Threads of Resilience: The Enduring Art of Salish Weaving

In the verdant landscapes of the Pacific Northwest, where ancient forests meet the restless sea, a profound artistry has woven itself into the very fabric of Indigenous life for millennia. This is the realm of Salish weaving, a sophisticated and deeply spiritual practice that, despite facing near-extinction, is now experiencing a vibrant resurgence. Far more than mere craft, Salish weaving is a living testament to cultural continuity, a language spoken through fiber, pattern, and the patient hands of its practitioners.

For thousands of years, the Coast Salish peoples – including the Squamish, Sto:lo, Musqueam, Snuneymuxw, Cowichan, and many others across what is now British Columbia and Washington State – were renowned for their exquisite textiles. These were not just functional items; they were symbols of wealth, status, and spiritual connection, integral to ceremonies, trade, and daily life. The blankets, cloaks, and regalia produced were of such high quality that early European explorers and traders marveled at their intricacy and beauty.

The arrival of European settlers, however, brought devastating changes. Disease, colonial policies, and the forced assimilation of Indigenous peoples through residential schools severely disrupted traditional life, including the transmission of weaving knowledge. Materials became scarce, and the practice itself was suppressed. By the mid-20th century, the intricate techniques and patterns of Salish weaving were on the brink of being lost forever, held onto by only a handful of dedicated elders.

The Sacred Materials: Wool, Dog Hair, and Plant Fibers

The heart of traditional Salish weaving lies in its unique materials, each imbued with cultural and spiritual significance. The most prized fiber was the wool of the mountain goat (Oreamnos americanus), a challenging animal to hunt in its perilous alpine habitat. This wool, known for its warmth and durability, was not merely a resource; it was considered sacred, often associated with spiritual power and purity. Weavers would painstakingly gather shed wool from the mountains or obtain it through trade, a testament to the effort and respect involved in its acquisition.

Equally unique to Coast Salish weaving was the use of Salish Wool Dog hair. These small, white, long-haired dogs were specially bred for their woolly coats, much like sheep. Historical accounts describe villages keeping large packs of these dogs, their hair shorn, mixed with mountain goat wool, and then spun into yarn. Tragically, with the advent of European wool and blankets, and the disruption of traditional lifestyles, the Salish Wool Dog breed became extinct in the early 20th century, a poignant loss reflecting the broader impact of colonization.

Beyond animal fibers, Salish weavers also incorporated a variety of plant materials. Inner cedar bark, known for its strength and natural resistance to decay, was meticulously prepared—shredded, softened, and often twisted with other fibers. Nettle (genus Urtica) was another common plant fiber, processed to yield strong, fine threads. These plant materials provided different textures and properties, allowing for a diverse range of woven goods, from sturdy mats and baskets to lighter garments.

Preparing these raw materials was an art in itself. Fibers were cleaned, degreased, and often mixed with a white earth called "kaolin" or "pipe clay" to enhance their natural brightness and act as a mordant for dyes. Natural dyes, derived from plants like Oregon grape (yellow), alder bark (reddish-brown), and various berries (blues, purples), were used sparingly but effectively to create subtle color variations. The yarn was then spun using simple yet effective tools: spindles with carved wooden whorls, often depicting ancestral or animal figures, imbuing the tools themselves with spiritual power.

Tools and Techniques: A Tapestry of Ingenuity

The looms used by Salish weavers were elegantly simple, yet allowed for remarkable complexity in the finished textiles. The most common was the upright loom, consisting of two vertical posts and two horizontal bars. The warp threads (the stationary threads that run lengthwise) were strung between the horizontal bars, and the weaver would manipulate the weft threads (the threads woven across the warp) using her fingers, bone needles, or small wooden beaters.

Unlike many other weaving traditions that use a shuttle, Salish weavers primarily employed a finger-weaving technique, allowing for incredible control over each individual thread. This direct interaction with the fibers contributes to the unique texture and appearance of Salish textiles.

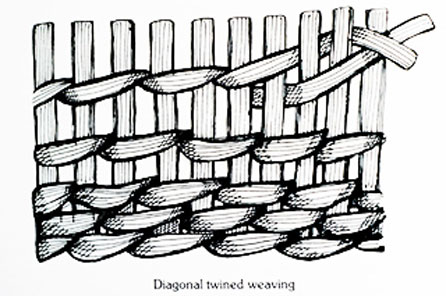

Several key weaving techniques characterized Salish work:

-

Plain Twill Weave: This is a fundamental technique where the weft thread passes over one or more warp threads and then under two or more warp threads, creating a diagonal pattern. It’s known for its durability and flexibility. Many Coast Salish blankets feature distinct twill patterns, often forming geometric designs.

