The Ghost Road: Tracing the Enduring Spirit of the Great Indian Warpath

Beneath the roar of Interstate 81 or the quiet hum of US Route 11, under the asphalt and the concrete, lies a ghost. It is a spirit of passage, etched into the very topography of North America for millennia. This spectral presence is the Great Indian Warpath, a network of ancient trails that once served as the pulsing arteries of Indigenous life across the vast eastern woodlands. Far more than just routes for conflict, these paths were the superhighways of their time, facilitating trade, diplomacy, hunting, and the movement of entire nations. Today, its echoes resonate in the modern infrastructure that often directly overlays its ancient routes, a powerful, if often unseen, testament to a deep and complex history.

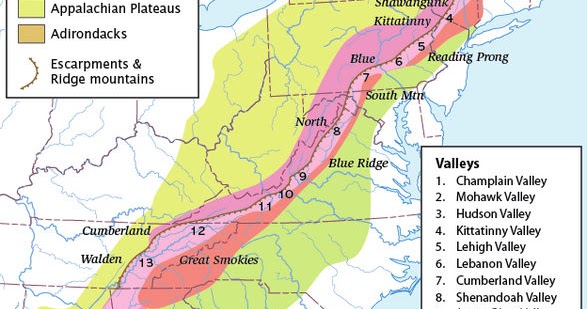

The Great Indian Warpath wasn’t a singular, well-defined thoroughfare like the Oregon Trail. Instead, it was a sprawling, interconnected system of trails, often no more than a foot or two wide, worn smooth by countless generations of moccasined feet. Its main artery, often referred to as the "Great Warrior’s Path," stretched from the Mohawk Valley in what is now New York, snaking south through the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, across the Appalachian Mountains, and into the heartlands of the Cherokee, Creek, and Choctaw nations in present-day Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee. Branching off from this central spine were countless subsidiary paths, forming a vast web that connected disparate tribal communities, stretching west towards the Ohio River Valley and east to the Atlantic coast.

Long before European boots trod upon this continent, these paths were vibrant corridors of commerce and cultural exchange. Indigenous nations, often perceived by early Europeans as isolated and primitive, maintained sophisticated trade networks that spanned thousands of miles. Along the Warpath, tribes exchanged goods essential for survival and status: mica from the southern Appalachians, prized for its decorative and ceremonial qualities; flint for tools and weapons from Ohio; salt from various licks; seashells from the coast, valued for adornment and currency; and furs and pelts from the northern forests. These exchanges fostered not just economic ties but also diplomatic relations, forming alliances and sometimes leading to conflicts over resources and territory.

For the Cherokee, who inhabited much of the southern portion of the main Warpath, it was a vital lifeline. They knew it by names like "Tali Tsisgwayahi" (the Great Trading Path) or simply "Long Path." It connected their scattered towns, from the mountainous Overhill towns to the Lower Towns and Valley Towns, facilitating internal communication and their extensive trade with the Creek, Shawnee, and Iroquois. The very act of walking these paths was imbued with spiritual significance, a journey across ancestral lands, imbued with the spirits of those who had walked before.

When European colonists first cast their gaze upon these lands, they quickly recognized the strategic importance of these pre-existing Indigenous routes. Traders, often Scots-Irish and German immigrants, were among the first Europeans to extensively use the Warpath, following Indigenous guides deep into the interior to barter for deerskins and furs. These early encounters were often characterized by a complex mix of cooperation and exploitation, laying the groundwork for future conflicts.

The 18th century saw the Warpath transform from a primarily Indigenous thoroughfare to a contested frontier. During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), sections of the Warpath became crucial military routes for both British and French forces, as well as their Indigenous allies. General Edward Braddock’s ill-fated expedition in 1755, though a disaster for the British, saw his forces attempt to widen a segment of an Indigenous trail into a military road, illustrating the European imperative to adapt and dominate these existing networks.

