The Silent Revolution: How Sequoyah’s Syllabary Transformed the Cherokee Nation

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

Introduction: The Unlettered Genius

Imagine a nation, vibrant with oral traditions, complex in its governance, yet without a written word. Then, in a single generation, envision that nation achieving near-universal literacy, publishing its own newspaper, and codifying its laws, all thanks to the singular vision of one man. This is the extraordinary story of Sequoyah, a Cherokee polymath who, despite being illiterate himself, gifted his people a written language that sparked a cultural and political renaissance. His invention, the Cherokee Syllabary, stands as one of history’s most remarkable intellectual achievements, a testament to human ingenuity and a powerful symbol of resilience in the face of immense adversity.

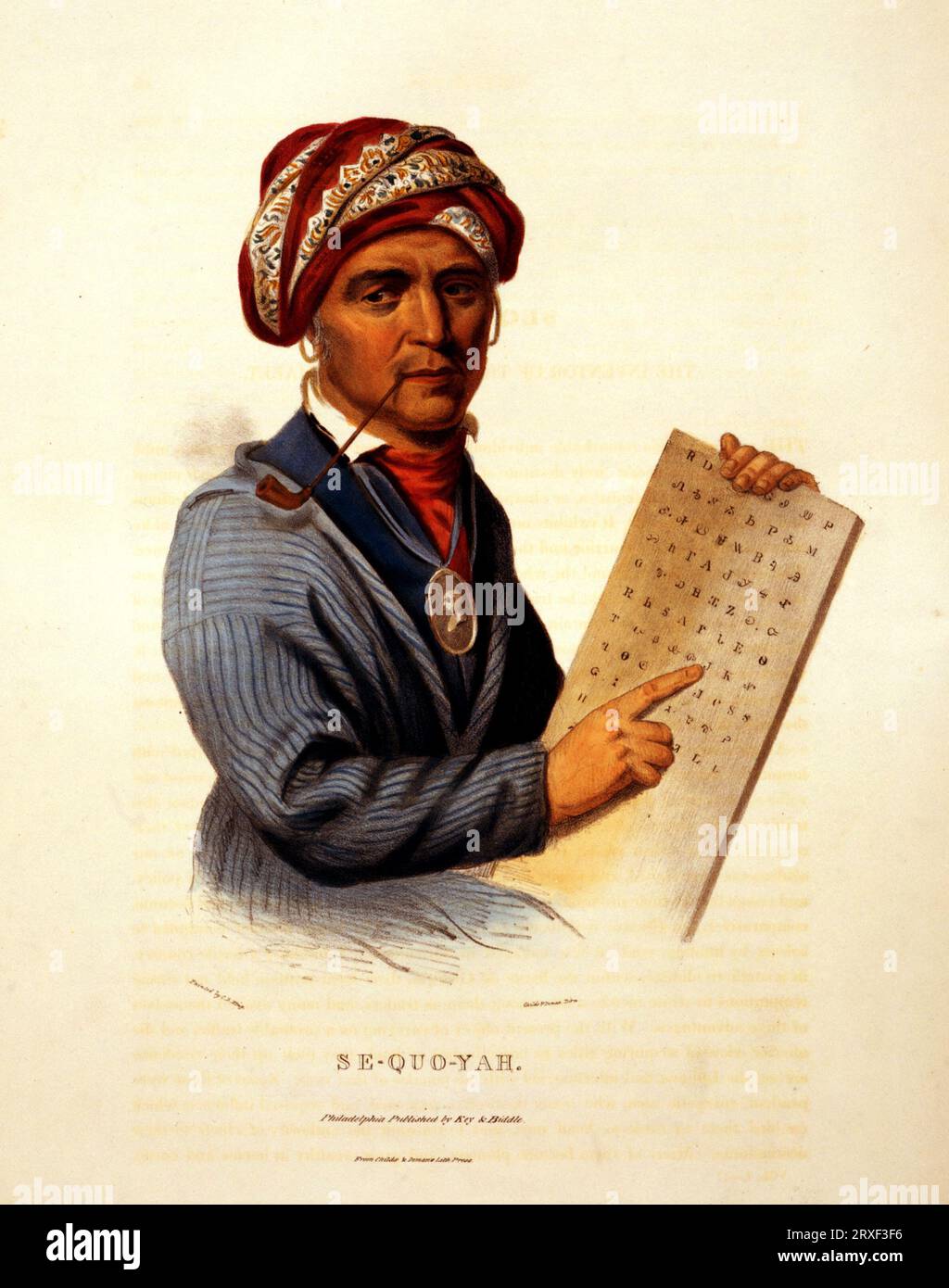

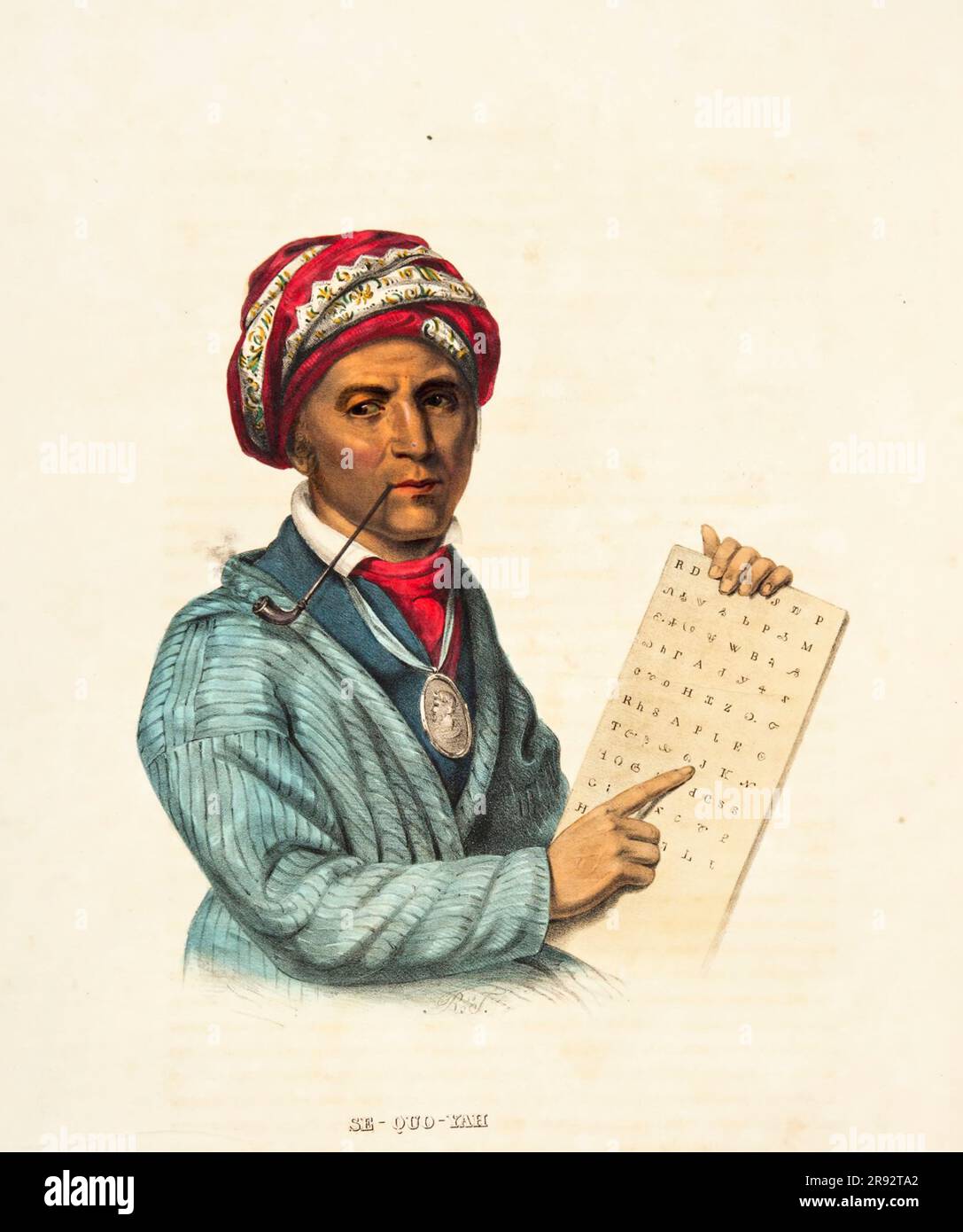

Born around 1770 in Tuskegee, Tennessee, to a Cherokee mother and a white trader father, Sequoyah (whose English name was George Gist or Guess) grew up immersed in Cherokee culture. He was a silversmith, a blacksmith, and later a soldier, but crucially, he never learned to read or write English. This lack of formal schooling, however, did not limit his perception of the profound power held by the "talking leaves" – the written documents he observed the white settlers using. It was this observation, coupled with a deep concern for his people’s future, that ignited his monumental quest.

The Genesis of an Idea: Unlocking the "Talking Leaves"

