Echoes and Enduring Voices: The Resilient Journey of Virginia’s Native Americans

RICHMOND, Virginia – From the ancient whispers carried on the winds sweeping across the Blue Ridge Mountains to the rhythmic pulse of modern powwows along the tidewater rivers, the story of Virginia’s Native Americans is one of profound endurance, unyielding cultural preservation, and a triumphant resurgence against centuries of adversity. Far from being relegated to history books, these indigenous peoples, with roots stretching back over 15,000 years, are a vibrant, integral part of the Commonwealth’s identity, actively shaping its present and future.

Their narrative is complex, rich with sophisticated societies that thrived long before the arrival of European settlers, marked by devastating conflicts and systemic oppression, and illuminated by a steadfast refusal to be erased. Today, Virginia is home to 11 state-recognized tribes, seven of which have also achieved federal recognition, a testament to their unwavering spirit and relentless advocacy.

A Land of Nations: Before European Contact

Before the Jamestown colonists dropped anchor in 1607, the land now known as Virginia was a tapestry of diverse indigenous nations. The most dominant power in the eastern part of the state was the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom, a sophisticated political and economic alliance of some 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes, numbering an estimated 15,000 people at its peak. Led by the formidable Chief Wahunsenacawh, famously known as Chief Powhatan, this confederacy controlled vast territories, meticulously managing natural resources, cultivating crops like corn, beans, and squash, and engaging in extensive trade networks.

Further west, in the Piedmont and mountainous regions, lived the Monacan Nation, an Iroquoian-speaking people with distinct cultural practices, known for their elaborate burial mounds and deep connection to the land’s spiritual essence. Other significant tribes included the Nottoway and Meherrin, Iroquoian speakers in the southeastern part of the state, and numerous smaller independent groups.

These societies were not primitive; they were complex civilizations with intricate social structures, advanced agricultural techniques, sophisticated governance, and rich oral traditions that passed down generations of knowledge, ethics, and spirituality. Their relationship with the land was one of stewardship, not ownership, understanding that their survival was intrinsically linked to the health of the environment.

First Contact and the Dawn of Conflict

The arrival of the English at Jamestown marked an irreversible turning point. Initially, interactions between the Powhatan and the English were a mix of wary trade and escalating tension. Chief Powhatan, a shrewd leader, quickly grasped the potential threat the newcomers posed. He famously expressed his skepticism to Captain John Smith, as recorded by Smith himself: "Why should you take by force that which you may have by love? Why should you destroy us who have provided you with food? What can you get by war?"

This poignant question foreshadowed centuries of conflict. While the legend of Pocahontas, Chief Powhatan’s daughter, and her supposed role in saving Smith’s life is widely romanticized, her story is far more complex, representing a tragic bridge between two clashing worlds. Her capture, conversion to Christianity, and marriage to John Rolfe did bring a temporary peace, but it was fragile.

The subsequent decades were marked by cycles of warfare, land encroachment, and devastating disease outbreaks. Native populations, lacking immunity to European diseases like smallpox and measles, were decimated. The Great Massacre of 1622, orchestrated by Chief Opechancanough, Powhatan’s successor, was a desperate attempt to drive out the English. While initially successful in inflicting heavy casualties, it ultimately led to intensified English retaliation and further erosion of Native power and territory. By the mid-17th century, the Powhatan Confederacy was largely shattered, its people pushed onto ever-shrinking reservations.

The Long Night: Erasure and Resilience

The colonial period and the subsequent centuries were a dark chapter for Virginia’s Native Americans. Treaties were broken, land was stolen, and their cultures were systematically suppressed. Many were forced to assimilate, intermarry, or move westward, leading to a period often referred to as "hidden" or "underground" survival.

However, the most insidious challenge came in the 20th century with the passage of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. This eugenics-inspired law, championed by Registrar of Vital Statistics Walter Plecker, legally classified all Virginians as either "white" or "colored," with "colored" encompassing Black individuals and anyone with even a trace of non-white ancestry. The Act deliberately sought to erase Native American identity by reclassifying them as "colored" or "Negro" on birth certificates, marriage licenses, and other official documents.

