Bleeding Kansas: The Unholy Alliance of Slavery’s Defenders and the Crucible of a Nation Divided

In the mid-19th century, the vast, windswept plains of Kansas became an unlikely crucible for the soul of a nation. Far from the bustling cities of the East, a brutal, localized civil war erupted, fueled by a fundamental question: would slavery expand into new territories, or would it be forever confined? This period, infamously known as "Bleeding Kansas," was not merely a series of skirmishes; it was a violent, premeditated campaign by pro-slavery forces to seize control of the territory and ensure its future as a slave state, a chilling prelude to the American Civil War.

The roots of this conflict lie in the fateful year of 1854, with the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Championed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, the Act aimed to organize the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, facilitating the construction of a transcontinental railroad. However, its most contentious provision was the principle of "popular sovereignty," which decreed that the residents of these territories, rather than Congress, would decide whether to allow slavery within their borders. This seemingly democratic solution was a bombshell, as it explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, thus opening up vast new lands to the institution.

For the pro-slavery movement, this was an unprecedented opportunity. The Southern states, increasingly feeling besieged by abolitionist sentiment and outnumbered in the House of Representatives, saw Kansas as a vital battleground. Securing Kansas for slavery would not only expand their economic and political power but also serve as a bulwark against the perceived encroachment of free-state ideals. Their strategy was clear: flood the territory with pro-slavery settlers, dominate the electoral process, and establish a government that would enshrine slavery in law.

The Border Ruffians: A Premeditated Invasion

The immediate and most aggressive manifestation of the pro-slavery campaign came from Missouri, Kansas’s eastern neighbor. Missouri was a slave state, and its residents, particularly those along the border, viewed the prospect of a free Kansas with alarm. They feared that a free Kansas would become a haven for runaway slaves, undermine the value of their human property, and eventually threaten the very existence of slavery in Missouri itself. These zealous pro-slavery Missourians, dubbed "Border Ruffians" by the press, became the shock troops of the movement.

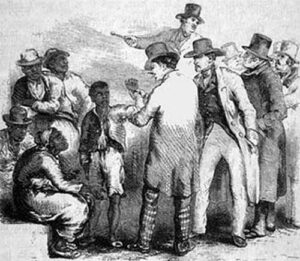

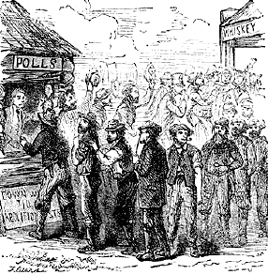

Their tactics were anything but democratic. When the first territorial elections were held, particularly for the territorial legislature in March 1855, thousands of armed Border Ruffians poured across the border. They cast illegal ballots, often without even residing in Kansas, intimidating legitimate free-state voters and stuffing ballot boxes. One contemporary account estimated that more than 6,300 votes were cast, despite there being only around 2,900 eligible voters in the territory. David R. Atchison, a U.S. Senator from Missouri and a fervent advocate for slavery, openly encouraged these actions. He famously declared that if necessary, they would "kill every God-damned abolitionist in the district."

The result was a sham election that installed a vehemently pro-slavery legislature, headquartered in Lecompton. This "Bogus Legislature," as free-staters called it, immediately set about cementing slavery’s hold on Kansas. They enacted a series of draconian laws designed to suppress any anti-slavery sentiment: it became a capital offense to aid a runaway slave, a felony to question the legality of slavery in Kansas, and even a crime to possess or circulate anti-slavery literature. These laws made it virtually impossible for free-staters to express their views or organize politically without risking severe penalties.

The Free-State Counter-Movement and Escalation

Naturally, free-state settlers, many of whom had migrated from New England with the express purpose of making Kansas free, refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Lecompton government. Organizations like the New England Emigrant Aid Company actively encouraged and financed the migration of anti-slavery settlers, providing them with tools, supplies, and even Sharps rifles, which became known as "Beecher’s Bibles" (after Henry Ward Beecher, a prominent abolitionist who raised funds for them).

In defiance of the Lecompton legislature, free-staters established their own provisional government in Topeka, drafting an anti-slavery constitution. Kansas now had two rival governments, two rival legal systems, and two deeply antagonistic populations, setting the stage for inevitable violence.

The first major eruption of violence occurred in May 1856. Following the indictment of several free-state leaders for treason by a pro-slavery grand jury, Sheriff Samuel J. Jones, a staunch pro-slavery advocate, led a force of some 800 Border Ruffians and other pro-slavery militia into the free-state stronghold of Lawrence. On May 21, 1856, they sacked the town, destroying newspaper offices, burning the Free-State Hotel, and looting homes. Though only one life was lost (a pro-slavery man killed by falling debris), the "Sack of Lawrence" was a symbolic act of aggression, demonstrating the pro-slavery movement’s willingness to use overwhelming force to crush dissent.

