A Century-Long Struggle: The Lumbee Tribe’s Unyielding Quest for Full Federal Recognition

PEMBROKE, NC – For over a century, the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina has navigated a bureaucratic labyrinth, battling for full federal recognition – a status that would acknowledge their inherent sovereignty, unlock vital resources, and rectify a historical injustice. Situated primarily in Robeson County, a vibrant, diverse region in southeastern North Carolina, the Lumbee are the largest state-recognized tribe east of the Mississippi River, boasting a proud and resilient community of over 60,000 members. Yet, despite their deep roots, continuous cultural presence, and a documented history stretching back centuries, they remain in a unique and frustrating limbo: recognized as "Indian" by the U.S. Congress, but explicitly denied the benefits and services afforded to other federally recognized tribes.

This peculiar predicament stems from the Lumbee Act of 1956, a piece of legislation that, on its surface, appeared to grant recognition. However, it contained a crippling caveat, known as the "Proviso," which declared: "Nothing in this Act shall make such Indians eligible for any services performed by the United States for Indians because of their status as Indians." This seemingly innocuous clause has been a millstone around the neck of the Lumbee people for nearly seven decades, effectively rendering their recognition a hollow gesture.

A History Forged in Place

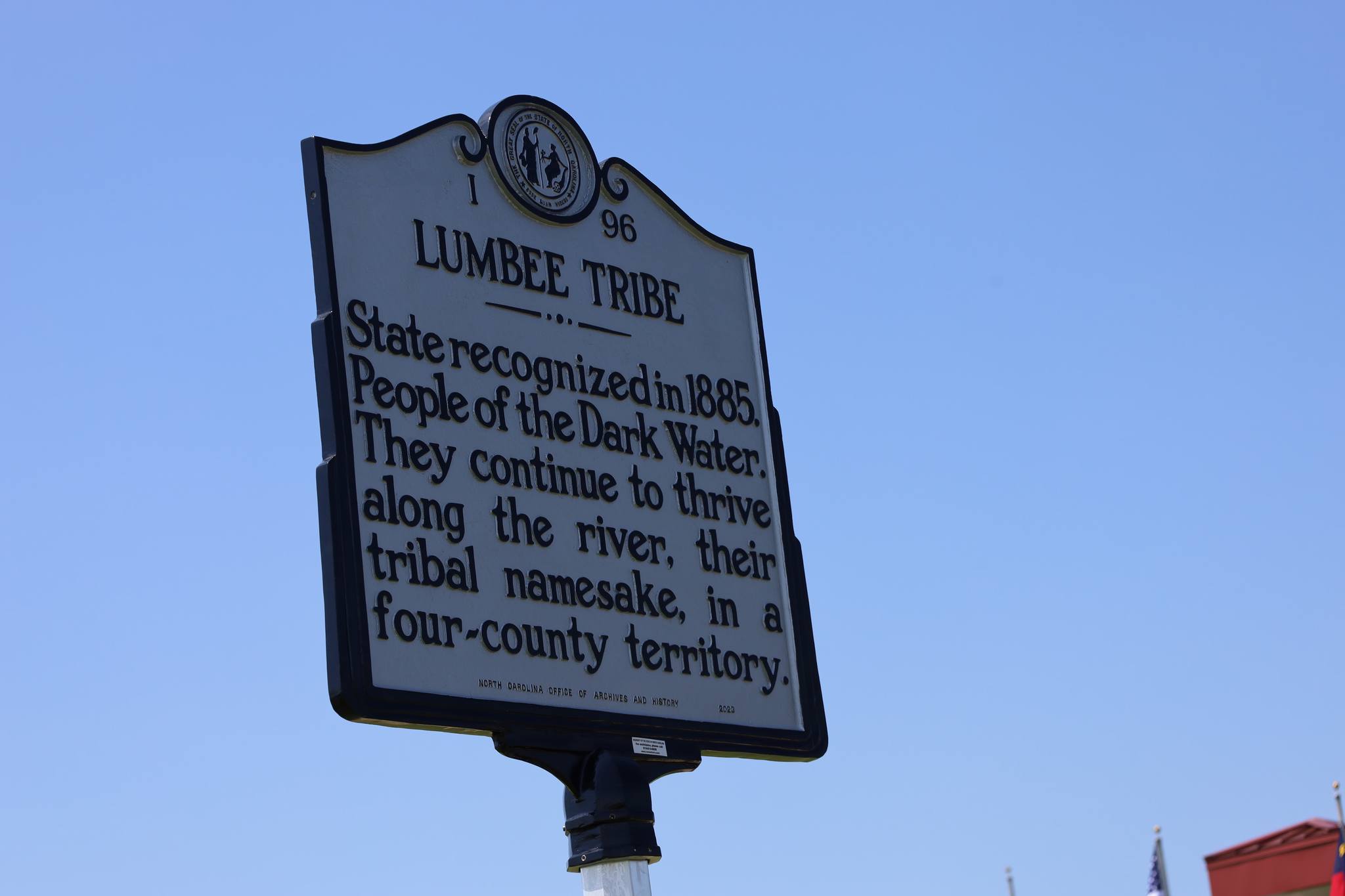

Unlike many Native American tribes who endured forced removal and relocation, the Lumbee have largely remained on their ancestral lands in what is now Robeson County and surrounding areas. Their history is one of continuous presence, adaptation, and fierce self-determination. Descendants of various Siouan, Iroquoian, and Algonquian-speaking peoples, they coalesced as a distinct community in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, maintaining a strong cultural identity despite immense pressures.

