Building Hope, Brick by Brick: The Enduring Legacy of America’s Works Progress Administration

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

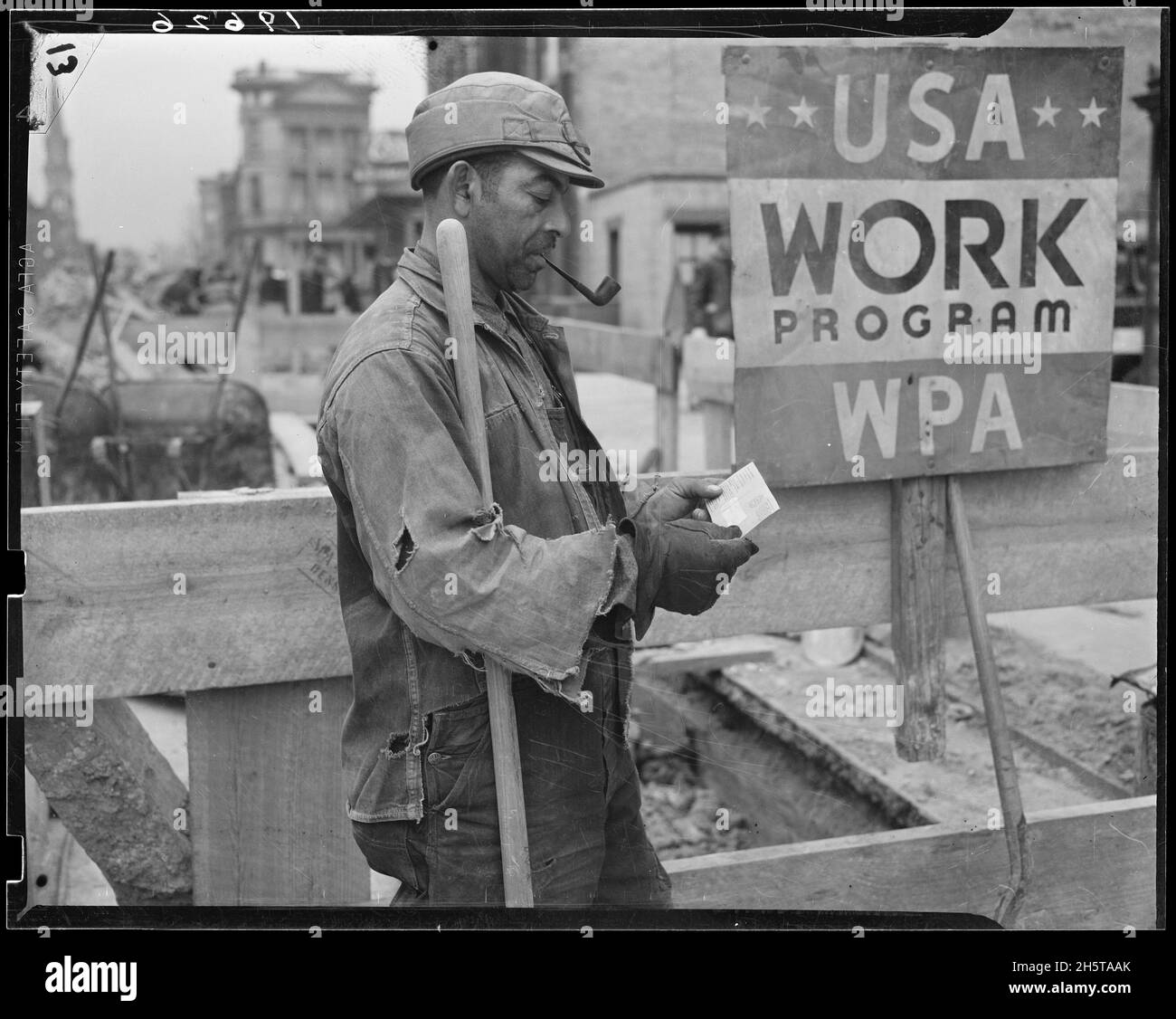

In the darkest hours of the Great Depression, when a quarter of the American workforce stood idle, and the very fabric of the nation seemed to fray, a radical idea took root. It was an idea not just of relief, but of purpose; not just of handouts, but of dignity through work. This was the genesis of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a monumental federal program that, from 1935 to 1943, transformed the physical and cultural landscape of the United States, leaving an indelible mark that resonates even today.

The year 1935 was a time of profound despair. The stock market crash of 1929 had plunged the nation into an economic abyss, leaving millions jobless, homeless, and hopeless. Shantytowns known as "Hoovervilles" dotted the urban landscape, a stark testament to the failure of existing policies. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected on a promise of a "New Deal," understood that more than just economic policy was needed; the nation’s spirit had to be rekindled.

"Give a man a dole," declared Harry Hopkins, the astute and compassionate social worker whom Roosevelt appointed to lead the WPA, "and you save his body but destroy his spirit. Give him a job and you save both body and spirit." This philosophy became the bedrock of the WPA. Unlike earlier relief efforts that often involved direct cash assistance, the WPA aimed to put people to work on public projects, injecting much-needed money into the economy while simultaneously building vital infrastructure and fostering a sense of national unity and purpose.

A Nation Rebuilt: The Physical Legacy

The scale of the WPA was staggering. Over its eight-year existence, the agency employed an average of 2 million people annually, peaking at 3.3 million in 1938. In total, more than 8.5 million Americans found work through the WPA. With an initial budget of nearly $5 billion – an astronomical sum at the time – the WPA launched an unprecedented construction spree that literally rebuilt America from the ground up.