For centuries, the Cherokee language, Tsalagi, had been passed down orally, a rich tapestry of stories, laws, and knowledge communicated through speech. But as the Cherokee Nation increasingly engaged with American settlers, particularly concerning treaties and land disputes, the limitations of an exclusively oral tradition became glaringly apparent. Written documents, often misunderstood or misrepresented, held undeniable power.

Sequoyah recognized this imbalance. He saw that the white man’s ability to communicate across vast distances and through time, to record laws and agreements, gave them a significant advantage. He often mused with fellow Cherokee about the mystery of writing. "I have heard," he is quoted as saying, "that the white people can put their thoughts on paper and send them to people who are far away, and they will understand what is written. I want to learn how to do that."

Initially, Sequoyah’s understanding of written language was rudimentary. He believed, like many before him, that each word required a unique symbol. For years, he toiled in isolation, his friends and family often viewing his obsession with derision or concern, thinking he was losing his mind. He experimented with thousands of symbols etched onto bark, stone, and paper, attempting to capture the entirety of the spoken Cherokee language. This early phase was a period of intense trial and error, a lonely intellectual marathon.

The Breakthrough: A Symphony of Syllables

The turning point came when Sequoyah realized the insurmountable difficulty of creating a distinct character for every word. His genius lay in a pivotal conceptual leap: instead of symbols for words or individual letters, he would create symbols for syllables. He listened intently to spoken Cherokee, dissecting words into their constituent sounds. He discovered that the complex Cherokee language, despite its richness, was composed of a relatively small number of distinct phonetic syllables.

"After a year or more," Sequoyah later recounted, "I found that the words consisted of syllables, and I thought that if I could get the syllables, I would have the language." This simple yet profound realization was the key. He meticulously identified 85 distinct sounds, or syllables, that encompassed every word in the Cherokee vocabulary. He then designed a unique character for each syllable, drawing inspiration from English letters he saw in books, but assigning them entirely different phonetic values. For example, the English "R" became his symbol for "a."

By 1821, after twelve years of relentless dedication, Sequoyah had completed his syllabary. It was elegant in its simplicity and profound in its implications.

The Ultimate Test: A Daughter’s Triumph

The initial reception of Sequoyah’s invention was mixed. Many remained skeptical of this unlettered man claiming to have created a written language. To prove its efficacy, Sequoyah enlisted the help of his young daughter, Ayoka (or Ayokeh). He taught her the 85 characters, demonstrating how quickly and easily she could learn to read and write using his system.

A public demonstration was arranged. Sequoyah would leave the room, and other Cherokee speakers would dictate messages to Ayoka. Upon his return, he would read her written messages aloud, often with perfect accuracy, or vice-versa. The effect was electrifying. The Cherokee people, witnessing this miracle of communication unfold before their eyes, were astonished. The skeptics were silenced.