"Plecker’s campaign was a paper genocide," explains Dr. Helen Rountree, a renowned historian of Virginia Indians. "He believed that anyone with a hint of non-white blood was simply ‘colored,’ and he actively manipulated records to force this classification on Native families. This act made it incredibly difficult for tribes to prove their continuous existence and heritage, impacting their ability to gain state and later federal recognition."

Despite this legal and social assault, Virginia’s Native communities refused to vanish. They maintained their cultural practices in secret, passed down oral histories, preserved traditional crafts, and continued to live as distinct communities, often in isolated rural areas where they could maintain a degree of autonomy. Churches often became centers for cultural preservation, and family gatherings served as vital links to their heritage.

The Fight for Recognition and Revival

The latter half of the 20th century saw a powerful resurgence of Native American advocacy across the United States, and Virginia was no exception. Tribes began to openly assert their identities, challenging the historical injustices and demanding recognition.

A pivotal moment came in 1989 with the creation of the Virginia Council on Indians, a state body dedicated to advising the Governor and General Assembly on issues affecting Native communities. This was a significant step towards formal state acknowledgment. Over the next few decades, the Commonwealth officially recognized 11 tribes: the Pamunkey, Mattaponi, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond, Monacan, Nottoway, Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), and Patawomeck.

While state recognition provided some benefits and official acknowledgment, the ultimate goal for many was federal recognition. Federal recognition grants tribes sovereign status, allowing them to govern themselves, access federal funding for healthcare, education, and housing, and protect their cultural resources. The process is notoriously arduous, requiring extensive historical and genealogical proof of continuous tribal existence from first contact to the present. Plecker’s "paper genocide" had made this particularly challenging for Virginia tribes.

After decades of tireless lobbying, historical research, and legal battles, a monumental victory arrived. In 2015, the Pamunkey Indian Tribe became the first federally recognized tribe in Virginia. Then, in January 2018, Congress passed the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act, granting federal recognition to six additional tribes: the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond, and Monacan Indian Nation.

"This is not just a piece of paper; it’s an affirmation of who we are, who we’ve always been," said Chief Stephen R. Adkins of the Chickahominy Indian Tribe at the time of the bill’s signing. "It allows us to continue our work for our people with the resources and respect that come with sovereign nation status."

Contemporary Challenges and Triumphs

Today, Virginia’s federally and state-recognized tribes are vibrant, dynamic communities actively engaged in cultural revitalization, economic development, and environmental stewardship.

