The Frozen Lure: How the Klondike Gold Rush Forged a Legend of Greed, Grit, and Golden Dreams

On a sweltering July day in 1897, when the steamship Excelsior docked in San Francisco, followed swiftly by the Portland in Seattle, their holds laden with over two tons of Klondike gold, a spark ignited across America. That spark quickly became a wildfire, consuming the hopes and dreams of a generation. The headlines screamed: "Gold! Gold! Gold! 68 Rich Men on the Steamer Portland!" and "A Ton of Gold!" In an instant, the drab realities of economic depression and urban monotony were overshadowed by the dazzling promise of instant wealth in the remote, frozen wilderness of the Canadian Yukon. This was the Klondike Gold Rush, an epic human migration that would test the limits of endurance, define the spirit of adventure, and etch an indelible mark on history.

The story truly began almost a year earlier, on August 16, 1896, when George Carmack, a white prospector, along with his Tagish First Nation relatives Skookum Jim Mason and Dawson Charlie (Keish), made a fateful discovery on Rabbit Creek (renamed Bonanza Creek) in the Klondike region. While the exact details of who found the first nugget are debated, the result was undeniable: an astonishingly rich gold strike. News trickled out slowly at first, but by the time the Excelsior and Portland arrived with their gleaming cargo, the dam burst. Lawyers left their practices, farmers abandoned their fields, doctors closed their clinics, and shopkeepers locked their doors. An estimated 100,000 people from all walks of life, driven by a potent cocktail of desperation, ambition, and a thirst for adventure, dropped everything to chase the golden dream.

The journey to the Klondike was, in itself, an odyssey of biblical proportions. The vast majority of stampeders, as they came to be known, headed to the Alaskan ports of Skagway or Dyea. From there, two main routes lay ahead, each a brutal gauntlet designed to break the spirit and body: the Chilkoot Trail and the White Pass Trail.

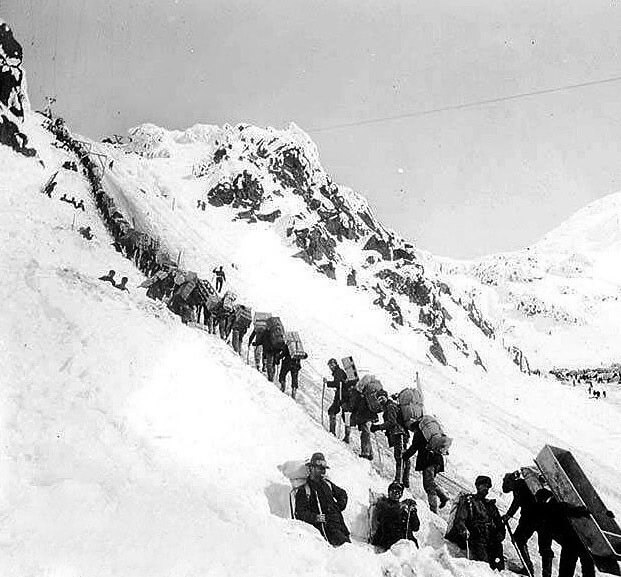

The Chilkoot, often called the "Poor Man’s Route," was a steep, treacherous ascent over a mountain pass. Before prospectors could even begin, the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) enforced a strict, life-saving regulation: each individual was required to carry a year’s supply of food and equipment – approximately one ton of goods. This was to prevent starvation in the isolated Klondike. For those tackling the Chilkoot, it meant an agonizing series of "relays." A prospector would carry a 50-pound pack a few miles, drop it, return for another, and repeat the process countless times. The most infamous section was the "Golden Stairs," a near-vertical 1,500-foot climb over loose rock and ice, where a continuous line of tiny human figures, resembling ants, slowly inched their way upwards, often cutting steps into the frozen snow. It could take weeks, even months, to move one’s entire ton of supplies over the pass.

A contemporary account vividly described the scene: "The trail was a solid mass of men, dogs, and horses, moving slowly, painfully, to the summit. The air was filled with curses, the crack of whips, and the moans of suffering animals." The sheer physical and mental toll was immense. Many simply gave up, their dreams shattered before they even reached the Yukon River.

