The Shadow of Compromise: How the Missouri Deal Tried to Save America, and Only Delayed its War

In the early months of 1820, America teetered on the precipice of a crisis that threatened to unravel the young republic. The "Era of Good Feelings," a period of relative political unity and national pride following the War of 1812, was about to be shattered by a single, explosive question: could slavery expand into the vast new territories acquired through the Louisiana Purchase? The admission of Missouri to the Union, an seemingly mundane administrative task, ignited a fierce sectional conflict that would be temporarily quelled by the legislative masterpiece known as the Missouri Compromise. Yet, this fragile truce, born of necessity and political maneuvering, ultimately served not as a permanent solution, but as a chilling premonition of the nation’s inevitable reckoning.

To understand the profound significance of the Missouri Compromise, one must first grasp the delicate balance that existed within the United States Congress. By 1819, the Union comprised twenty-two states, evenly split between eleven free states and eleven slave states. This parity ensured that in the Senate, where each state held two votes regardless of population, neither side could unilaterally pass legislation favoring its interests, particularly on the contentious issue of slavery. The House of Representatives, with its representation based on population, generally leaned towards the free states due to their larger and growing populations, but the Senate remained the crucial battleground.

When Missouri, a territory carved out of the Louisiana Purchase, applied for statehood, it presented a formidable challenge to this precarious equilibrium. Settlers in Missouri, many of whom had migrated from southern states, had brought enslaved people with them, and the proposed state constitution allowed for slavery. Its admission as a slave state would tip the balance in the Senate, giving the South a powerful, and potentially unassailable, majority on any slavery-related issue.

The ensuing debate was not merely about political power; it was a deeply moral and economic struggle that laid bare the fundamental schism within the American experiment. On February 13, 1819, James Tallmadge Jr., a New York Congressman, introduced an amendment to the Missouri statehood bill. The "Tallmadge Amendment" proposed two key provisions: first, no more enslaved people could be brought into Missouri; and second, all children born to enslaved parents in Missouri after its admission to the Union would be set free at the age of twenty-five.

The reaction was immediate and ferocious. Southern representatives viewed the amendment as a dangerous precedent, an unconstitutional intrusion by the federal government into the domestic institutions of a state, and a direct threat to their economic system, which was increasingly reliant on enslaved labor, especially with the booming cotton industry in the South. They argued that Congress had no right to dictate the internal affairs of a sovereign state and that such a move would pave the way for federal abolition of slavery everywhere.

Northern representatives, many driven by nascent abolitionist sentiments or a desire to curb the spread of slavery, applauded Tallmadge’s stance. They argued that Congress had the power to set conditions for the admission of new states, as evidenced by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which had prohibited slavery in territories north of the Ohio River. They saw the vast Louisiana Purchase as an opportunity to prevent the expansion of what they increasingly viewed as a moral blight.

The debate raged for months. Passions ran so high that some even spoke openly of disunion. Thomas Jefferson, then in his retirement at Monticello, famously described the crisis in an 1820 letter to John Holmes: "This momentous question, like a firebell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union." Jefferson, despite owning enslaved people himself, recognized the inherent danger of a geographic division over slavery, predicting it would eventually lead to a "line of separation."

The Tallmadge Amendment passed in the House of Representatives, largely due to the North’s numerical superiority, but it was decisively defeated in the Senate, where the even balance of power allowed Southern votes to block it. The 15th Congress adjourned without resolving the Missouri question, leaving the nation in a state of anxious limbo.

When the 16th Congress convened in December 1819, the crisis had only deepened. The issue was further complicated by Maine, then a district of Massachusetts, applying for statehood as a free state. This provided a critical opening for compromise. Into this highly charged atmosphere stepped Henry Clay of Kentucky, the Speaker of the House, a master of legislative strategy and a fervent believer in the Union. Nicknamed "The Great Compromiser," Clay possessed an uncanny ability to forge consensus out of seemingly intractable disputes.

Clay, along with other key figures like Senator Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois, orchestrated a series of legislative maneuvers that would become known as the Missouri Compromise. The core components of this intricate deal were:

- Missouri’s Admission as a Slave State: To appease the South and maintain the principle that new states could choose their own institutions, Missouri would be admitted to the Union as a slave state.

- Maine’s Admission as a Free State: To restore the delicate balance in the Senate, Maine would be admitted as a free state, thus preserving the 12-12 split. This was a crucial quid pro quo for the North.

