The Hayfield Fight: A Fleeting Victory in the Nez Perce’s Desperate Bid for Freedom

In the vast, untamed expanse of Montana, where the rugged Absaroka Mountains claw at the sky and the Yellowstone River carves its ancient path, lies the silent stage of a lesser-known but strategically crucial engagement in the Nez Perce War of 1877. This was the Hayfield Fight, a swift and cunning maneuver by the beleaguered Nez Perce people that, for a precious moment, bought them time and hope in their epic flight for freedom. It stands as a testament to their ingenuity and the U.S. Army’s often-underestimated challenges in pursuing a determined and desperate foe across unforgiving terrain.

The summer of 1877 was a season of profound tragedy and desperate resolve for the Nez Perce. For months, bands led by revered chiefs like Looking Glass, White Bird, Ollokot, and the eloquent Chief Joseph had been on an agonizing journey, forced from their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley of Oregon and Idaho by the relentless pressure of white settlement and a broken treaty. Their objective was simple yet audacious: to escape to Canada, to find sanctuary with Sitting Bull’s Lakota, and to preserve their way of life beyond the reach of the U.S. government.

Their odyssey had already seen brutal skirmishes, most notably the devastating Battle of the Big Hole in early August, where hundreds of Nez Perce, many of them women and children, were massacred in a dawn attack by Colonel John Gibbon’s troops. Though the Nez Perce fought back fiercely, inflicting heavy casualties on the soldiers, the psychological toll was immense. Yet, they endured. Driven by an unyielding spirit, they continued their eastward trek, a testament to their resilience and the leadership of Chief Joseph, whose wisdom and strategic acumen would become legendary.

Following the Big Hole, the Nez Perce had vanished into the labyrinthine trails of the Bitterroot Mountains, traversing the treacherous Lolo Trail, a route General William Tecumseh Sherman famously called "one of the worst trails for man or beast on this continent." Their pursuers, primarily General Oliver O. Howard’s Department of the Columbia, were a mix of exhausted regulars, volunteers, and Bannock scouts, struggling with the same rugged landscape, logistical nightmares, and the sheer elusiveness of their quarry. Howard, nicknamed "Old One-Arm" for a wound sustained during the Civil War, was a tenacious but often frustrated commander.

As August drew to a close, the Nez Perce, numbering around 700-800 souls—with only about 200 effective warriors—were nearing the eastern edge of what is now Yellowstone National Park. Their route lay through the rugged Absaroka Range, and their ultimate goal was the Canadian border, still hundreds of miles to the north. But blocking their potential paths was a fresh contingent of U.S. cavalry: Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis and his 7th U.S. Cavalry, the same regiment that had suffered Custer’s catastrophic defeat the previous year at the Little Bighorn. Sturgis, keen to restore the regiment’s tarnished reputation, had been ordered by General Howard to intercept the Nez Perce, specifically to block their exit from the mountains into the open plains of Montana.

Sturgis, with approximately 350 men, had positioned his troops strategically along the Clark’s Fork and Stinkingwater (now Shoshone) rivers, anticipating the Nez Perce would emerge through the most obvious mountain passes. He was confident, perhaps overly so, that he had effectively sealed off their escape. "I had every pass and trail guarded," Sturgis later reported, "and felt sure of heading them off."

However, Sturgis made a critical miscalculation. He underestimated the Nez Perce’s intimate knowledge of the land, their desperate ingenuity, and their skill in reconnaissance. While Sturgis waited in the passes, the Nez Perce, under the guidance of skilled scouts like Lean Elk, identified an alternative route: a less obvious, but traversable, path around Sturgis’s positions, through the rugged Clark’s Fork Canyon.

On August 20th, 1877, as the Nez Perce began their flanking movement, their scouts observed a crucial vulnerability in Sturgis’s lines. The U.S. cavalry had established a temporary hayfield near the mouth of the Clark’s Fork Canyon, where soldiers were busy cutting and stacking hay for their horses and mules. This hay was not just fodder; it represented the very mobility of the cavalry. Without it, their horses would weaken, and their pursuit would grind to a halt. More importantly, these hay wagons, guarded by a relatively small detachment of soldiers, were isolated and presented a tempting target.

