The Vanished Empire of the Susquehanna: A Chronicle of the Susquehannock Tribe

Beneath the placid surface of Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna River, where currents whisper through ancient valleys, lies the untold story of a powerful, vanished empire. The Susquehannock, a formidable Indigenous nation, once dominated this vast watershed, their longhouses stretching from the river’s headwaters to the Chesapeake Bay. Their saga is one of military prowess, strategic economic mastery, and ultimately, a tragic testament to the devastating forces of European colonization – disease, relentless warfare, and cultural annihilation. Their memory, etched into the very landscape they once commanded, serves as a poignant reminder of a vibrant civilization lost to the annals of time.

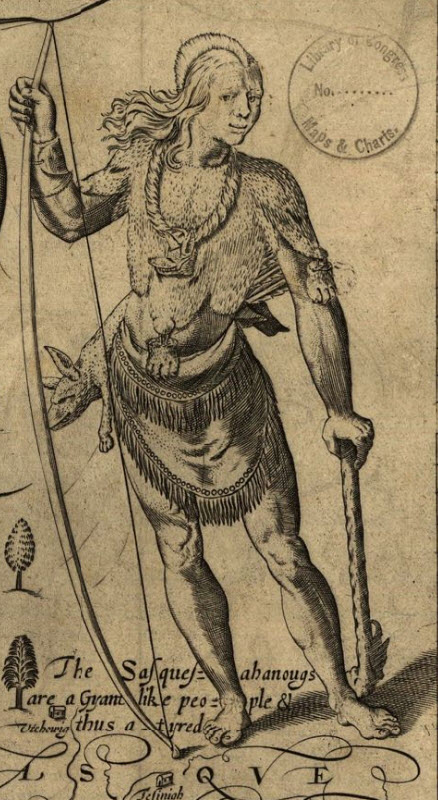

For centuries before the arrival of Europeans, the Susquehannock, an Iroquoian-speaking people, were the undisputed masters of their domain. Unlike their better-known Iroquoian cousins to the north, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Susquehannock developed a distinct identity, marked by their impressive stature, bellicose nature, and sophisticated societal structure. Early European accounts often described them as towering figures, physically imposing and fierce in battle, a reputation that instilled both respect and fear in their neighbors and colonial counterparts alike. Swedish explorer Peter Lindeström, in the mid-17th century, noted their "large, well-proportioned bodies" and their "warlike disposition," a description that painted a vivid picture of their formidable presence.

Their territory, centered around the fertile Susquehanna River Valley, was a strategic nexus of trade and agriculture. They cultivated extensive fields of corn, beans, and squash, supplementing their diet with abundant game from the forests and fish from the river. Their villages, often fortified with palisades, were hubs of activity, reflecting a well-organized society with strong leadership and communal living in traditional longhouses. They were not a monolithic entity but rather a confederacy of smaller groups, united by language, culture, and a shared interest in defending their lands and economic interests.

The Susquehannock’s strategic location made them pivotal players in the burgeoning European fur trade that swept across North America in the 17th century. Positioned between the rich beaver hunting grounds of the interior and the European trading posts along the coast – Dutch in New Netherland (New York), Swedes in New Sweden (Delaware), and later the English in Maryland and Virginia – they held immense leverage. They quickly adapted to the new economic realities, becoming adept intermediaries, trading beaver pelts for coveted European goods, most notably firearms. This acquisition of advanced weaponry further solidified their military dominance, allowing them to exert control over neighboring tribes like the Lenape and Nanticoke, who often paid tribute to the more powerful Susquehannock.

For a period, the Susquehannock skillfully played the European powers against each other. They forged strong alliances with the Swedes, who provided them with a consistent supply of guns and ammunition. This partnership allowed them to successfully repel incursions from the Dutch and, more significantly, to wage fierce and often victorious campaigns against their traditional enemies, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, who sought to expand their own fur trade empire southward. The mid-17th century represented the zenith of Susquehannock power, a time when they were perhaps the most militarily potent Indigenous nation in the Mid-Atlantic region.

However, the very forces that propelled them to power also sowed the seeds of their destruction. The fur trade, while bringing wealth and weapons, fundamentally altered their economy and way of life, making them increasingly dependent on European goods. More devastatingly, European contact introduced diseases against which Indigenous populations had no immunity. Smallpox, measles, and influenza swept through their communities with horrifying regularity, decimating their numbers. Historians estimate that their population, which may have been as high as 5,000-7,000 at the time of first contact, plummeted by as much as 90% within a few generations. A 1661 Maryland census, for instance, listed their fighting men at a mere 300, a stark indicator of their rapid demographic collapse.

