Echoes in the Pine Barrens: The Forgotten Saga of Fort Houston, Florida

The Florida sun, relentless and ancient, beats down on the quiet expanse of Suwannee County, where pine forests whisper secrets to the breeze and the Suwannee River carves its timeless path. Today, the landscape near Live Oak is largely pastoral, dotted with farms and small communities, a picture of tranquil rural America. Yet, beneath this veneer of serenity lies a forgotten history, etched not in grand monuments or preserved battlefields, but in the very soil itself. Here, over 180 years ago, stood Fort Houston, a humble wooden outpost that played a vital, if often overlooked, role in one of America’s most brutal and protracted conflicts: the Second Seminole War.

Fort Houston was not a towering stone fortress designed to withstand sieges, nor was it the site of a legendary battle that turned the tide of war. Instead, it was a practical, often desolate, stockade – a temporary bulwark against a relentless enemy and an unforgiving wilderness. Its story is a microcosm of the larger struggle, reflecting the desperate realities faced by soldiers and settlers alike in a frontier often defined by disease, isolation, and the constant threat of ambush.

A Land in Turmoil: The Second Seminole War

To understand Fort Houston, one must first grasp the turbulent era of its birth. The 1830s in Florida were marked by escalating tensions between the burgeoning American frontier and the Seminole people, a confederation of Native American groups, including Creek refugees, who had forged a unique culture in the state’s swamps and hammocks. The federal government, driven by expansionist policies and the infamous Indian Removal Act of 1830, sought to forcibly relocate all Native Americans west of the Mississippi River. The Seminoles, led by charismatic figures like Osceola and Micanopy, fiercely resisted, viewing Florida as their ancestral home and a sanctuary from forced removal.

This resistance ignited the Second Seminole War (1835-1842), a conflict that would become the longest and costliest Indian war in U.S. history. It was a war of attrition fought in an environment utterly alien to most American soldiers – dense cypress swamps, impenetrable palmetto thickets, and mosquito-infested pine barrens. The Seminoles, masters of guerrilla warfare, used the landscape to their advantage, launching swift, devastating raids and melting back into the wilderness.

The war began with explosive violence. In December 1835, Major Francis L. Dade and his company of 108 men were ambushed and almost entirely wiped out near present-day Bushnell. This massacre, along with simultaneous attacks on sugar plantations and scattered settlements, sent shockwaves through the territory and spurred the U.S. Army to establish a network of defensive outposts across central and northern Florida. Fort Houston was one such critical link in this chain.

The Birth of Fort Houston: A Refuge in the Wilderness

Established in early 1837, Fort Houston was strategically located in Suwannee County, near the convergence of the Suwannee and Santa Fe rivers. Its primary purpose was multi-faceted: to protect the sparse settler population from Seminole raids, to serve as a supply depot for troops operating in the region, and to act as a staging point for patrols into the surrounding wilderness. The fort was named after Lieutenant G. M. Houston, though historical records sometimes differ on the exact spelling or the individual’s full name, a common ambiguity in the hastily erected outposts of the frontier.

Like many forts of its kind, Fort Houston was a relatively simple affair. It likely consisted of a log stockade, perhaps 100 to 150 feet square, with blockhouses at the corners for defensive fire. Inside, there would have been crude barracks for soldiers, a storehouse for provisions, and possibly a small hospital or sick bay. The construction was swift and utilitarian, built with the materials at hand – local pine and cypress timber. It was a beacon of safety for settlers, a place where families could seek refuge during times of heightened danger, often bringing their livestock and meager possessions within its protective walls.

"These forts were not meant for comfort," notes historian John K. Mahon in his seminal work, History of the Second Seminole War, 1835-1842. "They were functional, temporary structures, reflecting the transient nature of the conflict itself. Life within their walls was harsh, a constant battle against boredom, disease, and the ever-present threat of attack."

Life and Death at the Outpost

Life at Fort Houston, like other frontier garrisons, was a grueling test of endurance. Soldiers – a mix of regular U.S. Army troops, state militia, and volunteer companies – faced immense challenges. The suffocating humidity, swarms of mosquitoes, and prevalence of diseases like malaria, dysentery, and yellow fever were often more deadly than Seminole bullets. Medical care was rudimentary, and many succumbed to illness. One common observation from military reports of the era was that disease claimed more lives than direct combat.

