Okay, here is a 1,200-word article in a journalistic style about the history of the Apache Scouts in the U.S. Army.

The Ultimate Paradox: Apache Scouts and the Complex History of the American Frontier

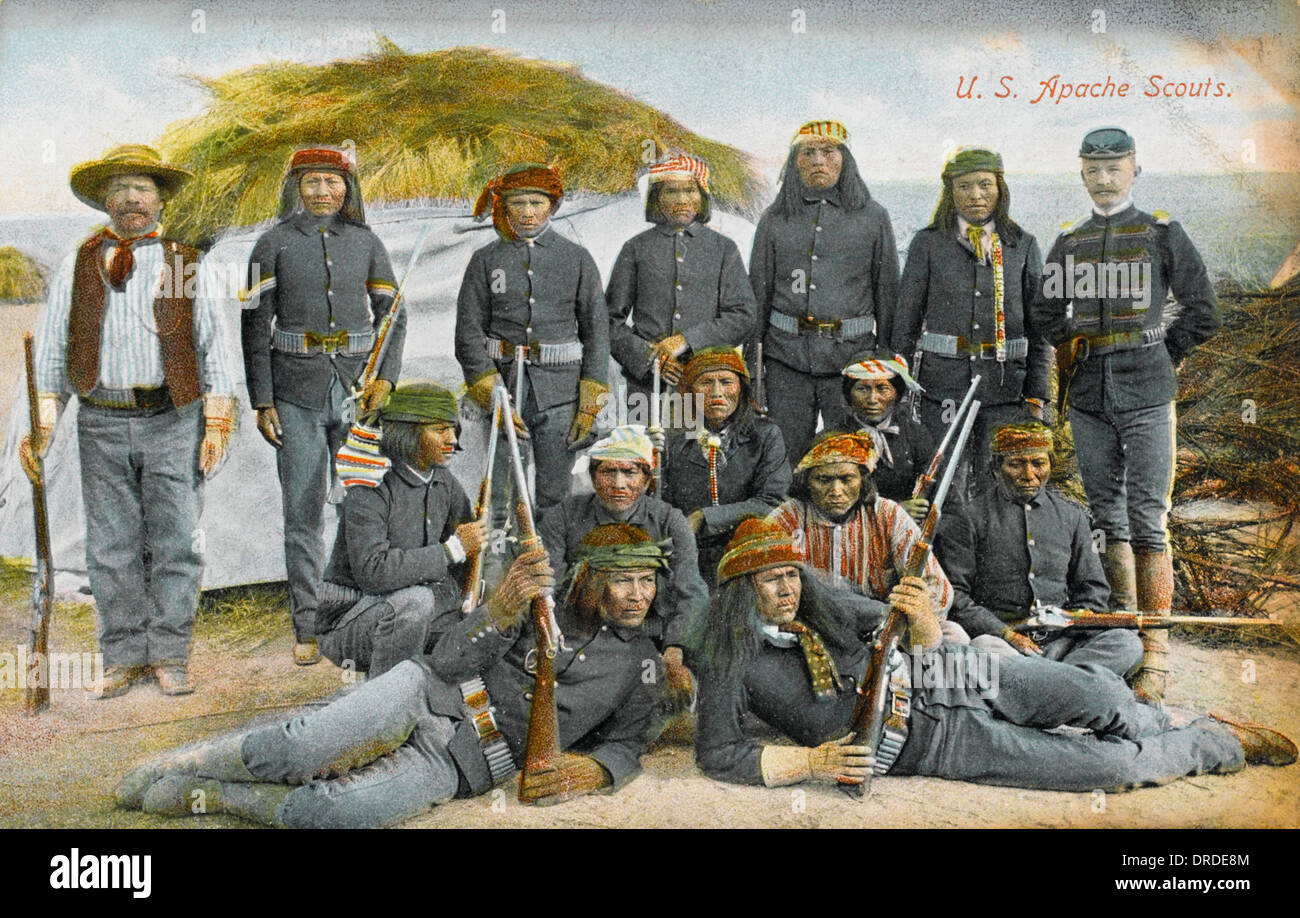

In the rugged, unforgiving landscapes of the American Southwest, where the sun beat down on unforgiving deserts and the Sierra Madre mountains clawed at the sky, a peculiar and profoundly impactful chapter of military history unfolded. It was a story woven from conflict, survival, and a stunning paradox: the enlistment of Apache warriors by the U.S. Army to hunt down and subdue their own people. These were the Apache Scouts, an indispensable, often overlooked, and deeply controversial force whose loyalty was perpetually tested, yet whose contribution proved decisive in the tumultuous era of the Indian Wars.

From the 1860s through the early 20th century, the U.S. Army found itself locked in a brutal, protracted struggle against various Apache bands – most famously, the Chiricahua led by figures like Cochise and Geronimo. The regular U.S. cavalry, trained for conventional warfare, was hopelessly outmatched by the Apaches’ intimate knowledge of the treacherous terrain, their legendary endurance, and their guerrilla tactics. Army columns were slow, conspicuous, and easily outmaneuvered. It was clear a new strategy was needed, one that borrowed from the very people they sought to defeat.

The idea of using "Indian Scouts" was not entirely new in American military history, but it reached its zenith and most complex expression with the Apache. The logic was simple yet profound: "It takes an Apache to catch an Apache." They knew the land, the language, the customs, the hiding places, and the fighting methods of their adversaries better than any white soldier ever could.

General Crook’s Visionary Approach

The most prominent advocate and user of Apache Scouts was General George Crook, often dubbed the "Gray Fox" for his cunning and his unconventional approach to warfare. Arriving in Arizona in 1871, Crook quickly realized the futility of conventional pursuit. He understood that to defeat the Apaches, he needed to integrate their strengths into his own forces. He began actively recruiting scouts, offering pay, rations, and the promise of protection for their families on the reservations.