John Brown and the Cycle of Retribution

The events in Lawrence ignited a fuse. Just days later, on the night of May 24-25, 1856, a radical abolitionist named John Brown, convinced he was an instrument of God’s wrath, retaliated with brutal efficiency. Along with his sons and other followers, Brown dragged five unarmed pro-slavery settlers from their homes along Pottawatomie Creek and hacked them to death with broadswords. The Pottawatomie Massacre was a horrific act of cold-blooded murder, but it transformed Bleeding Kansas from a political struggle into an open, bloody guerrilla war.

The cycle of violence escalated rapidly. Pro-slavery militias and free-state "Jayhawkers" roamed the territory, raiding settlements, ambushing travelers, and engaging in pitched battles. Towns like Osawatomie and Marais des Cygnes became sites of further massacres and skirmishes. Homes were burned, crops destroyed, and families terrorized. The territory descended into anarchy, with estimates of casualties ranging into the hundreds over the next few years. The pro-slavery forces, initially driven by a desire for political control, now also sought vengeance for the attacks on their own.

National Implications and the Lecompton Constitution

The turmoil in Kansas resonated deeply across the nation, exposing the fragility of the Union. The violence in Kansas even spilled into the halls of Congress when, also in May 1856, South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks brutally assaulted Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner with a cane on the Senate floor. Sumner had delivered a fiery anti-slavery speech titled "The Crime Against Kansas," in which he personally attacked Brooks’s cousin, Senator Andrew Butler, a pro-slavery advocate. Brooks’s act was celebrated in the South and condemned in the North, further widening the chasm between the two sections.

The pro-slavery movement’s most ambitious political maneuver was the drafting of the Lecompton Constitution in 1857. This constitution was designed to ensure Kansas would enter the Union as a slave state. Its most egregious clause protected slave property already in the territory and prohibited any future legislature from emancipating slaves. In a cynical attempt to appear democratic, the constitution was put to a vote, but voters were only given two options: vote for the constitution "with slavery" or "with no slavery." Even the "no slavery" option protected existing slave property. Free-staters, recognizing the fraud, largely boycotted the vote, allowing the pro-slavery faction to "approve" the constitution.

President James Buchanan, a Democrat with strong Southern sympathies, controversially endorsed the Lecompton Constitution and urged Congress to admit Kansas as a slave state. This move sparked a furious debate in Washington, dividing the Democratic Party and alienating powerful figures like Stephen A. Douglas, who recognized the blatant disregard for popular sovereignty. Douglas, despite being the architect of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, could not stomach such a transparently fraudulent process. Congress ultimately rejected the Lecompton Constitution, a significant setback for the pro-slavery movement’s efforts to manipulate the territory’s destiny.

The End of the Struggle (for Kansas)

The struggle in Kansas continued, albeit with declining intensity, until the eve of the Civil War. By 1859, free-state settlers significantly outnumbered their pro-slavery counterparts, thanks to continued migration from the North and the disillusionment of many pro-slavery settlers with the constant violence and political instability. A new, genuinely anti-slavery constitution, the Wyandotte Constitution, was drafted and ratified by a clear majority of Kansas voters.

When Southern states began seceding from the Union in late 1860 and early 1861, the political landscape shifted dramatically. With Southern opposition to Kansas’s admission as a free state removed, Kansas finally entered the Union as a free state on January 29, 1861. The long, bloody battle for Kansas was over, but its scars ran deep.

Legacy of Bleeding Kansas

"Bleeding Kansas" was more than just a territorial dispute; it was a microcosm of the national crisis. The pro-slavery movement’s aggressive tactics – electoral fraud, legislative tyranny, and outright violence – demonstrated their unwavering commitment to expanding and protecting the institution of slavery, even at the cost of democratic principles and human lives. Their actions radicalized the anti-slavery movement, leading to figures like John Brown, and pushed the nation ever closer to the brink.

The events in Kansas exposed the fundamental incompatibility of popular sovereignty with the deeply entrenched moral and economic divisions over slavery. It proved that in the face of such profound ideological conflict, peaceful democratic processes could break down, replaced by brute force and the rule of the gun. The plains of Kansas, drenched in the blood of settlers fighting for their vision of America, became a training ground and a dress rehearsal for the larger, more devastating Civil War that would engulf the entire nation just months after Kansas achieved statehood. The unholy alliance of slavery’s defenders had, ironically, helped to forge the very conditions for its eventual demise.