Early records refer to them by various names, including the Croatan Indians, a name formally recognized by North Carolina in 1887. By the mid-20th century, the community adopted "Lumbee" – a name derived from the Lumber River, which flows through their traditional territory and is central to their identity and heritage. This evolution of names reflects their adaptive history, not a discontinuity of identity.

The Lumbee’s struggle for federal acknowledgement began in earnest in the late 19th century. They sought the same rights and protections as other Native American tribes, understanding that federal recognition was not merely symbolic but a gateway to self-determination and critical resources. Decades of petitions, lobbying, and congressional bills followed, each met with bureaucratic inertia or partial, insufficient measures.

The 1956 Act was a culmination of these efforts, but its "Proviso" was a devastating blow. "It was a cruel joke," says James Jones, a Lumbee elder and historian. "Congress said, ‘Yes, you are Indian,’ but then immediately said, ‘But you can’t have anything that comes with being Indian.’ It created a second-class status that has haunted us for generations."

The Price of Partial Recognition

The impact of this partial recognition is profound and far-reaching, touching every aspect of Lumbee life. Federally recognized tribes are eligible for funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the Indian Health Service (IHS), which provide essential services in areas like healthcare, education, housing, infrastructure, and economic development. For the Lumbee, these critical lifelines are absent.

"We have to compete for state and local grants like any other community, often against much larger, better-funded entities," explains Chairman John Lowery of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. "Meanwhile, our tribal infrastructure, our healthcare system, our educational programs – they operate on a shoestring budget, relying heavily on the ingenuity and sacrifice of our people."

Healthcare disparities are particularly acute. While federally recognized tribes benefit from IHS clinics and programs, the Lumbee must rely on a patchwork of state and local services, often in a rural area already facing healthcare access challenges. This translates to higher rates of chronic diseases, limited access to specialized care, and a shorter life expectancy.

In education, Lumbee students do not have access to federal programs designed to support Native American students, such as tribal colleges or specific scholarships. Housing initiatives and economic development opportunities, often facilitated by federal grants for recognized tribes, are also largely out of reach, contributing to economic challenges in Robeson County, which remains one of the poorest counties in North Carolina.

Beyond the tangible economic and social impacts, the lack of full recognition is a constant affront to their sovereignty and dignity. "It’s about being seen, truly seen, by your own government," says Dr. Malinda Maynor Lowery, a Lumbee historian and filmmaker. "It’s about having the right to self-govern, to protect your lands, your culture, your children, with the full backing of the federal government, just like every other tribe."

The Path Forward: Legislative Action

For decades, the Lumbee have pursued various avenues for full recognition. The administrative path through the BIA’s Federal Acknowledgment Process is notoriously complex, costly, and time-consuming, requiring tribes to meet seven stringent criteria, including continuous political authority and community identification. While the Lumbee argue they meet these criteria, their unique history – never being removed to a reservation, always maintaining a community structure that might not fit the BIA’s narrow, historically reservation-centric definition of "continuous government" – has made the administrative route problematic.

Therefore, the tribe has consistently sought a legislative solution: an act of Congress to amend the 1956 Lumbee Act and grant full recognition. This legislative path is seen as the most direct and equitable way to rectify a wrong that Congress itself created.

Momentum for such legislation has been building in recent years. The Lumbee Recognition Act (H.R. 65 in the House and S. 136 in the Senate in the current legislative session) enjoys significant bipartisan support. This reflects a growing understanding in Washington, D.C., of the Lumbee’s unique historical circumstances and the inherent unfairness of the 1956 Proviso.

Advocates for the bill highlight that the Lumbee are not seeking a new recognition but rather the completion of an existing, albeit flawed, one. "This isn’t about creating a new tribe or opening a floodgate," explains a congressional aide familiar with the legislation. "This is about fulfilling a promise made in 1956 and correcting a historical anomaly. The Lumbee are a well-documented, self-governing people. It’s time to treat them as such."

One of the persistent, though often unspoken, concerns raised by opponents of Lumbee recognition has historically been the potential for tribal gaming (casinos). However, proponents of the bill emphasize that the legislation itself does not automatically grant gaming rights. Any tribal gaming would still be subject to the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) and state-tribal compacts, requiring extensive negotiation and regulatory oversight. For the Lumbee, the primary motivation for recognition is not gaming, but access to essential services and the restoration of their inherent sovereignty.

Resilience and Hope

Despite the enduring challenges, the Lumbee Tribe remains remarkably resilient. Their cultural institutions, such as the Lumbee Tribal Council, the Lumbee Cultural Center, and the annual Lumbee Homecoming, serve as powerful anchors for community identity and pride. They have established their own health clinics, educational programs, and economic development initiatives, often with limited resources, showcasing their profound capacity for self-sufficiency.

"Our spirit has never been broken," Chairman Lowery asserts. "We have always been here, we have always been Lumbee, and we will continue to fight for what is rightfully ours. This recognition isn’t just about money; it’s about justice, about honoring our ancestors, and about securing a brighter future for our children."

The fight for full federal recognition is a testament to the Lumbee Tribe’s unwavering determination. It is a story not only of bureaucratic hurdles and legislative battles but also of cultural preservation, community strength, and the enduring quest for equity and dignity. As the Lumbee Recognition Act moves through Congress, the hopes of tens of thousands of Lumbee citizens rest on the promise that, finally, after more than a century, their identity will be fully acknowledged, and the cruel joke of 1956 will at last be undone. The long wait for justice continues, but the Lumbee remain steadfast in their pursuit of a recognition that is long overdue.