Echoes in the Cypress: The Vanished World of Fort Lane, Florida

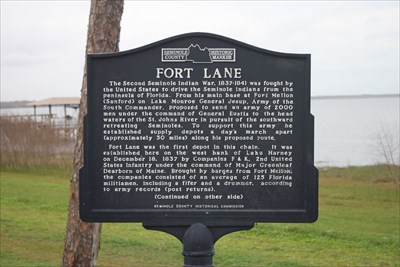

In the heart of Central Florida, where the ancient cypress knees stand sentinel along the shores of Lake Eustis, a quiet historical marker bears witness to a forgotten chapter of American history. It points to a location, now largely reclaimed by the persistent wilderness, that once thrummed with the desperate energy of a nation at war: Fort Lane. More than just a dot on a map, Fort Lane was a temporary bastion in a brutal conflict, a frontier outpost representing the fierce clash of cultures, the relentless march of expansion, and the enduring spirit of resistance that defined the Second Seminole War.

To understand Fort Lane is to delve into the very crucible of Florida’s identity, a period marked by profound violence, strategic ingenuity, and immense suffering on all sides. From 1835 to 1842, the United States Army waged its longest and costliest Indian war against the Seminole people, a confederation of Native Americans and African Americans who refused to abandon their ancestral lands for forced removal to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). It was a conflict born of land hunger, broken treaties, and a fundamental misunderstanding of sovereignty and cultural ties.

The U.S. government, fueled by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and the insatiable demand for cotton land, had enacted the Indian Removal Act of 1830. While many tribes in the southeastern United States were forcibly relocated, the Seminole, under dynamic leaders like Osceola, Micanopy, and Jumper, dug in their heels. Their resolve ignited a protracted guerrilla war across the dense, unforgiving landscape of Florida.

It was into this volatile environment that Fort Lane was born. Established around 1837-1838, it was one of a network of small, hastily constructed log-and-palisade forts designed to create a defensive perimeter, protect vital supply lines, and serve as staging points for military expeditions into the interior. Its strategic location near the western shore of Lake Eustis, then known as Lake Eustis, was crucial. The lake system provided a limited means of transport and communication, and the surrounding wilderness – a mosaic of cypress swamps, pine flatwoods, and scrub – was both a challenge to the U.S. forces and a sanctuary for the Seminole.

Life at Fort Lane was a grueling test of endurance. Imagine the scene: a crude stockade, perhaps 100 to 150 feet square, built from locally felled timber, its walls offering a fragile illusion of security against the unknown. Inside, a scattering of rough-hewn barracks, a commissary, a hospital tent, and a parade ground that quickly turned to mud with the incessant Florida rains. The air would have been thick with the smell of woodsmoke, damp earth, sweat, and the ever-present stench of mosquito repellent – likely crude concoctions of tar or animal fat.

Soldiers, a mix of U.S. Army regulars, state militia, and volunteers, often hailed from cooler climates and were ill-prepared for the subtropical crucible. The true enemy was often not just the elusive Seminole warrior but the environment itself. Malaria, yellow fever, dysentery, and other tropical diseases decimated the ranks. One historical account notes the devastating impact of disease, claiming more lives than enemy fire. As one anonymous soldier wrote in a letter home, describing conditions in a similar Florida fort, "This country is a perfect charnel house. Disease is more terrible than the Indians." The heat was oppressive, the humidity relentless, and the omnipresent insect swarms made every moment outside the palisade a torment.

For the men stationed at Fort Lane, days were a monotonous cycle of drills, guard duty, and the constant, nerve-wracking anticipation of an attack that might never come, or might come with devastating suddenness. Patrols ventured out into the wilderness, often returning exhausted, snake-bitten, and no closer to finding the Seminole, who moved through the terrain with unmatched stealth and knowledge. The dense vegetation and intricate waterways provided perfect cover for guerrilla tactics, allowing the Seminole to strike quickly and disappear without a trace.

Supply convoys, often moving by land or navigating the treacherous waterways, were prime targets. Securing these routes was a primary function of forts like Lane. Without regular provisions of food, ammunition, and medicine, these isolated outposts were untenable. The logistical challenges of sustaining a war in such an environment were immense, costing the U.S. government an astronomical sum – an estimated $20 million to $40 million, a staggering amount for the era, equivalent to billions today.

From the Seminole perspective, Fort Lane was a symbol of the encroaching threat, another encroachment on their sacred lands. Their strategy was not to hold ground but to harass, delay, and make the cost of the war so prohibitive that the Americans would eventually give up. They were fighting for their very existence, their culture, and their freedom. The swamps and hammocks were not just hiding places; they were their home, their pantry, their fortress. Their understanding of the land was their greatest weapon.

Osceola, though not directly associated with Fort Lane, epitomized this fierce resistance. His famous defiant act of plunging his knife into a treaty he believed fraudulent, declaring, "You have guns, and so have we… We will fight till the last drop of Seminole blood has moistened the dust of his hunting ground," resonated throughout the war. The Seminoles viewed the forts not as insurmountable obstacles but as targets of opportunity, or simply as points to be bypassed in their fluid, evasive warfare. They understood that the American military machine, while powerful, was slow and predictable in their environment.

While Fort Lane itself likely did not witness any major battles, it played a crucial, albeit unglamorous, role in the larger conflict. It contributed to the strategy of attrition, slowly wearing down both sides. It was part of the relentless pressure exerted on the Seminole, forcing them deeper into the Everglades, disrupting their hunting and planting, and eventually leading to their capture or surrender due to starvation and disease.

By 1842, the U.S. declared the war officially over, though a small number of Seminole never surrendered and remain in Florida to this day, a testament to their unbroken spirit. With the cessation of hostilities, forts like Lane quickly became obsolete. The soldiers moved on, and the Florida wilderness, with its astonishing regenerative power, began to reclaim what was once its own. Timber structures rotted, palisades collapsed, and the ground cover slowly obscured the traces of human habitation.

Today, little physical evidence of Fort Lane remains. The historical marker, placed by the Lake County Historical Society, is a silent sentinel, urging passersby to pause and reflect. It’s a testament to the ephemeral nature of human endeavors against the backdrop of time and nature. The exact footprint of the fort has likely been absorbed back into the landscape, a ghost in the cypress. Yet, its story, and the stories of countless similar forts across Florida, continues to echo.

Fort Lane stands as a powerful reminder of the complex, often tragic, narrative of American expansion. It represents the immense human cost of conquest, the courage of soldiers fighting in an alien environment, and the unyielding determination of an indigenous people fighting for their very survival. It forces us to confront the uncomfortable truths of our past: the forced removal policies, the environmental devastation, and the enduring legacy of conflict that shaped not only Florida but the nation.

The land around Lake Eustis today is dotted with vibrant communities, tourist attractions, and agricultural enterprises. But beneath the surface, for those willing to listen, the echoes of Fort Lane persist. They whisper in the rustling of the palmetto fronds, in the cries of the osprey over the lake, and in the deep, resonant silence of the cypress swamps. They remind us that history is not just about grand monuments and famous battles, but also about the forgotten outposts, the unseen struggles, and the quiet dignity of all those who lived and died in the pursuit of their deeply held beliefs. Fort Lane, though vanished, remains an integral, if spectral, part of Florida’s rich and complicated historical tapestry.