Echoes of the Brazos: The Enduring Legacy of the Waco Tribe

The name "Waco" conjures images for many: a central Texas city, a vibrant university town, perhaps even the site of a tragic modern confrontation. But long before the city lights glowed along the Brazos River, this fertile crescent was home to a people whose very name became synonymous with the land: the Waco tribe. Their story, rich in cultural distinctiveness, resilience, and profound loss, is an essential, if often overlooked, chapter in the complex tapestry of Native American history and the shaping of the American West.

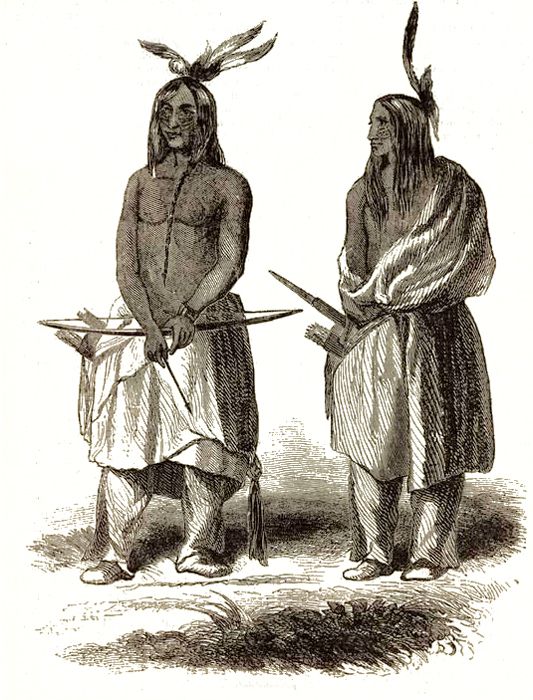

The Waco, or as they called themselves, the "Hueco" or "Huaco," were a distinct yet integral part of the larger Wichita confederacy, a group of Caddoan-speaking tribes who dominated the Southern Plains and Cross Timbers region of what is now Texas and Oklahoma. Unlike many Plains tribes solely focused on the buffalo hunt, the Waco were a fascinating blend of sedentary agriculturalists and skilled nomadic hunters. Their strategic location along the Brazos and Bosque rivers, particularly near the confluence where modern Waco now stands, afforded them access to rich farmlands, abundant game, and vital trade routes.

A Culture Rooted in the Land

Life for the Waco revolved around the rhythm of the seasons and the bounty of the land. Their villages, often fortified and strategically located, could house hundreds, sometimes thousands, of individuals. At the heart of their settlements were their distinctive conical or dome-shaped grass houses, a hallmark of the Wichita people. These marvels of engineering, made from a framework of cedar poles and thatched with tightly bound prairie grass, were surprisingly spacious, insulated, and durable, capable of withstanding the harsh Texas weather. Early Anglo-American observers marveled at their construction, noting their warmth in winter and coolness in summer.

Agriculture was the cornerstone of Waco society. They cultivated vast fields of corn, beans, squash, and pumpkins, demonstrating an advanced understanding of crop rotation and irrigation. The fertile river bottoms provided ideal conditions for their staple crops, ensuring a stable food supply. This agricultural prowess was complemented by their skill as hunters. While not exclusively buffalo hunters like the Comanche, the Waco regularly embarked on seasonal hunts for bison, deer, and other game, using bows and arrows, lances, and corralling techniques. Gathering wild edibles like pecans, berries, and roots further diversified their diet.

Trade was also vital. Situated at a crossroads, the Waco engaged in extensive networks, exchanging their agricultural produce, tanned hides, and crafted goods with other tribes, including the Comanche to the west and the Caddo to the east. This interaction fostered not only economic exchange but also cultural diffusion, cementing their place as a significant regional power. Socially, the Waco were organized into clans, with leadership often hereditary but also based on merit and wisdom. Their spiritual beliefs were deeply connected to the natural world, honoring the forces that sustained their lives and the spirits that inhabited the land.

The Inevitable Collision: Spanish, French, and Anglo Encounters

The relative peace and prosperity of the Waco began to unravel with the arrival of European powers. Initial encounters with the Spanish in the 18th century were marked by a mixture of trade and conflict, as Spain sought to establish missions and control the vast territory. However, it was the French, approaching from Louisiana, who established more significant trade relations, exchanging firearms and other goods for furs and hides, subtly altering the balance of power among Native groups.