Compounding the impact of disease was the relentless pressure of warfare. As their numbers dwindled, the Susquehannock found themselves increasingly isolated and vulnerable. The English colony of Maryland, initially a cautious ally, became a persistent adversary, often clashing over land claims and trade routes. But their most enduring and existential threat came from the revitalized Iroquois Confederacy, particularly the Seneca and Mohawk. Fueled by the Beaver Wars – a series of brutal conflicts over fur trade dominance – the Iroquois launched devastating raids against the Susquehannock, pushing them to their breaking point.

By the 1670s, the once-mighty Susquehannock were a shadow of their former selves. Weakened by disease and constant warfare, they were forced to abandon much of their ancestral territory. A pivotal moment occurred in 1675, when a remnant of the tribe, seeking refuge from Iroquois attacks, constructed a fort near Piscataway Creek in Maryland. Here, they found themselves caught in a violent frontier conflict with both the Iroquois and the English. A brutal siege by Maryland and Virginia militias, marked by treachery and the murder of several Susquehannock chiefs under a flag of truce, further decimated their ranks and shattered their spirit. Those who survived the siege scattered, many seeking asylum with the Iroquois, while others moved south to live among the Nanticoke or west towards the Ohio Valley.

A small, beleaguered group of Susquehannock, however, refused to abandon their ancestral lands entirely. These survivors, often referred to as Conestoga Indians, gathered in a village near present-day Lancaster, Pennsylvania. They were a peaceful, assimilated community, having adopted some European customs and living quietly under the protection of the colonial Pennsylvania government. They paid taxes, lived in houses rather than longhouses, and were considered harmless by their Quaker neighbors. Their numbers were few, perhaps no more than twenty individuals, a stark and sorrowful testament to the once-mighty nation they represented.

The year 1763 brought the final, brutal chapter to the Susquehannock story. The French and Indian War had recently concluded, but Pontiac’s War, an uprising of various Native American tribes against British expansion, was raging on the western frontier. This period was marked by intense anti-Indian sentiment among many white settlers, particularly those living on the frontier. In December of that year, a vigilante group known as the "Paxton Boys," fueled by paranoia, racial hatred, and a thirst for revenge against any Indigenous person, descended upon the peaceful Conestoga village.

On December 14, 1763, the Paxton Boys massacred six of the Conestoga, burning their homes and scalping their bodies. The remaining fourteen survivors, who had been away seeking safety, were rounded up by local authorities and placed in the Lancaster workhouse for their protection. However, two weeks later, on December 27, the Paxton Boys rode into Lancaster, broke into the workhouse, and brutally murdered the remaining Conestoga men, women, and children. They were scalped, dismembered, and left for dead. The massacre, carried out against a group explicitly under colonial protection, shocked many, including Benjamin Franklin, who wrote a scathing condemnation titled "A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County," describing the perpetrators as having "stained the Character of our Province in the Sight of the neighbouring Colonies and of all Europe."

The Conestoga Massacre marked the definitive end of the Susquehannock as a distinct tribal entity. It was a horrific act, not of war, but of unprovoked violence against a defenseless and assimilated community, symbolic of the ultimate failure of colonial governments to protect Indigenous peoples. Their name, once a byword for power and resilience, became synonymous with tragic extermination.

Today, the Susquehannock exist primarily in the archaeological record, in the pages of colonial documents, and in the place names that dot the Pennsylvania landscape – the Susquehanna River itself, Susquehannock State Park, and countless local designations that echo their lost presence. Archaeologists continue to unearth their village sites, revealing insights into their daily lives, their sophisticated craftsmanship, and their complex interactions with both the natural world and the encroaching European powers.

The story of the Susquehannock tribe is more than just a historical footnote; it is a profound and unsettling chronicle of the profound impact of colonization on Indigenous America. It speaks to the incredible resilience of a people who adapted, fought, and survived for generations against overwhelming odds, only to be ultimately consumed by forces beyond their control. Their tale reminds us of the fragility of even the most powerful nations in the face of disease, technological disparity, and unchecked prejudice. While their longhouses may have crumbled and their voices silenced, the ghost of the Susquehannock still echoes through the valleys of their ancestral river, a somber and necessary reminder of a vanished empire and the enduring importance of remembering those whose stories were almost erased.