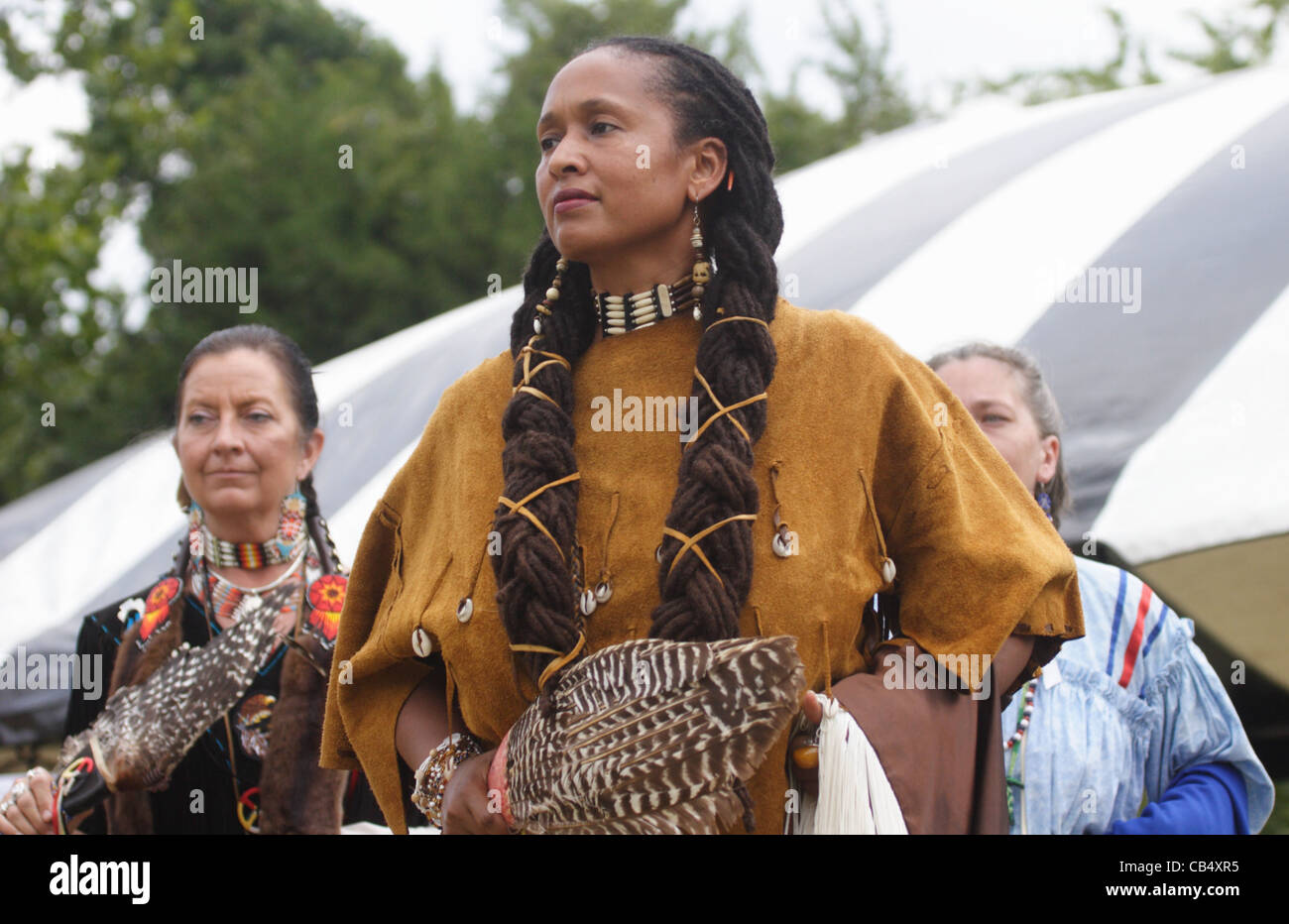

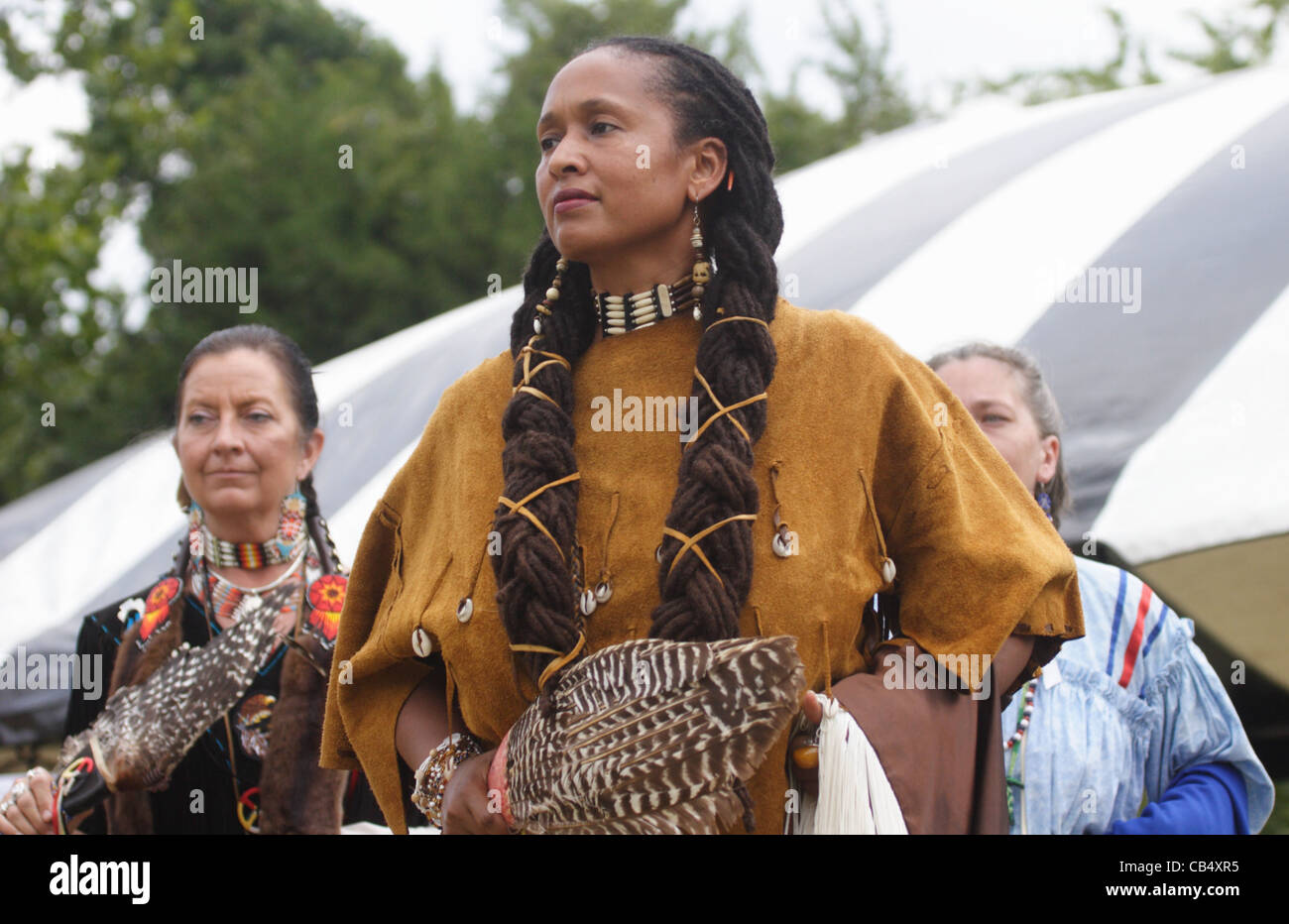

Cultural Preservation: There is a strong emphasis on reclaiming and celebrating their heritage. Tribes host annual powwows, open to the public, that showcase traditional dances, drumming, storytelling, and crafts. Language revitalization programs are underway, particularly for Algonquian and Siouan languages, ensuring that the ancient tongues are not lost. The Pamunkey Indian Museum and Cultural Center, for instance, provides a window into their rich history and living traditions.

Economic Development: Federal recognition has opened doors for economic self-sufficiency. Tribes are exploring various ventures, from gaming operations (Pamunkey Indian Tribe is developing a casino in Norfolk) to eco-tourism and aquaculture. The Pamunkey, for example, have a long history of oyster harvesting and are leaders in sustainable aquaculture, a practice deeply rooted in their traditional connection to the Chesapeake Bay.

Environmental Stewardship: Many tribes are at the forefront of environmental conservation efforts, drawing on their ancestral knowledge of the land and water. They advocate for clean water, healthy forests, and sustainable resource management, often collaborating with state and federal agencies to protect sacred sites and natural habitats.