Yet, it was the relentless westward expansion of Anglo-American settlers in the early 19th century that marked a profound and tragic turning point for the Waco. As Stephen F. Austin’s colonies began to spread across Texas, the settlers coveted the very lands that had sustained the Waco for generations. The cultural clash was immediate and irreconcilable. Settlers viewed the land as empty and ripe for exploitation, while the Waco considered it their ancestral home, imbued with history and spiritual significance.

The Battle of the Waco Village and Its Aftermath

The most devastating blow to the Waco’s independent existence came in 1829, or perhaps early 1830, when a pivotal and brutal clash occurred. A force of Anglo-American settlers, led by Captain John H. Moore, launched a surprise attack on the main Waco village, located near present-day Waco, Texas. Accounts from the time describe a swift and merciless assault. The Texans, seeking to break the power of the Native tribes and open up land for settlement, targeted the heart of the Waco community. The village was burned, and many Waco, including women and children, were killed.

This was not merely a skirmish; it was a deliberate act of territorial assertion, sending a clear message that the traditional way of life for the Waco and other tribes was no longer tolerated. The Battle of the Waco Village, though perhaps not as widely known as other frontier conflicts, was a devastating blow from which the tribe never fully recovered its former strength and autonomy in their ancestral lands. It forced the Waco to abandon their primary village, pushing them further west and north, into increasingly contested territories.

Displacement, Disease, and the Path to Oklahoma

In the wake of the attack, the Waco found themselves caught in an ever-tightening vise. They faced not only the advancing tide of Anglo-American settlers but also pressure from powerful Plains tribes like the Comanche, who were themselves being pushed westward and often raided the more settled Waco for horses and supplies. Disease, particularly smallpox and cholera, introduced by Europeans, ravaged their communities, for which they had no natural immunity. Their population, once numbering in the thousands, dwindled dramatically.

Despite repeated attempts to negotiate treaties with the Republic of Texas and later the State of Texas, the outcome was always the same: further loss of land and increasing marginalization. The Treaty of Council Springs in 1846, while not directly involving the Waco, was indicative of the broader policy of pushing tribes westward. By the mid-19th century, the Waco, along with other Wichita-affiliated tribes, were forced onto small, temporary reservations in Texas, such as the Brazos Reservation. These were inadequate and short-lived solutions, plagued by settler encroachment and hostility.

Ultimately, the inevitable came in 1859, when the remaining Waco, along with their Wichita kin, were forcibly removed from Texas to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The journey was fraught with hardship, starvation, and disease, a tragic pattern repeated for countless Native American tribes. In Oklahoma, they were settled on lands near the Washita River, far from their ancestral home on the Brazos.

Life in Indian Territory and the Enduring Legacy

Life in Indian Territory was a profound adjustment. Stripped of their traditional lands, their agricultural practices disrupted, and their hunting grounds diminished, the Waco struggled to adapt. They faced immense pressure to assimilate into Anglo-American society, to abandon their language, culture, and spiritual practices. The Dawes Act of 1887, which broke up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, further eroded their cultural fabric and economic independence.

Despite these immense challenges, the spirit of the Waco endured. They maintained their identity, intermarrying with other Wichita-affiliated tribes, strengthening their collective resolve. They held onto fragments of their language, their stories, and their understanding of the world, passing them down through generations.

Today, the descendants of the Waco people are federally recognized as part of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes (Wichita, Keechi, Waco, and Tawakoni), headquartered in Anadarko, Oklahoma. This modern tribal nation represents the resilience of a people who faced unimaginable adversity. They are actively engaged in cultural preservation efforts, including language revitalization programs, historical education, and the celebration of their rich heritage.

While the physical village of the Waco tribe on the Brazos River is long gone, its echoes resonate. The city of Waco, Texas, stands as a constant reminder of the original inhabitants of that land. Efforts by historians, archaeologists, and the Waco descendants themselves continue to shed light on their story, ensuring that their contributions to Texas history and their enduring legacy are not forgotten. The Waco tribe’s journey from flourishing agriculturalists on the banks of the Brazos to a resilient, unified nation in Oklahoma is a powerful testament to survival, adaptation, and the unwavering strength of cultural identity in the face of profound change. Their story compels us to remember the rich and complex history that shaped our shared landscape, and to honor the enduring spirit of the original guardians of the land.