Crook famously held a deep, if sometimes paternalistic, respect for the Apache. He dressed informally, sometimes riding ahead of his troops, and made efforts to understand their culture. His approach was radical for its time, and it paid dividends. He allowed the scouts to dress in their traditional attire, use their own weapons, and move with the stealth and speed that were their hallmarks. They were not merely guides; they were intelligence gatherers, trackers, and fierce combatants.

"I found them to be as faithful as any troops I ever commanded," Crook once remarked, "and I have been forced to admire their courage, their loyalty, and their keen intelligence." This trust was reciprocal to a degree. Many scouts genuinely respected Crook, seeing him as a man of his word, a rare quality among the often duplicitous white agents and officers they encountered.

The Paradox of Loyalty

But the decision for an Apache to become a scout was fraught with internal and external complexities. It was not a simple act of betrayal. Several factors motivated them:

- Inter-tribal Animosities: The Apache were not a monolithic entity. There were distinct bands (White Mountain, San Carlos, Cibecue, Chiricahua, etc.), and historical grievances and warfare existed between them long before the arrival of the Americans. Many scouts, particularly from the White Mountain and San Carlos bands, had suffered at the hands of renegade Chiricahua or other groups and saw alliance with the Army as a way to settle old scores or protect their own people.

- Survival and Security: For many, particularly those already settled on reservations, joining the scouts offered a means of survival. It provided regular pay (though meager, often $15-$25 a month plus rations), clothing, and a degree of security for their families at a time when traditional ways of life were rapidly eroding.

- Desire for Peace: Some scouts genuinely believed that helping the Army bring in the last holdouts would ultimately lead to a more stable and peaceful existence for all Apaches. They were weary of the endless cycle of violence.

- Status and Adventure: For young warriors, the scouts offered a path to distinction, adventure, and the opportunity to hone their skills in a new, albeit paradoxical, context.