Education and Advocacy: Tribes are actively working to correct historical narratives in schools and public discourse, ensuring that their accurate and comprehensive story is told. They advocate for policies that address issues such as healthcare disparities, educational opportunities, and the protection of burial grounds and sacred sites.

Despite these triumphs, challenges remain. Stereotypes persist, land claims are ongoing, and the fight for full equity and understanding continues. The Patawomeck, Nottoway, and Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) tribes continue their pursuit of federal recognition, facing the same rigorous requirements their sister tribes overcame.

A Future Rooted in the Past

The journey of Virginia’s Native Americans is a powerful testament to the strength of identity and the resilience of the human spirit. From the sophisticated societies that thrived millennia ago to the tenacious fight for survival against overwhelming odds, and now to a vibrant era of cultural resurgence and self-determination, their story is one of an enduring presence.

As Chief G. Anne Richardson of the Rappahannock Tribe eloquently stated, "We are still here. Our ancestors paved the way for us to be here. And we will continue to walk in their footsteps, ensuring that our children and grandchildren know who they are and where they come from."

Their voices, once silenced or distorted, now echo with renewed strength, reminding all Virginians that the history of this Commonwealth is incomplete without the acknowledgment, respect, and celebration of its original peoples, who continue to enrich the land they have called home for countless generations.