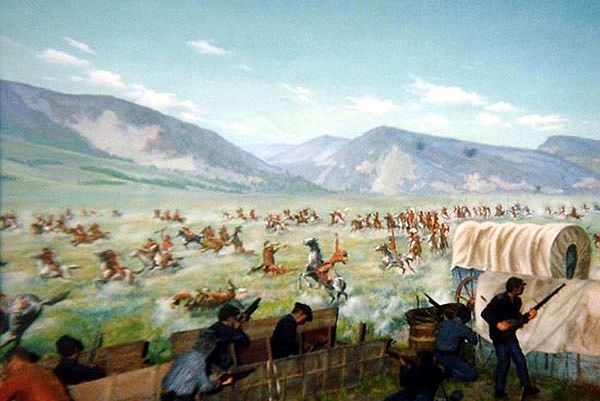

The Nez Perce, ever opportunistic, saw their chance. They didn’t seek a pitched battle; they sought distraction, supplies, and most critically, to buy time for their main body, including the women, children, and elderly, to slip past Sturgis’s main force. A small band of Nez Perce warriors, perhaps no more than 30-50, initiated a daring raid.

With characteristic speed and stealth, they descended upon the hayfield. The attack was swift and brutal. The soldiers guarding the hay were completely surprised. In the ensuing chaos, the Nez Perce managed to stampede a significant number of the army’s horses and mules. They set fire to the freshly cut hay, sending plumes of smoke billowing into the clear Montana sky—a signal of their presence, but also a diversion.

The fight itself was not a prolonged engagement in terms of direct combat. Casualties were remarkably light, particularly for the Nez Perce, who suffered none. The U.S. Army reported one scout wounded and a few mules killed. The objective was not to annihilate the enemy but to disrupt, demoralize, and acquire resources. The Nez Perce succeeded on all counts. They captured some horses, invaluable for their arduous journey, and effectively destroyed a vital supply for Sturgis’s command.

Colonel Sturgis, hearing the distant gunfire and seeing the smoke, quickly dispatched troops to investigate. By the time his main force arrived, however, the Nez Perce warriors had accomplished their mission and vanished back into the rugged canyons, melting away as silently as they had appeared. Sturgis’s frustration must have been palpable. Not only had his carefully laid trap been bypassed, but his command had been outmaneuvered and deprived of crucial supplies by a group he was supposed to be containing.

The Hayfield Fight, while a minor skirmish in terms of casualties, was a significant tactical victory for the Nez Perce. It solidified their escape from Sturgis’s intended ambush and further complicated the army’s pursuit. It bought them valuable time, allowing the main body of the Nez Perce to continue their arduous trek eastward, through the geysers and thermal features of Yellowstone National Park, leaving a trail of bewildered tourists and frustrated soldiers in their wake.

For Sturgis, the incident was a humiliating setback. His cavalry, now without fresh hay, was further hampered in its ability to pursue. The delay allowed the Nez Perce to widen the gap between themselves and their pursuers. General Howard, whose troops were still lagging behind, eventually linked up with Sturgis, bringing a much-needed increase in numbers but also the added baggage of logistical challenges.

The Hayfield Fight also underscored the stark contrast in the motivations and methods of the two sides. For the U.S. Army, it was a campaign of pacification, of enforcing government policy and treaty obligations, however unjust they might have been. For the Nez Perce, it was a desperate fight for survival, a testament to their inherent right to self-determination. Their tactics were not those of conventional warfare but of evasion, resourcefulness, and exploiting the weaknesses of a larger, better-equipped, but often less agile, foe.

The legacy of the Hayfield Fight, like many such engagements in the Nez Perce War, is one of human endurance and the high cost of conflict. It’s a reminder of the strategic brilliance and unwavering spirit of a people fighting for their freedom against overwhelming odds. While the Nez Perce would eventually be cornered and forced to surrender at Bear Paw Mountain just weeks later, their flight across 1,170 miles of unforgiving terrain, punctuated by moments of cunning defiance like the Hayfield Fight, remains one of the most remarkable military retreats in American history.

Today, the site of the Hayfield Fight is unmarked, blending back into the vast, wild landscape of Montana. Yet, the echoes of that brief, desperate struggle persist, a silent monument to the Nez Perce’s ingenuity and their enduring fight for a homeland they would ultimately never reclaim. It’s a chapter in American history that reminds us that even in the shadow of defeat, moments of defiance can shine brightly, illuminating the indomitable spirit of those who fought for their very existence.