The Gilded Cage: Shady Ladies and the Untamed Soul of the Klondike Gold Rush

The name Klondike conjures images of rugged men, pickaxes glinting under the Arctic sun, and the relentless pursuit of glittering gold. It speaks of unforgiving trails, frozen rivers, and the wild, untamed spirit of the late 19th-century frontier. But amidst the clamor of a thousand hopeful prospectors, a less-told, equally compelling narrative belongs to the "shady ladies" – the dance hall girls, the madams, the prostitutes, and the entertainers who flocked to the remote Yukon Territory. They were women who traded on desire, comfort, and companionship in a world built almost exclusively by men, for men, and in doing so, became an indispensable, if often maligned, part of the Klondike’s pulsating, chaotic heart.

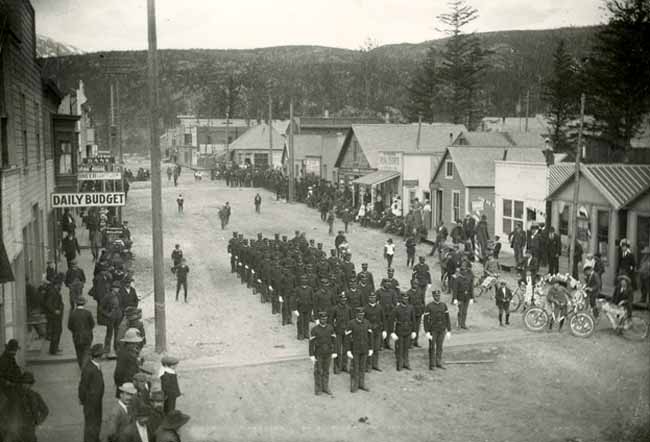

The Klondike Gold Rush, ignited by George Carmack’s discovery in 1896, was a phenomenon of unprecedented scale and hardship. Tens of thousands left everything behind, braving the treacherous Chilkoot or White Pass trails, hauling a year’s worth of supplies over mountains of ice and rock. They arrived in Dawson City, a boomtown that sprang up almost overnight at the confluence of the Yukon and Klondike rivers, a place where fortunes were made and lost in the blink of an eye. This was a land of extremes: extreme wealth, extreme poverty, extreme cold, and an extreme gender imbalance. For every woman in Dawson, there were, by some estimates, ten to twenty men. This demographic reality created a unique economic ecosystem, one in which female company, in any form, became a commodity of immense value.

The "shady ladies" were not a monolith. Their ranks included desperate women fleeing poverty or scandal, ambitious entrepreneurs seeking to capitalize on the boom, and seasoned professionals who saw the Klondike as the ultimate market for their services. They arrived by the same arduous routes as the men, often enduring equal or greater hardship, but with a different kind of ambition in their hearts. They were not seeking gold in the gravel, but in the pockets of the men who had found it, or hoped to.

At the highest tier of the "shady" social ladder were the dance hall girls and entertainers. Establishments like the Flora Dora and the Monte Carlo in Dawson City were the pulsating heart of the town’s social life. Here, women in elaborate gowns, often sourced from San Francisco or Seattle at exorbitant prices, would dance with prospectors, offering a fleeting moment of intimacy and glamour. A single dance ticket could cost a dollar – a significant sum at the time – and a girl might earn hundreds in an evening. Their job was not just to dance, but to encourage men to buy overpriced drinks, known colloquially as "short beers," from which they received a commission. These women, often skilled at conversation and flirtation, provided a vital psychological service in a lonely, isolated frontier. They offered a semblance of civilization, a distraction from the back-breaking labor and the relentless pursuit of gold. Many were talented performers, singers, and musicians, whose artistry provided much-needed cultural respite.

Further down the social ladder, but no less integral to the Klondike economy, were the prostitutes. These women operated in a range of settings, from the relatively upscale "parlor houses" where madams oversaw a coterie of girls, to the more common "cribs" – small, single rooms rented by individual women along the infamous Paradise Alley. Life in these establishments was harsh. While the potential for earning was high – a single night’s company could command anywhere from $20 to $1,000 in gold dust, depending on the client and the woman’s reputation – the risks were enormous. Disease, violence, and exploitation were constant threats. Yet, for many, it offered a chance at independence, a means to escape a past, or to build a future that conventional society denied them.

