Echoes in the Valley: Unearthing the Enduring Legacy of Mission Santa Inés

The California sun, a relentless artist, paints the Santa Ynez Valley in hues of gold and sage, illuminating rolling hills dotted with ancient oaks and burgeoning vineyards. Nestled within this idyllic landscape, just a stone’s throw from the whimsical Danish village of Solvang, stands a structure of profound historical and cultural weight: Mission Santa Inés. The 19th of California’s 21 Franciscan missions, its adobe walls and red-tiled roofs whisper tales of faith, endurance, conflict, and a complex legacy that continues to resonate through the heart of the Golden State.

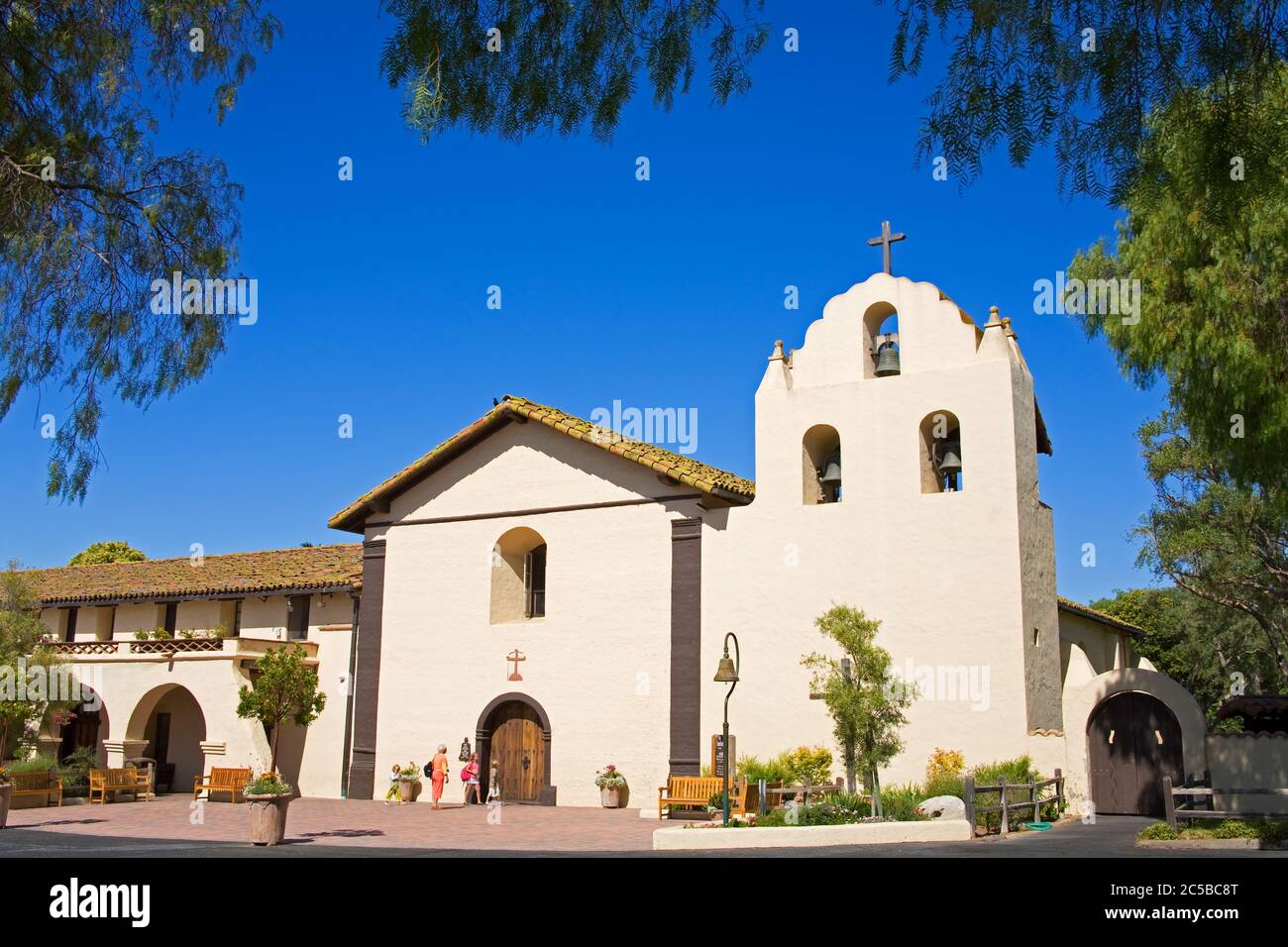

Stepping onto the grounds of Mission Santa Inés today is to enter a tranquil oasis, a stark contrast to the bustling modern world just beyond its gates. The air is still, save for the rustle of leaves and the distant chirping of birds. A towering bell tower, distinct in its simplicity, casts long shadows over a meticulously maintained garden, inviting contemplation. Yet, beneath this serene surface lies a history fraught with both noble intentions and devastating consequences, a microcosm of the entire California Mission system.

A Foundation in the Wilderness: The Founding Vision

The story of Mission Santa Inés begins on September 17, 1804, when Father Estévan Tapis, then President of the California Missions, dedicated the site. Named for Saint Agnes of Rome, a virgin martyr of the early Christian church, its establishment was strategically crucial. It was intended to bridge the significant geographical gap between Mission Santa Barbara to the south and Mission La Purísima Concepción to the north, facilitating travel and communication along El Camino Real. More importantly, it aimed to bring Christianity and the Spanish colonial way of life to the large population of Chumash people inhabiting the fertile Santa Ynez Valley.

The Franciscans, driven by a fervent desire to convert the indigenous populations and integrate them into the Spanish empire, envisioned the mission as a self-sufficient community. Here, the Chumash would learn European agricultural techniques, crafts, and the Spanish language, all while embracing Catholicism. The initial years saw rapid development. Churches, workshops, living quarters, and extensive agricultural fields were quickly established, transforming the landscape and the lives of the Chumash.

A Double-Edged Sword: Life for the Chumash

For the Chumash, the arrival of the Spanish was a cataclysmic event. While some initially embraced aspects of mission life, others were coerced or forced into the system. The mission offered a degree of protection from rival tribes and a steady supply of food, but it came at an immense cost. Traditional spiritual practices were suppressed, native languages discouraged, and the Chumash were subjected to a rigid, unfamiliar daily routine.

