The Great Shamokin Path: An Ancient Artery of Power, Trade, and Transformation in Colonial Pennsylvania

Before paved roads and rail lines crisscrossed the rugged terrain of Pennsylvania, an intricate network of ancient pathways served as the lifeblood of indigenous communities. These routes, forged by countless moccasin-clad feet over millennia, were not merely trails but arteries of communication, trade, and cultural exchange. Among them, none was perhaps more vital or witnessed more profound transformations than the Great Shamokin Path. Stretching approximately 120 miles from the Susquehanna River to the Allegheny River, this ancient thoroughfare connected the heart of Native American Pennsylvania with the burgeoning European frontier, becoming a stage for diplomacy, commerce, and ultimately, conflict that reshaped the destiny of a continent.

A Lifeline Forged by Time and Necessity

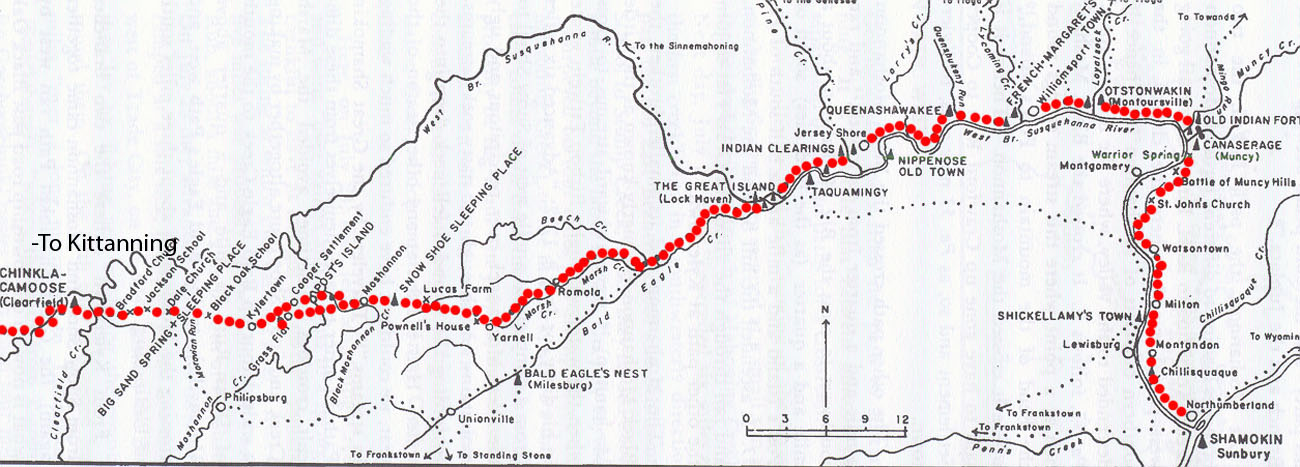

The Great Shamokin Path’s origins are shrouded in the mists of prehistory. It was an indigenous creation, developed and maintained by generations of Lenape (Delaware), Shawnee, Susquehannock, and later, Seneca peoples. Its eastern terminus lay at Shamokin, modern-day Sunbury, a significant multi-tribal village and political center at the confluence of the West Branch and North Branch of the Susquehanna River. From there, it wound westward, largely following the valleys of the Mahanoy and Mahoning Creeks, eventually reaching the Allegheny River near Kittanning, a prominent Native American town and trading post.

More than a mere track through the wilderness, the Great Shamokin Path was a testament to indigenous ingenuity and understanding of the landscape. It was designed to be efficient, avoiding the steepest climbs where possible, finding natural crossings at rivers and streams, and often following game trails that offered the most direct routes. For centuries, it facilitated inter-tribal relations, allowing for the exchange of goods like furs, tools, pottery, and foodstuffs. It was a route for diplomatic envoys, for warriors on punitive expeditions, and for families migrating with the seasons or in search of new hunting grounds. The path was a living entity, echoing with the whispers of forgotten tongues and the rustle of countless journeys.

"These paths were the internet of their time," observes historian Dr. William A. Hunter, referring to the indigenous trail networks. "They connected people, ideas, and goods over vast distances, far more effectively than early European attempts at road-building." The Great Shamokin Path, in particular, was strategically significant, linking the eastern agricultural lands and trading posts to the vast hunting grounds and resource-rich territories of the Ohio Country.

The Arrival of Europeans: A New Dynamic

The arrival of European colonists introduced a new dynamic to this ancient system. As early as the late 17th and early 18th centuries, adventurous fur traders, often of Scottish-Irish or German descent, began to venture beyond the settled areas of eastern Pennsylvania. They quickly recognized the utility and efficiency of the Native American paths. The Great Shamokin Path, with its direct route to the west, became an indispensable conduit for their trade with indigenous communities.