One of the most legendary figures among the Klondike’s entertainers was Kathleen Eloise Rockwell, better known as Klondike Kate. A vivacious, red-haired performer from Kansas, Kate arrived in Dawson in 1898 and quickly became the "Queen of the Yukon." Her powerful singing voice, mesmerizing stage presence, and ability to hold a crowd captivated made her an instant sensation. She was renowned for her "Flame Dance," a theatrical performance with a red scarf that reputedly drove men wild. Klondike Kate wasn’t just a performer; she was a shrewd businesswoman. She invested her substantial earnings in mining claims and real estate, demonstrating an entrepreneurial spirit that mirrored many of the men she entertained. While her personal life was often tumultuous, her public persona was one of strength and glamour, embodying the audacious spirit of the Klondike itself. She famously once declared, "I never loved a man enough to marry him," reflecting a defiant independence that many women of her era could only dream of.

Then there were the madams, the ultimate entrepreneurs of the "shady" world. Figures like Nellie "The Pig" May carved out their own empires. Nellie, a woman of substantial girth and even more substantial business acumen, ran one of Dawson’s most popular sporting houses. She was known for her strict but fair management, providing her girls with clean accommodations, good food, and a measure of protection, in exchange for a significant cut of their earnings. Nellie understood the market and offered a slice of domesticity and comfort that the lonely prospectors desperately craved. Her establishments were often more than just brothels; they were social hubs where men could find a hot meal, a warm bed, and a listening ear, making them feel less isolated in the vast wilderness.

It’s crucial to acknowledge the complex motivations and experiences of these women. While some were undoubtedly exploited, many exercised remarkable agency. They were often shrewd entrepreneurs, managing their finances, investing in local businesses, and even accumulating significant wealth. They understood supply and demand better than most, recognizing that in a town dominated by men hungry for female companionship, their services were invaluable. Some used their earnings to leave the life behind, establishing legitimate businesses or returning home with a newfound fortune.

However, the "shady ladies" also faced immense social stigma. While tolerated, and even celebrated for their entertainment value, they were largely excluded from "respectable" society. The wives of merchants, government officials, and successful mine owners formed their own social circles, maintaining a careful distance from those who operated in the twilight world of dance halls and cribs. Yet, this societal hypocrisy was often palpable; the same men who frequented the "sporting houses" would shun these women in broad daylight. This created a paradoxical existence where these women were economically powerful but socially marginalized.

The "shady ladies" contributed to the Klondike in ways that went beyond mere commerce. They were the social glue, the purveyors of dreams, and the providers of comfort in a harsh, unforgiving land. They brought color, music, and a touch of glamour to a world otherwise dominated by mud, canvas, and the monotonous grind of gold mining. Their presence, however controversial, was integral to the town’s character and its development. They often became pillars of their communities, contributing to charities, supporting local businesses, and even, in some cases, raising families.

As the gold rush waned and the easy pickings diminished, so too did the fortunes of many "shady ladies." Some moved on to other boomtowns, following the next big strike. Others retired, some wealthy, some impoverished. The Klondike, like all frontiers, eventually settled into a more conventional existence, and with it, the wild, uninhibited spirit that had allowed these women to thrive began to fade.

Today, the "shady ladies" of the Klondike remain more than mere footnotes in history. They represent a fascinating, often uncomfortable, chapter in the story of the American and Canadian West. They were survivors, entrepreneurs, and entertainers who navigated a challenging world with courage, wit, and often, a fierce independence. Their stories challenge simplistic notions of morality and highlight the complex realities of life on the frontier. They remind us that history is not just about the celebrated heroes, but also about the forgotten, the marginalized, and those who dared to live life on their own terms, even if those terms were dictated by the harsh demands of a gold-crazed world. Their legacy, etched in the permafrost and whispered through the winds of time, reminds us of the untamed soul of the Klondike, and the resilient, often audacious, women who helped define it.