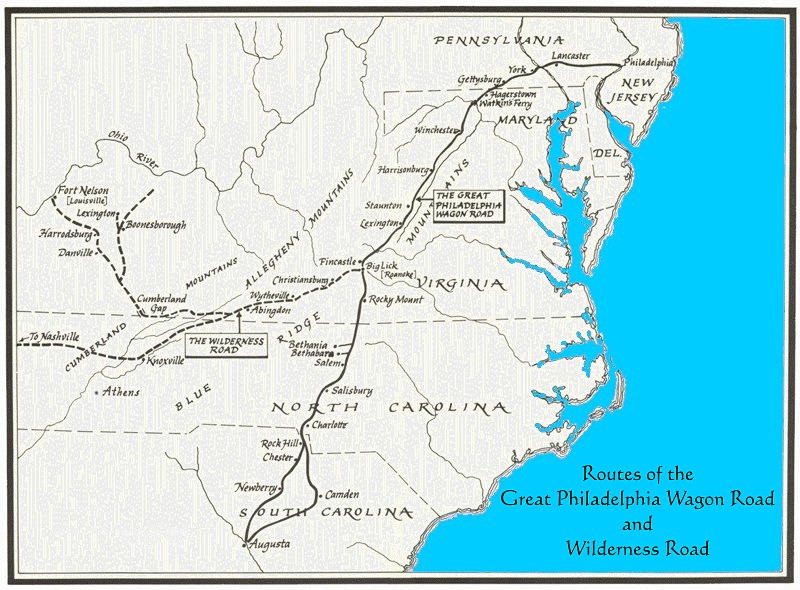

Later, during the American Revolution, the Warpath was again a stage for conflict, with Native American tribes often caught between the warring colonial powers and the British Crown. The subsequent westward expansion of the newly formed United States saw pioneers and frontiersmen, like the legendary Daniel Boone, utilize and further modify sections of the Warpath. Boone’s famous Wilderness Road, which opened up Kentucky to white settlement, largely followed a portion of the Great Indian Warpath, forever altering the landscape and the fate of the Indigenous peoples whose lands it traversed. "I have never been lost," Boone famously said, "but I was bewildered once for three days." One can only imagine the wisdom gleaned from the intricate knowledge of Indigenous trails that guided him.

The very name "Warpath" conjures images of conflict, and indeed, it was a route for raiding parties and military expeditions. Inter-tribal warfare was a reality long before Europeans arrived, often driven by competition for hunting grounds, resources, or vengeance. The Iroquois, a powerful confederacy from the north, frequently used sections of the Warpath to launch raids against southern tribes like the Cherokee and Shawnee, creating a constant state of vigilance along the routes. However, to focus solely on the "war" aspect is to miss the broader picture. The path was also a conduit for peace negotiations, for the safe passage of ambassadors, and for the cultural diffusion that enriched diverse Indigenous societies. It was a crucible where identities were forged and histories intertwined.

Yet, the Warpath’s legacy is also stained by profound tragedy. As American settlers pushed relentlessly westward, the Warpath became a route of dispossession. The relentless pressure for land led to a series of treaties, often coerced and violated, that chipped away at Indigenous territories. The ultimate, most devastating chapter in this story is the forced removal of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations during the 1830s – a period infamously known as the Trail of Tears. While not a single, continuous path, various segments of the Great Indian Warpath and its branches were utilized as forced migration routes, transforming a path of ancestral memory into a corridor of unimaginable suffering, sickness, and death. Thousands perished as they were driven from their homelands, their forced march a stark and cruel irony to the ancient paths their ancestors had walked freely for millennia.

Today, the physical remnants of the Great Indian Warpath are often subtle, sometimes requiring a trained eye to discern. Yet, its presence is undeniable. Major modern highways, such as US-11 and I-81 in the Shenandoah Valley, follow the exact contours of the ancient Warpath for hundreds of miles. In Tennessee, segments of US-19 and US-23 trace its path through the mountains. Even local roads and county lines sometimes reflect the twists and turns of these ancient routes, a testament to the enduring logic of their original layout. The Appalachian Trail, a modern marvel for hikers, occasionally intersects or parallels these historical routes, offering a glimpse into the arduous journeys undertaken by its earlier travelers.

For Indigenous peoples, the Warpath is more than a historical curiosity; it is a living connection to their past, a sacred landscape imbued with memory and resilience. Efforts are ongoing to recognize and preserve these ancient pathways, not just as archaeological sites, but as vital cultural resources. Historical markers occasionally dot the landscape, offering fleeting acknowledgements, but the true story of the Warpath requires a deeper engagement – an understanding that beneath the convenience of modern travel lies a narrative of profound human endeavor, sophisticated societies, and immense hardship.

The Great Indian Warpath remains a potent, if often unseen, testament to the ingenuity and endurance of North America’s first peoples. It challenges the simplistic narratives of "discovery" and "wilderness," revealing instead a continent crisscrossed by intricate human networks, vibrant cultures, and complex histories. As we drive along our modern highways, let us remember the ghost road beneath, the generations of footsteps that shaped it, and the stories—both triumphant and tragic—that it continues to whisper from the deep past. It reminds us that history is not buried, but merely paved over, waiting for us to peel back the layers and truly see.