-

Wrapped Twining: In this technique, the weft threads are twined around the warp threads, often wrapping around two warps at a time. This creates a dense, strong fabric. It’s particularly effective for creating patterns where one color appears to "float" over another.

-

Pile Weaving: This highly specialized technique, often seen in ceremonial blankets, involves introducing extra weft threads that are looped and then cut, creating a soft, plush surface, similar to a modern carpet. These pile blankets were extremely luxurious and highly prized, demonstrating the advanced skill of the weavers. They required vast amounts of prepared wool and meticulous execution.

-

Imbrication (often used in basketry but influences weaving patterns): While primarily a basketry technique where decorative bark or grass is wrapped around basket coils, the visual effect of imbrication – creating raised, textured patterns – is often echoed in woven designs through clever manipulation of warp and weft.

Patterns and Symbolism: Stories Woven into Form

Salish weaving patterns are deeply symbolic, often abstract representations of the natural world, spiritual beings, or ancestral narratives. Unlike some other Northwest Coast art forms that feature highly stylized representational figures (like totems), traditional Salish weaving tends towards geometric precision and repetition.

Common patterns include:

- Diamonds: Often representing eyes, or reflecting light and water.

- Triangles: Mountains, human figures, or various natural elements.

- Squares and Rectangles: Land divisions, houses, or stable foundations.

- Zigzags and Chevrons: Movement, water, or lightning.

- "X" shapes: Often symbolizing connection or crossing paths.

While abstract, these geometric forms are imbued with specific meanings, passed down through generations. A diamond pattern might signify a watchful ancestor, while a series of interconnected triangles could represent the peaks and valleys of a journey. The repetition of these patterns creates a rhythmic visual language that speaks of order, balance, and the interconnectedness of all things.

"Every thread, every pattern, tells a story," explains Mary Williams, a contemporary Snuneymuxw weaver. "It’s not just about aesthetics; it’s about our history, our values, our connection to the land and our ancestors. When I weave, I feel their hands guiding mine."

Some patterns also evoke zoomorphic figures, though often in a highly abstract or fragmented way. A series of triangles might subtly suggest a bird’s wings, or a collection of squares could hint at a frog’s powerful legs. These designs are not meant to be literal depictions but rather evocations of the spiritual power and characteristics associated with these creatures.

The Revival: Reclaiming Threads of Identity

The story of Salish weaving is one of remarkable resilience. In the latter half of the 20th century, a few visionary elders, often working in isolation, kept the flame of knowledge alive. They recognized the profound importance of these traditions for cultural identity and began to teach younger generations.

One pivotal figure in the revival was Susan Pavel, a Squaxin Island weaver who, along with others, dedicated herself to meticulously researching historical pieces, studying museum collections, and learning from the few remaining elder weavers. Through their efforts, techniques that had been dormant for decades were painstakingly relearned and documented.

Today, cultural centers, tribal organizations, and universities across the Coast Salish territories are actively supporting the resurgence of weaving. Workshops are held, apprenticeships are fostered, and new generations are embracing the loom. This revival is not merely about preserving an art form; it is a vital act of cultural revitalization, strengthening community bonds, fostering language preservation, and reconnecting Indigenous youth with their heritage.

"We are not just weaving blankets; we are weaving our history back into existence," says Musqueam weaver Debra Sparrow, whose family has been instrumental in the revival. Her work, alongside her sisters and many others, demonstrates the profound impact of intergenerational knowledge transfer. "Each piece carries the prayers, the struggles, and the triumphs of our ancestors. It’s about healing, about reclaiming our voice."

Contemporary Relevance and Future Horizons

The contemporary Salish weaving movement is vibrant and diverse. While deeply rooted in tradition, weavers are also innovating, incorporating new materials (like commercial wools) and adapting traditional patterns in modern contexts. Their work is showcased in galleries, museums, and worn with pride at ceremonies and public events, serving as powerful symbols of Indigenous presence and sovereignty.

However, challenges remain. Sourcing authentic traditional materials, like mountain goat wool, is difficult and often costly. Protecting the intellectual property of traditional designs, ensuring fair compensation for artists, and securing funding for continued teaching and practice are ongoing concerns.

Despite these hurdles, the future of Salish weaving looks bright. A growing number of talented young weavers are committed to carrying on the legacy, ensuring that the intricate knowledge, spiritual connection, and artistic mastery continue to flourish. They are not only preserving an ancient art but also shaping its future, demonstrating that Indigenous cultures are dynamic, adaptable, and eternally resilient.

The threads spun and woven by Salish hands today are not merely fibers; they are lifelines connecting past, present, and future, ensuring that the vibrant heart of Coast Salish culture continues to beat strong, weaving new stories into the enduring tapestry of the Pacific Northwest.