The daily routine revolved around vigilance and labor. Patrols ventured out into the dense forests, searching for Seminole encampments or tracking raiding parties. Building and maintaining the fort, clearing land, and guarding supplies were constant tasks. Food, often salt pork, hardtack, and cornmeal, was monotonous and frequently spoiled in the heat. Morale could be low, exacerbated by the isolation and the seemingly endless nature of the war.

"The soldiers endured unimaginable hardships," wrote a contemporary observer. "The climate was their greatest enemy, draining their strength and spirit. They fought not only a cunning foe but also the very land itself."

While Fort Houston may not have been the scene of major pitched battles, it was undoubtedly involved in numerous skirmishes and patrols. Its very existence served to disrupt Seminole movements and protect crucial supply lines. Reports from other nearby forts, like Fort King or Fort White, often mention detachments being sent to or from Fort Houston, highlighting its role as an interconnected part of the military strategy. Settlers seeking protection would often huddle within its walls, listening to the sounds of the night, knowing that beyond the palisades lay a dangerous and unpredictable world.

The Waning Years and Demise

By 1842, the Second Seminole War officially drew to a close. Though no formal treaty was ever signed, the Seminole resistance had been largely broken. Most of the Seminoles had been forcibly removed to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), though a small, resilient band retreated deep into the Everglades, where their descendants remain to this day. With the perceived end of the Indian threat, the need for a vast network of frontier forts diminished.

Fort Houston, like many of its brethren, was gradually abandoned. Its temporary construction meant it was never intended for permanence. The wooden structures would have quickly fallen into disrepair, reclaimed by the relentless Florida climate and the encroaching wilderness. Timbers might have been scavenged by nearby settlers for their own constructions, and the ground would have slowly erased any definitive traces. The strategic importance it once held vanished with the changing geopolitical landscape.

A Forgotten Legacy, A Silent Reminder

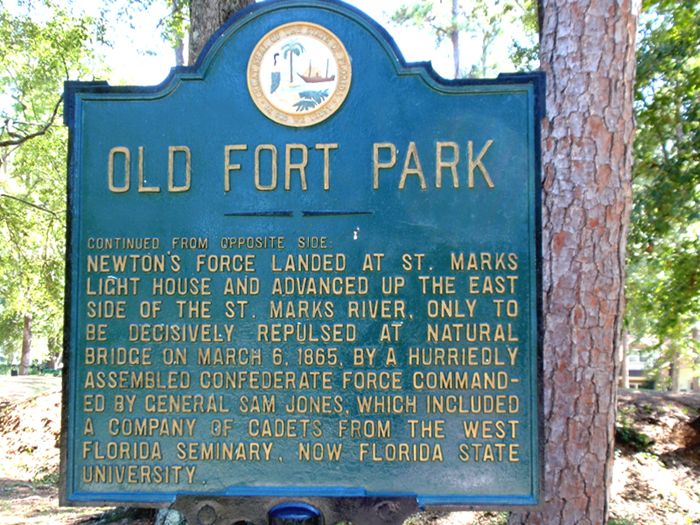

Today, little physical evidence of Fort Houston remains. The exact site is believed to be on private land, near the Suwannee River, its memory largely preserved through historical markers erected by local historical societies and the state of Florida. These markers, often placed roadside, offer a tantalizing glimpse into a past that has otherwise faded from view.

The absence of grand ruins or a preserved site does not diminish the fort’s historical significance. Instead, it underscores a crucial aspect of Florida’s frontier history: the transient nature of these outposts. They were built out of necessity, served their purpose, and then dissolved back into the landscape, leaving behind only echoes.

Fort Houston, though physically ephemeral, represents:

- The immense human cost of the Second Seminole War: Not just in battles, but in the daily grind of survival against disease, isolation, and constant threat.

- The brutal efficiency of the U.S. expansionist policy: How a network of temporary forts facilitated the removal of a people from their ancestral lands.

- The resilience of both sides: The Seminoles’ tenacious defense of their home, and the soldiers’ often grim determination in an unfamiliar and hostile environment.

- The foundational struggles of early Florida settlers: The insecurity and danger that defined life on the frontier, and the critical role these forts played in providing a semblance of safety.

As the Suwannee River continues its journey to the Gulf, and the pines continue to sway, the spirit of Fort Houston lingers in the land. It is a silent reminder that history is not always found in the grand narratives or the preserved monuments, but often in the quiet, forgotten places. It’s in the unseen battlefields, the humble outposts, and the very soil beneath our feet that the most profound stories of human struggle and endurance are waiting to be rediscovered, ensuring that the echoes of the pine barrens continue to speak to us from the past.