Its primary focus was public works. WPA workers constructed or improved over 650,000 miles of roads, enough to circle the Earth more than 26 times. They built 78,000 bridges, connecting communities and facilitating commerce. Across the country, 125,000 public buildings – schools, hospitals, post offices, courthouses, and libraries – rose from the ground or were meticulously renovated. They also developed 8,000 parks, creating recreational spaces for urban populations.

Think of it: if you’ve ever driven on an old highway that seems particularly well-engineered, admired the sturdy brickwork of a historic post office, or strolled through a venerable park with hand-laid stone pathways, there’s a significant chance you’ve encountered the handiwork of WPA laborers. From the majestic Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood in Oregon to the iconic San Antonio River Walk in Texas, and countless smaller, essential projects in every state, the WPA’s physical legacy is ubiquitous and enduring.

These weren’t just "make-work" projects. They were carefully planned initiatives addressing genuine public needs, often in areas underserved by private enterprise. The projects provided vital infrastructure that would serve the nation for decades, proving that government investment could be both efficient and impactful.

Beyond the Concrete: The Federal Project Number One

Perhaps the most revolutionary, and certainly the most unique, aspect of the WPA was its commitment to the arts. Under the umbrella of "Federal Project Number One," the WPA established five groundbreaking programs: the Federal Art Project, the Federal Music Project, the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Writers’ Project, and the Historical Records Survey.

In a society where artists were often seen as a luxury, the WPA boldly declared that they, too, deserved work and dignity. "Artists must eat too," proclaimed Harry Hopkins. This initiative employed tens of thousands of struggling artists, musicians, actors, and writers, many of whom would later become celebrated figures in American culture.

- Federal Art Project: Commissioned over 100,000 artworks, including murals for public buildings (many still visible in post offices and courthouses), sculptures, and posters. It established community art centers, making art accessible to ordinary Americans for the first time. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Jacob Lawrence were among those who found employment and honed their craft.

- Federal Music Project: Employed musicians, composers, and music teachers, forming orchestras, bands, and choirs that performed for millions, often for free, bringing classical music and folk traditions to remote areas.

- Federal Theatre Project: Staged thousands of plays, including innovative "Living Newspapers" that dramatized current events, fostering critical public discourse. It employed actors, directors, stagehands, and playwrights like Orson Welles and John Houseman. The project was controversial for its progressive themes but played a vital role in developing American theater.

- Federal Writers’ Project: Perhaps one of the most lasting cultural achievements, this project produced over 1,200 books and pamphlets, including detailed guidebooks for every state, offering invaluable insights into local history, culture, and geography. Most famously, it collected over 2,300 first-person narratives from former enslaved people, preserving a critical, often overlooked, chapter of American history. This monumental undertaking gave voice to those long silenced, providing an unparalleled oral history of slavery.

- Historical Records Survey: Documented historical records across the nation, making vast amounts of archival material accessible to researchers and the public.

These cultural projects were not merely about employment; they were about affirming the value of art and culture to the national identity, democratizing access to the arts, and preserving a rich tapestry of American experience that might otherwise have been lost.

Beyond the Headlines: Diverse Impacts

While infrastructure and the arts were the WPA’s most visible facets, its reach extended into countless other areas. Women, often overlooked in public works, found employment in sewing rooms, making garments for the needy, or in school lunch programs, providing nutritious meals to children. Youth were engaged in projects through the National Youth Administration (NYA), a related New Deal program. The WPA also funded numerous research projects, compiling data that informed future social and economic policies.

For the millions who worked for the WPA, it offered more than just a paycheck; it provided a sense of purpose and self-worth. In an era when the unemployed were often stigmatized, the WPA offered a path to dignity. It put food on tables, kept families together, and reignited hope in communities ravaged by economic collapse.

Criticisms and Controversies

Despite its successes, the WPA was not without its critics. Opponents, often conservative politicians and business leaders, derided it as "boondoggling" – engaging in wasteful, unnecessary work. They labeled it "We Piddle Around" or "Wasteful Political Agency." Concerns were raised about the cost, the expansion of federal power, and accusations of political patronage. Some argued that WPA wages, while low, sometimes competed with private sector jobs.

However, proponents countered that even seemingly trivial projects, such as raking leaves or painting curbs, served a crucial purpose by providing income and maintaining morale during a crisis. In many cases, the "wasteful" projects were simply smaller, localized efforts that, collectively, made a significant difference.

The WPA’s Enduring Legacy

The outbreak of World War II effectively ended the WPA. As the nation mobilized for war, the need for public works jobs dwindled, replaced by the demands of the defense industry. By 1943, the WPA was formally dissolved, its mission accomplished by a booming wartime economy.

Yet, its legacy endures. Physically, countless roads, bridges, schools, and public buildings stand as monuments to the labor and foresight of the WPA. Culturally, its art, music, theater, and written works continue to enrich American life, offering unique perspectives on a pivotal era. The WPA Slave Narratives, in particular, remain an invaluable historical resource.

Beyond the tangible, the WPA fundamentally shifted the American understanding of government’s role. It demonstrated that in times of crisis, the federal government could act as an employer of last resort, stimulating the economy, providing essential services, and restoring human dignity. It laid a significant part of the groundwork for the modern social safety net and the concept of public investment in infrastructure.

The Works Progress Administration was more than just a jobs program; it was an audacious act of national self-preservation. It taught America that even in its darkest hour, by putting its people to work, it could rebuild its foundations, rekindle its spirit, and construct a future, brick by painstaking brick. Its story remains a powerful reminder of resilience, innovation, and the enduring power of collective action.