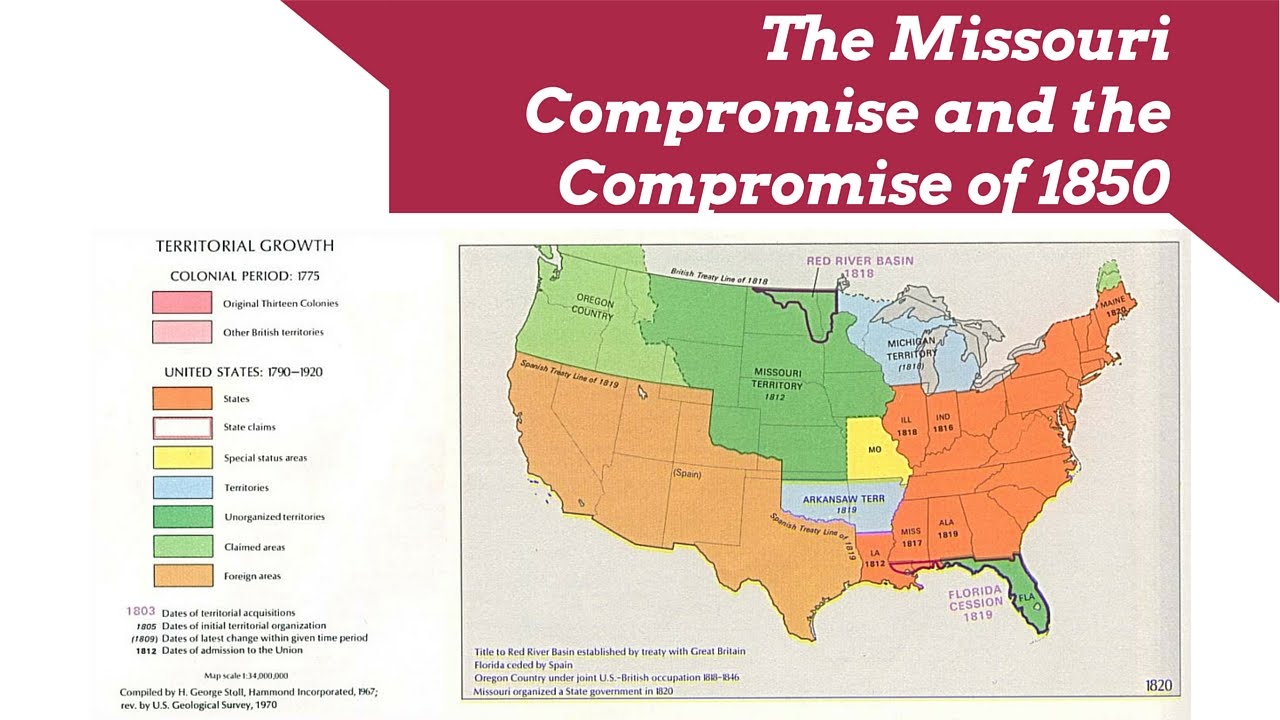

- The 36°30′ Parallel Line: Most significantly, the compromise established a geographical dividing line for the remainder of the Louisiana Purchase territory. With the exception of Missouri itself, slavery would be forever prohibited in all future states formed from the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36°30′ north latitude line. South of this line, slavery would be permitted.

This final provision was the true heart of the compromise, attempting to draw a clear boundary that would prevent future disputes over slavery’s expansion. It was a bold assertion of federal power to regulate slavery in the territories, a power that many Southerners had vociferously denied during the Tallmadge debates.

The Compromise passed Congress in March 1820, with President James Monroe reluctantly signing it into law. Monroe, like Jefferson, had private reservations about the constitutionality of the federal government dictating slavery in the territories, but he ultimately prioritized national unity. The news of its passage was met with a collective sigh of relief across the nation. The immediate threat of disunion had been averted, and the "firebell" had been temporarily silenced.

However, the relief was short-lived. A new hurdle emerged when Missouri’s proposed state constitution included a clause that prohibited the entry of "free negroes and mulattoes" into the state. This clause was seen by many Northerners as a violation of the "privileges and immunities" clause of the U.S. Constitution, which guaranteed equal treatment to citizens of all states. For a moment, it seemed the entire compromise might unravel.

Once again, Henry Clay stepped in. He engineered a "Second Missouri Compromise" in 1821, securing Missouri’s admission on the condition that its legislature would never pass any law that violated the rights of any U.S. citizen. While the actual impact of this provision was debatable and rarely enforced, it provided enough political cover for Northern representatives to accept Missouri’s constitution, and the state finally joined the Union in August 1821.

The Missouri Compromise bought the nation thirty-four years of relative peace on the issue of slavery’s expansion. It postponed the inevitable, but it did not, and could not, resolve the fundamental conflict. It established a precedent of federal intervention in territorial slavery, but also implicitly acknowledged the right of states to choose slavery within their borders. More importantly, it enshrined the idea of a geographical division, fostering a growing sense of "sectionalism" – a primary loyalty to one’s region rather than to the nation as a whole.

The seeds of future conflict were sown even as the compromise was celebrated. The moral argument against slavery continued to gain strength in the North, fueled by the rise of abolitionist movements. Meanwhile, the South became increasingly defensive of its "peculiar institution," viewing any restriction on its expansion as an existential threat. The Louisiana Purchase was followed by further territorial acquisitions, particularly from the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), which opened up vast new lands in the West, once again raising the explosive question of slavery’s status.

The Compromise of 1850, another complex legislative package, attempted to address these new territorial disputes, but it too proved to be a temporary balm. The ultimate undoing of the Missouri Compromise came in 1854, with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, championed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. This act explicitly repealed the 36°30′ line, asserting the principle of "popular sovereignty," which allowed the residents of Kansas and Nebraska territories to decide for themselves whether to permit slavery.

The repeal of the Missouri Compromise ignited a firestorm. It was seen by many Northerners as a betrayal, a cynical capitulation to Southern demands, and an open invitation for slavery to spread across the entire continent. The result was "Bleeding Kansas," a period of violent conflict between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, serving as a brutal dress rehearsal for the Civil War.

The Missouri Compromise, therefore, stands as a pivotal moment in American history. It was a triumph of political pragmatism, a testament to Henry Clay’s unparalleled ability to navigate treacherous legislative waters, and it undeniably saved the Union from fracturing in 1820. Yet, its legacy is deeply complex. It papered over, rather than healed, the nation’s deepest wound. By establishing a clear geographical line, it inadvertently reinforced the very sectional divisions it sought to manage. It taught future generations that while compromise could avert immediate disaster, fundamental moral issues, particularly those touching on human rights and economic systems, could only be delayed, not permanently suppressed. The "firebell in the night" had rung, and though its echoes faded for a time, its final, cataclysmic peal would come just four decades later.