The White Pass, or "Dead Horse Trail," offered an alternative, but no less harrowing, path. While less steep, it was even more unforgiving for pack animals. The narrow, muddy, boulder-strewn trail became a graveyard for thousands of horses, whose carcasses lined the route, creating a horrific stench and a grim reminder of the journey’s dangers. It was here that infamous figures like Jefferson "Soapy" Smith, a notorious con artist, plied their trade in the lawless town of Skagway, preying on the naive and desperate.

Once over the passes, prospectors faced another challenge: navigating hundreds of miles of treacherous rivers and lakes, building crude boats or rafts, before reaching the Yukon River, which would carry them the final distance to Dawson City. This entire journey, from coastal Alaska to the heart of the Klondike, could take six months to a year, pushing the limits of human endurance, resilience, and sanity.

Dawson City itself was a marvel of human ingenuity and desperation, a boomtown that sprang up almost overnight at the confluence of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers. In 1896, it was a small fishing camp; by 1898, its population swelled to an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 people, making it the largest city north of San Francisco and west of Winnipeg. It was a chaotic, vibrant, and expensive place. Prices for basic goods were exorbitant: eggs sold for a dollar each, a loaf of bread for 50 cents, and a single potato for a quarter – all luxuries in a land where fresh produce was almost non-existent.

Despite the rapid growth and influx of diverse characters, Dawson City was remarkably orderly, thanks in large part to the omnipresent North-West Mounted Police. Unlike the wilder American gold rush towns, the NWMP maintained a strong presence, ensuring a semblance of law and order that often surprised newcomers. Their strict enforcement of rules and their visible authority deterred much of the overt lawlessness typically associated with such boomtowns.

Life in Dawson was a fascinating microcosm of late 19th-century society. Saloons, gambling dens, and dance halls operated around the clock, offering fleeting distractions from the cold and the arduous work. Entrepreneurs of all stripes flocked to the city, recognizing that the real money wasn’t necessarily in digging for gold, but in selling shovels, provisions, and services. Nellie Cashman, "the Angel of the Klondike," was one such figure, a shrewd businesswoman and philanthropist who ran boarding houses and staked claims, earning a reputation for her generosity.

However, the reality of striking it rich was far grimmer than the sensational headlines suggested. For every lucky prospector who found a bonanza claim, thousands toiled in vain, their hopes slowly eroding in the frozen earth. Gold mining in the Klondike was incredibly difficult. The gold lay buried under thick layers of permafrost, requiring prospectors to build fires to thaw the ground, then dig down to the pay dirt, often working in cramped, dark, and dangerous conditions.

One of the most enduring legacies of the Klondike Gold Rush comes from those who experienced its harsh realities. The celebrated American author Jack London, though he never struck it rich, spent a winter in the Klondike and drew heavily on his experiences for some of his most famous works, including "The Call of the Wild" and "White Fang." His stories immortalized the brutal beauty of the Yukon wilderness and the indomitable spirit of those who dared to challenge it. London’s personal account echoes the sentiments of many: "The Klondike was a school where I learned a great deal about men, and a great deal about myself."

By 1899, the Klondike Gold Rush was effectively over. New gold strikes in Nome, Alaska, diverted the flow of stampeders, and many of the original claims in the Klondike began to play out. The population of Dawson City plummeted, leaving behind a testament to a fleeting, frenzied dream.

In total, an estimated $50 million in gold (worth billions in today’s currency) was extracted from the Klondike, but the human cost was immeasurable. Thousands endured unimaginable hardship, and many lost their lives to accident, disease, or starvation. Yet, the Klondike Gold Rush remains more than just a chapter in economic history; it is a powerful allegory for the human spirit. It speaks to our innate desire for opportunity, our willingness to endure extreme suffering for the promise of a better life, and the enduring allure of the unknown.

Today, the Chilkoot Trail is a national historic site, traversed by hikers seeking to retrace the steps of the stampeders. Dawson City, though much smaller, preserves its historic buildings and offers a glimpse into its golden past. The Klondike Gold Rush stands as a monument to a pivotal moment when the world turned its gaze northward, drawn by the irresistible glitter of gold, forever changing the landscape of the Yukon and the dreams of a generation. It was a time when the boundaries of human endurance were pushed to their absolute limits, forging legends out of ordinary people and reminding us that sometimes, the greatest treasures are not found in the ground, but within ourselves.