the American forces. Taylor’s men, advancing in close order through the sawgrass, faced a well-entrenched Seminole line. The fighting was fierce, hand-to-hand in places, with heavy casualties on both sides. While Taylor ultimately claimed victory, forcing the Seminoles to retreat, the cost was high. Over 26 American soldiers were killed and 112 wounded, many severely. It was a Pyrrhic victory that underscored the futility of conventional tactics against a determined, adaptive foe.

Fort Gardiner played a crucial role as the staging point for this expedition and, perhaps more grimly, as the initial destination for the wounded returning from Okeechobee. Imagine the scene: exhausted, mud-caked soldiers carrying their injured comrades back to the crude fort, where overwhelmed surgeons worked with limited supplies in the stifling heat. The cries of the wounded, the smell of blood and antiseptic, the constant drone of insects – it was a scene of unvarnished suffering that defined much of the war.

Beyond the major expeditions, life at Fort Gardiner was likely a mix of monotonous routine and sudden terror. Soldiers would have spent their days on fatigue duty, chopping wood, digging latrines, repairing fortifications, or standing guard. Patrols would venture out into the surrounding wilderness, always on alert for signs of Seminole activity. The isolation was profound, communication with the outside world slow and unreliable. Disease was a constant, invisible enemy, felling more soldiers than any Seminole rifle. The simple act of survival in such an environment required immense fortitude.

The Seminoles, meanwhile, viewed these forts as unwelcome incursions into their ancestral lands. While they rarely launched direct assaults on well-defended fortifications, they harassed supply lines, ambushed patrols, and generally made life miserable for the soldiers. Their goal was not necessarily to destroy the forts, but to make the American presence so costly and uncomfortable that the invaders would eventually abandon their efforts. Their resilience, born of a deep spiritual connection to the land and a fierce determination to remain free, was legendary.

As the Second Seminole War slowly wound down to its unsatisfying conclusion in 1842 – a war that ultimately cost the U.S. government an estimated $20-40 million (a staggering sum at the time) and claimed the lives of over 1,500 American soldiers, not to mention countless Seminoles – the need for remote outposts like Fort Gardiner diminished. One by one, these temporary forts were abandoned. Their timber structures, never intended for permanence, were often dismantled for salvage or simply left to the elements.

Nature, ever patient, swiftly reclaimed its territory. The palisades rotted, the tents disintegrated, and the crude shelters collapsed. The dense vegetation of Florida’s interior quickly grew over the disturbed earth, erasing all but the most subtle evidence of human occupation. Today, the exact site of Fort Gardiner is known primarily through historical maps and archaeological surveys, some of which have identified pottery shards, musket balls, and other small artifacts that hint at the fort’s former existence. Yet, for the most part, the fort exists as a "ghost fort," a historical memory rather than a tangible place.

This disappearance is not unique to Fort Gardiner. Many of the temporary forts of the Seminole Wars have met a similar fate, their locations now marked by little more than a roadside sign or a vague historical reference. Their absence, however, serves as a powerful reminder of the nature of the conflict and the transient footprint of military operations in a wilderness setting. It also underscores the challenge of preserving and interpreting a history that lacks physical monuments.

Why, then, should we remember Fort Gardiner? Its significance lies not in its grandeur or its preservation, but in its representation. It stands for the thousands of nameless soldiers who endured unimaginable hardships in the Florida wilderness. It symbolizes the logistical nightmares and strategic complexities of fighting an indigenous population on their home turf. It reminds us of the profound human cost of expansion and conflict, and the brutal collision of cultures that shaped early America.

Fort Gardiner, though physically absent, speaks volumes about the past. It compels us to look beyond the paved roads and manicured lawns of modern Florida and to imagine the vast, untamed wilderness that once defined it. It invites us to consider the courage and suffering of all who walked that land – the soldiers, the Seminoles, the pioneers – and to acknowledge the layers of history that lie beneath our feet. In an era where physical landmarks often dominate historical narratives, the ghost fort of Fort Gardiner serves as a potent reminder that some of the most compelling stories are found not in what remains, but in what has been lost, and in the enduring power of memory to bridge the gap between past and present. Its faded footprints, though invisible, continue to mark a critical path in Florida’s complex historical journey.