Echoes in Adobe: The Enduring Legacy of California’s Missions and Presidios

California, a land synonymous with dreams, innovation, and a vibrant, forward-looking culture, holds within its very foundations the echoes of a distant past. Beyond the glittering skylines and sun-drenched beaches lies a network of ancient adobe walls, quiet courtyards, and weathered bell towers that tell a complex, often brutal, story of encounter, ambition, and survival. These are the Spanish missions and presidios – the twin pillars of Spain’s colonial enterprise in Alta California, which, though long past their active service, continue to shape the state’s identity, stir historical debate, and stand as powerful, often contradictory, monuments to a pivotal era.

To understand California, one must first understand these outposts, which were not merely buildings but living, breathing engines of empire, designed to conquer not just land, but souls. Their very existence was born from a geopolitical chess match, as Spain, concerned by the encroaching presence of Russian fur traders from the north and British explorers from the sea, sought to solidify its claim on the vast, largely unexplored territories of what is now the American Southwest. The strategy was clear: establish a chain of self-sufficient religious communities (missions) to convert the indigenous populations and civilize them into Spanish subjects, protected and supported by military garrisons (presidios) that would secure the frontier.

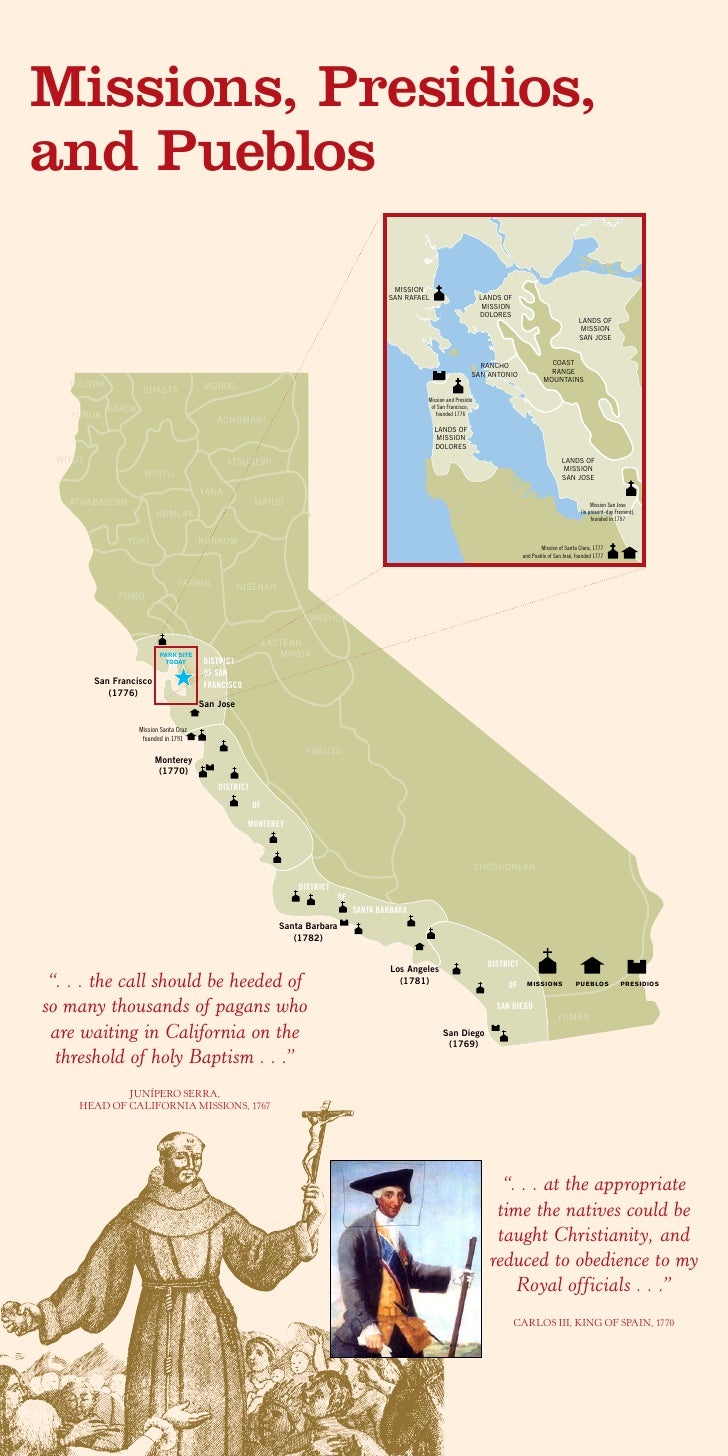

The mission system in Alta California officially began in 1769 with the arrival of Father Junípero Serra, a zealous Franciscan friar, and Gaspar de Portolá, a military governor. Serra, with an unshakeable conviction in his divine purpose, planted the first cross at San Diego, establishing Mission San Diego de Alcalá. This act marked the beginning of a relentless expansion that would, over the next 54 years, see 21 missions stretch a thousand miles along the coast, from San Diego in the south to Sonoma just north of San Francisco Bay. Each mission was strategically placed roughly a day’s journey apart, connected by the legendary "El Camino Real" (The Royal Road), a route still celebrated today.

The missions were ambitious endeavors, designed to be self-sufficient agricultural and industrial centers. Indigenous peoples, often referred to as "neophytes" by the Spanish, were drawn into or, in many cases, coerced into these communities. Under the tutelage of the Franciscan padres, they were taught European farming techniques, introduced to new crops like wheat and grapes, and instructed in trades such as carpentry, weaving, and blacksmithing. The iconic mission architecture, with its whitewashed adobe walls, red tile roofs, and graceful archways, was largely built by indigenous labor, a testament to their skill and the immense demands placed upon them.