These traders, such as James Le Tort, John Fraser, and later, the renowned Conrad Weiser, traveled the path laden with blankets, tools, firearms, and rum, exchanging them for beaver, deer, and bear pelts. Their presence, while initially beneficial to both sides, irrevocably altered the path’s character. What was once solely an indigenous artery now became a corridor of cultural collision. European goods, particularly firearms and alcohol, disrupted traditional economies and social structures, while the insatiable demand for furs led to overhunting and territorial disputes.

The town of Shamokin itself, already a vital hub, grew in importance as a meeting point between the two cultures. It became a crucible where Native American leaders, colonial officials, and traders negotiated, celebrated, and often, struggled to understand one another. Conrad Weiser, the famous Pennsylvania diplomat and interpreter, made numerous journeys along segments of the path, mediating between the colonial government and various Native American nations, particularly the powerful Iroquois Confederacy who exerted significant influence over the Lenape and Shawnee in Pennsylvania. His journals offer glimpses into the arduous nature of these journeys and the complex political landscape of the time.

A Path to Conflict and Conquest

As the 18th century progressed, the Great Shamokin Path transitioned from a route of commerce to one of strategic military importance. The escalating rivalry between the British and French for control of North America, culminating in the French and Indian War (1754-1763), saw the path become a critical military artery. Both sides understood that control of the interior—and the routes that led there—was paramount.

Native American warriors, often allied with the French, used the path for raids on the Pennsylvania frontier, striking fear into the hearts of settlers. Conversely, for British military strategists, it offered a direct, albeit perilous, route to the heart of the Ohio Country, a region fiercely contested by France and its indigenous allies. While General Forbes ultimately forged his own road further south to capture Fort Duquesne (modern-day Pittsburgh), the intelligence and logistical understanding gained from previous explorations along routes like the Great Shamokin Path were invaluable.

The end of the French and Indian War did not bring peace. Pontiac’s War (1763-1766), an indigenous uprising against British expansion, saw the Great Shamokin Path once again become a battleground. Native American forces, enraged by British policies and continued encroachment on their lands, used the path to launch attacks on colonial settlements and forts. Fort Augusta, built at Shamokin by the British in 1756, became a vital defensive outpost, guarding the eastern terminus of the path and the strategic Susquehanna.

Treaties, Land Cessions, and the Path’s Transformation

The path’s fate was irrevocably altered by treaties that followed these conflicts. The most significant of these was the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768. Negotiated between the British and the Iroquois Confederacy, this treaty saw the Iroquois cede vast tracts of land in Pennsylvania to the colonial government, including much of the territory through which the Great Shamokin Path ran. While the Iroquois claimed dominion over these lands, the Lenape and Shawnee who actually lived there felt betrayed and disenfranchised.

The Fort Stanwix Treaty effectively opened up much of central and western Pennsylvania for European settlement, particularly the lands east of the Allegheny River. The Great Shamokin Path, in a cruel twist of irony, became a de facto boundary marker for lands soon to be lost and a primary route for the very settlers who would displace its original creators.

As the frontier pushed westward, the faint tracery of the Great Shamokin Path did not vanish. Instead, it evolved. Packhorse trails broadened into wagon roads. Taverns and small settlements sprang up along its course. What was once an indigenous footpath became a crucial part of the emerging colonial infrastructure. Portions of modern Route 422, stretching from Sunbury to Kittanning, and other local roads, subtly echo the ancient alignment of the path, a testament to the enduring logic of its original design.

Echoes in the Modern Landscape

Today, fragments of the Great Shamokin Path persist, not just in the paved roads that overlie its course, but in the landscape itself. Hiking trails in state parks and forests, such as those in the Susquehanna and Allegheny watersheds, occasionally follow stretches of the original path. Historical markers, often small and easily overlooked, sometimes denote its general route or significant points along it. The very names of towns and creeks – Mahoning, Shamokin, Kittanning – echo its forgotten story.

For modern Pennsylvanians, the Great Shamokin Path serves as a powerful reminder of the complex and often painful history that shaped the state. It embodies the ingenuity and resilience of Native American peoples, their deep connection to the land, and their profound impact on the development of the region. It also stands as a stark reminder of the forces of colonialism, the clash of cultures, and the irreversible changes wrought by westward expansion.

"To understand Pennsylvania," writes historian Paul A.W. Wallace, "one must understand its paths." The Great Shamokin Path is more than a historical footnote; it is a profound narrative etched into the very soil of the commonwealth. It is a story of connection, exchange, adaptation, and loss. To walk its ghost today, even metaphorically through maps and historical accounts, is to touch the past – to hear the faint echoes of moccasins on soft earth, the creak of trader’s packs, the urgent commands of warriors, and the quiet dignity of a people who once called this land home, guided by a path that bound their world together. Its legacy is a call to remember, to honor, and to understand the deep, interwoven tapestry of Pennsylvania’s past.