Despite these motivations, scouts often found themselves caught between two worlds, navigating a treacherous path between their tribal identity and their military duty. They faced suspicion from both sides – seen as traitors by some of their own people and as untrustworthy "savages" by many white soldiers.

Unrivaled Skills and Key Campaigns

The Apache Scouts’ skills were legendary. They could track a single man across miles of rocky terrain, reading the subtle signs of disturbed earth, broken twigs, or displaced stones that were invisible to others. Their endurance was astounding; they could cover vast distances on foot or horseback, often subsisting on minimal rations. They were experts in camouflage, ambush, and close-quarters combat.

Their contributions were decisive in many key campaigns. The relentless pursuit of Geronimo and his small band of Chiricahua Apaches in the 1880s is perhaps the most famous example. General Nelson Miles, who replaced Crook, initially distrusted the Apache Scouts but soon came to rely on them. The final, grueling chase into Mexico’s Sierra Madre mountains, a landscape as formidable as any on earth, would have been impossible without them.

One pivotal moment came in March 1886, when Lieutenant Charles Gatewood, with a small contingent of soldiers and a larger, crucial group of Apache Scouts, finally located Geronimo’s camp deep in the mountains. It was the scouts, particularly men like Alchesay and Chato (a former renegade himself who had turned scout), who were instrumental in tracking Geronimo and later in convincing him to surrender. Their ability to speak Geronimo’s language and understand his mindset was critical where force had failed.

Notable Scouts and Their Legacies

Many individual Apache Scouts left their mark:

- Alchesay: A White Mountain Apache chief, he was a key advisor to General Crook and played a vital role in negotiating peace and persuading other Apaches to surrender. He was known for his diplomacy and leadership.

- Chato: Initially a Chiricahua war leader, Chato later became a scout after surrendering. His tracking skills and knowledge of Geronimo’s tactics were invaluable. He exemplified the complex journey many Apaches undertook.

- Mickey Free: A figure of myth and mystery, Mickey Free was an Apache-speaking boy of mixed Apache and Mexican heritage, abducted by Apaches as a child. He later became a scout, interpreter, and guide for the Army, known for his tracking abilities and his distinctive personality, including the loss of an eye in a knife fight.

These men, and hundreds of others whose names are less known, served with courage and often faced dangers from both sides of the conflict. They participated in engagements, often on the front lines, and suffered casualties alongside their white counterparts.

Beyond the Indian Wars

As the Indian Wars wound down by the late 19th century, the role of the Apache Scouts evolved. They continued to serve, often stationed at posts like Fort Huachuca in Arizona, which became a long-standing hub for their activities. They performed duties such as border patrol, tracking smugglers and outlaws, and maintaining order on reservations. Some even served in World War I, though their numbers significantly dwindled.

The official U.S. Army Indian Scout program was finally phased out in 1947, marking the end of a unique military tradition. The last Apache Scout, Sergeant William Alchesay (son of the previously mentioned Alchesay), died in 1957.

A Complex Legacy

The story of the Apache Scouts is a microcosm of the complex, often tragic, history of the American West. They were not simply collaborators or traitors, but pragmatic survivors navigating an existential crisis for their people. They fought bravely for the U.S. Army, a force that was simultaneously dismantling their traditional way of life. Their actions contributed to the "pacification" of the Apache people, leading to their confinement on reservations, but for many, it was also a path to protect their families, secure resources, and perhaps, ensure their cultural survival in a rapidly changing world.

Their legacy is a testament to resilience, adaptation, and the often-uncomfortable truths of history. They were the eyes and ears of the U.S. Army in a landscape that would have otherwise consumed it, and their skills were instrumental in shaping the final contours of the American frontier. The Apache Scouts remain a powerful symbol of the complex loyalties and profound ironies inherent in a nation forged on the contested lands of indigenous peoples. Their story reminds us that history is rarely black and white, but rather a rich, often contradictory, tapestry of human choices made in extraordinary circumstances.