"The missions, while intended as centers of spiritual conversion and communal living, fundamentally disrupted the indigenous way of life," notes Dr. Elena Rodriguez, a historian specializing in California’s colonial period. "For the Chumash at Santa Inés, it meant a radical shift from a hunter-gatherer existence to an agrarian one, often involving forced labor and a loss of autonomy that profoundly impacted their culture and well-being."

Disease, brought by the Europeans, was perhaps the most devastating consequence. Lacking immunity to ailments like smallpox, measles, and influenza, Chumash populations at Santa Inés, as at other missions, were decimated. Despite these immense challenges, the Chumash demonstrated remarkable resilience, adapting, resisting in subtle and overt ways, and preserving elements of their culture even under oppressive conditions. Their labor, however, was the engine that powered the mission’s prosperity, from tending vast fields of wheat, corn, and beans to raising cattle and horses, and producing olive oil and wine.

The Test of Time: Earthquakes and Rebuilding

The early 19th century brought both peak prosperity and profound challenges to Mission Santa Inés. By 1810, the mission boasted a population of over 700 neophytes (converted natives) and a thriving agricultural enterprise. But nature, in its unpredictable fury, dealt a crippling blow. On December 21, 1812, a series of powerful earthquakes, known as the San Juan Capistrano or "Solstice" earthquakes, rocked Southern California.

Mission Santa Inés was severely damaged. The main church collapsed, many adobe structures crumbled, and the complex water system was destroyed. Undeterred, the community, under the leadership of Father Francisco Xavier Uria, embarked on an ambitious rebuilding effort. It took a decade, but a new, larger, and more robust church, the one largely seen today, was completed in 1817. This period of reconstruction highlights the incredible dedication and labor of the Chumash, who literally rebuilt their spiritual and physical home from the rubble.

Secularization and Decay: A Period of Neglect

The seeds of the mission system’s decline were sown with Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821. The new Mexican government, wary of the Franciscans’ influence and seeking to integrate mission lands into the secular economy, began a process of "secularization." In 1834, Mission Santa Inés was officially secularized. Its lands were gradually privatized, its cattle dispersed, and the Chumash, promised land and citizenship, often found themselves dispossessed and marginalized.