Life within the mission walls was strictly regimented. Days began and ended with prayer, punctuated by hours of labor in the fields, workshops, or kitchens. The padres, often the sole Europeans for miles, wielded immense authority, acting as spiritual leaders, educators, and administrators. Their goal was nothing less than the complete transformation of indigenous life, replacing ancestral beliefs and practices with Catholicism and Spanish customs. While some conversions were undoubtedly sincere, many indigenous individuals found themselves trapped in a system that offered little freedom and often resorted to corporal punishment for infractions or attempts to escape.

However, the romanticized image of idyllic mission life, often depicted in early 20th-century art and literature, masks a darker reality. For the indigenous peoples, the arrival of the Spanish heralded an era of profound cultural disruption and demographic catastrophe. They lost their ancestral lands, their spiritual practices were suppressed, and their traditional ways of life were dismantled. Perhaps most devastating was the introduction of European diseases – measles, smallpox, and influenza – against which they had no immunity. Thousands perished, their populations decimated within generations. The conditions in the missions, often overcrowded and unsanitary, exacerbated the spread of these illnesses. Historian Steven W. Hackel notes that "The missions were not places of peace and plenty for all who lived there. They were also places of coercion, disease, and death for thousands of California Indians."

Complementing the missions, and equally vital to the Spanish colonial project, were the presidios. These fortified military garrisons served multiple critical functions. Primarily, they were defensive strongholds, protecting the missions and nascent Spanish settlements from both foreign incursions and indigenous resistance. The four main presidios in Alta California were established at San Diego (1769), Monterey (1770), San Francisco (1776), and Santa Barbara (1782). Each was strategically located to control key harbors and fertile lands.

Beyond defense, the presidios were administrative centers. They housed the provincial governors, treasury officials, and served as the primary points of contact for communication with Mexico City. Soldiers stationed at the presidios were responsible for maintaining order, apprehending runaway neophytes, and providing escorts for the padres and supply convoys traversing El Camino Real. While the missions focused on spiritual conversion, the presidios were the embodiment of Spanish secular authority and military power. Their presence underscored the fact that Spain’s claim to California was backed by force.

Life in the presidios, though different from the missions, was also arduous. Soldiers, often from Mexico, lived under harsh conditions, frequently receiving irregular pay and enduring long periods of isolation. Yet, these garrisons also became small, burgeoning communities, attracting civilian settlers, artisans, and merchants, laying the groundwork for future California cities. The interdependency between missions and presidios was absolute: the missions provided food and supplies for the soldiers, while the presidios offered protection and enforced the mission system.

The indigenous response to this colonial imposition was not monolithic. While many were compelled to enter the missions, others resisted fiercely. The Kumeyaay people of San Diego, for instance, launched a major revolt in 1775, burning Mission San Diego de Alcalá and killing Father Luis Jayme. The Chumash Revolt of 1824, involving several missions, demonstrated a coordinated effort to reclaim their freedom. These acts of resistance, along with countless individual escapes and acts of defiance, highlight the agency and resilience of indigenous peoples in the face of overwhelming odds. Their stories are increasingly being brought to the forefront, challenging the one-sided narratives that dominated historical accounts for centuries.

The Spanish mission and presidio system ultimately began to unravel with Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821. The new Mexican government, viewing the missions as an anachronism and an impediment to economic development, initiated a process of secularization in the 1830s. Mission lands were redistributed, often to powerful Mexican Californio families, and the indigenous populations were ostensibly freed, though many found themselves landless and disenfranchised, their traditional social structures irrevocably damaged. The presidios, too, lost their strategic importance as the frontier shifted and Mexico’s focus turned inward.

By the time California became part of the United States in 1848, many of the mission and presidio structures were in ruins, plundered for their materials or left to decay. However, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a powerful "Mission Revival" movement. Driven by romanticism and a desire to create a distinct California identity, efforts were made to restore and preserve these historic sites. Architects emulated the mission style, leading to a ubiquitous aesthetic that still defines much of California’s public and private architecture. Today, the 21 California missions are popular tourist attractions, historical landmarks, and active Catholic parishes, drawing millions of visitors annually. The former presidios, while less visually unified due to subsequent urban development, often mark the historic hearts of major cities like San Francisco, Monterey, and San Diego.

Yet, the legacy of the missions and presidios remains a subject of intense and necessary debate. For many, they represent the birthplace of California, symbols of faith, resilience, and architectural beauty. For others, particularly indigenous communities, they are painful reminders of conquest, cultural annihilation, and forced labor. The ongoing controversy surrounding the veneration of figures like Father Serra, who was canonized by the Catholic Church in 2015, underscores the deep divisions in how this history is perceived. Critics argue that celebrating Serra overlooks the devastating impact of his missions on native populations, while proponents emphasize his spiritual dedication and the challenges he faced.

Ultimately, the missions and presidios are not mere relics of the past; they are living testaments to the complex, often contradictory, forces that shaped California. They challenge us to look beyond simplistic narratives and confront the full spectrum of human experience – ambition and suffering, faith and coercion, creation and destruction. As we walk through their silent courtyards or gaze upon their enduring walls, we are compelled to remember that history is not a static list of dates and names, but a vibrant, contested story that continues to resonate, demanding our attention, our empathy, and our critical understanding. The echoes in adobe remind us that to truly know California is to embrace the intricate, often painful, layers of its past.