The mission fell into disrepair. Without the structured labor force and the Franciscan oversight, the adobe structures, vulnerable to the elements, began to crumble. Livestock roamed freely through decaying buildings, and the once-thriving agricultural fields lay fallow. For decades, the mission served as little more than a parish church for a dwindling congregation, a shadow of its former glory.

A brief glimmer of hope appeared in 1844 when Bishop Francisco García Diego y Moreno established California’s first seminary, Our Lady of Guadalupe, at Santa Inés. However, due to financial difficulties and the Mexican-American War, the seminary was short-lived, closing its doors in 1850. The mission continued its slow descent into ruin, a poignant symbol of a fading era.

A Century of Restoration: Rebirth from the Ruins

The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a turning point for Mission Santa Inés. A growing interest in California’s Spanish past, fueled by historical societies and preservationists, spurred efforts to save the decaying missions. In 1904, a significant milestone occurred when Archbishop John J. Cantwell of Los Angeles initiated a major restoration project. This included the rebuilding of the church’s façade and the bell tower, giving the mission much of its current appearance.

Further restoration efforts were undertaken throughout the 20th century, notably by the Capuchin Franciscans who arrived in 1924, and later by the Daughters of Charity, who played a crucial role in maintaining the mission and its grounds. These dedicated individuals painstakingly repaired adobe walls, restored artwork, and meticulously recreated elements of the mission’s original design, often relying on early photographs and historical accounts.

"The restoration of Mission Santa Inés is a testament to persistent human effort and a deep respect for history," says Father Michael Murphy, the current pastor. "It’s been a continuous process, almost a century in the making, and it reflects the commitment of countless individuals, from the early Franciscans to modern preservationists, to keep this sacred place alive."

The Modern Mission: A Living Legacy

Today, Mission Santa Inés stands as one of the best-preserved and most active of the California missions. It serves as an active Catholic parish, holding daily services and ministering to a vibrant community. Its museum houses a remarkable collection of artifacts, including religious vestments, artwork, and historical documents, offering visitors a tangible connection to its past.

The mission’s serene grounds, with their picturesque gardens, fountains, and the iconic bell tower, attract thousands of visitors annually. It has earned the moniker "Mission of the Passes" for its strategic location guarding both the San Marcos and Gaviota Passes, a reminder of its historical significance as a waypoint. Its proximity to Solvang, a popular tourist destination, also ensures a steady stream of curious travelers.

A Complex Heritage: Acknowledging All Voices

Yet, a journalistic examination of Mission Santa Inés cannot overlook the complex and often painful aspects of its heritage. While it represents a profound chapter in California’s development and a testament to the endurance of faith, it also symbolizes the devastating impact of colonization on indigenous peoples.

"For many of us, descendants of the Chumash, Mission Santa Inés evokes mixed emotions," shares Julia F. Brown, a representative of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. "It is a place where our ancestors were buried, where our culture was suppressed, but also where they survived and adapted. It’s a place of memory, of both sorrow and resilience, and it’s vital that its history is told in its entirety, acknowledging all perspectives."

This sentiment underscores the ongoing dialogue surrounding the missions, a conversation that seeks to reconcile their spiritual and architectural beauty with the human cost of their establishment. Mission Santa Inés, like its sister missions, is not just a relic of the past; it is a living monument to a pivotal, often contradictory, period in California’s story.

Conclusion: Echoes of Eternity

As the sun sets over the Santa Ynez Valley, casting long, golden shadows across the adobe walls of Mission Santa Inés, the echoes of its past seem to stir. The bells that once called the Chumash to prayer now toll for a modern congregation. The sturdy walls, rebuilt from ruin, stand as a testament to resilience.

Mission Santa Inés is more than just a historical site; it is a vibrant center of faith, a repository of art and culture, and a powerful symbol of the enduring human spirit. Its story is a mosaic of faith and forced labor, prosperity and poverty, destruction and rebirth. In its quiet grandeur, it continues to invite reflection, reminding us that history, in all its complexity, is never truly silent, but always whispering its truths to those who are willing to listen.