News of the syllabary spread like wildfire throughout the Cherokee Nation. Its phonetic nature made it incredibly intuitive to learn. Unlike the complex rules and inconsistencies of English orthography, the Cherokee Syllabary was remarkably consistent: each symbol always represented the same sound. An adult could learn to read and write within days, sometimes even hours.

A Nation Transformed: The Syllabary’s Impact

The adoption of the syllabary was nothing short of miraculous. Within a decade of its completion, the Cherokee Nation achieved a literacy rate that far surpassed that of their white American neighbors. It was a cultural explosion, a quiet revolution that reshaped every aspect of Cherokee life.

One of the most significant manifestations of this newfound literacy was the establishment of the Cherokee Phoenix (Tsalagi Tsu-le-hi) in 1828. Printed in New Echota, Georgia (the Cherokee Nation’s capital at the time), it was the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States, and notably, it was bilingual, featuring columns in both Cherokee (using the syllabary) and English. Edited by Elias Boudinot, a prominent Cherokee leader, the Phoenix became a vital tool for disseminating information, fostering national unity, and communicating the Cherokee perspective to the outside world.

The syllabary facilitated unprecedented levels of communication and organization within the Cherokee Nation. Laws and treaties could be recorded accurately. The Cherokee Constitution, adopted in 1827, was written in the syllabary. Religious texts, including the New Testament, were translated, deepening spiritual engagement. Schools were established, teaching the syllabary alongside other subjects. It empowered the Cherokee to articulate their grievances, assert their sovereignty, and document their history with precision.

As the historian Robert Conley noted, "The Cherokee Nation became the most literate nation in the world at that time, and it was all due to the genius of Sequoyah." This literacy was not merely a convenience; it was a cornerstone of Cherokee nation-building, a powerful assertion of their identity and self-determination in an increasingly hostile political landscape.

Against the Tide: Resilience Through Removal

The period following the syllabary’s invention was one of immense turmoil for the Cherokee. Despite their remarkable achievements in self-governance and cultural advancement, they faced relentless pressure from the United States government and the state of Georgia, driven by the insatiable demand for land, particularly after the discovery of gold on Cherokee territory. This culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the tragic forced relocation of the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes in 1838-1839, known as the Trail of Tears.

While the syllabary could not prevent this devastating act, it played a crucial role in helping the Cherokee navigate the crisis. It allowed for communication between dispersed families and communities during the forced march. Letters written in the syllabary provided solace, shared information, and helped maintain cultural cohesion amidst unimaginable suffering. It became a silent act of defiance, a testament to their enduring identity even as their lands were stripped away.

Sequoyah’s Later Years and Enduring Legacy

After witnessing the widespread adoption of his syllabary, Sequoyah continued to serve his people. He traveled extensively, acting as a diplomat and an emissary, helping to unite disparate Cherokee communities and promote literacy among those who had not yet learned his system. He also embarked on a quest to locate a "lost" band of Cherokee said to have migrated west long before the Removal, hoping to share his gift with them.

It was during this journey, in 1843, that Sequoyah died in San Fernando de Taos, New Mexico, far from his ancestral lands. His exact burial place remains unknown, a quiet end for a man whose life had such a thunderous impact.

Sequoyah’s legacy, however, is anything but silent. His syllabary remains a living language, taught in schools, used in publications, and cherished by the Cherokee people today. It is a source of immense pride, a tangible link to their ancestors, and a powerful symbol of their intellectual prowess and cultural resilience.

The giant redwood trees, Sequoia sempervirens, and the giant sequoia, Sequoiadendron giganteum, were named in honor of him, a fitting tribute to a man whose invention stood tall and brought light to his people. His achievement is recognized globally as a unique instance of a single individual, without prior literacy, creating a fully functional writing system.

Conclusion: A Light That Still Shines

Sequoyah’s story is more than just a historical account; it is a profound narrative of innovation, determination, and the transformative power of literacy. In a world that often sought to diminish and erase indigenous cultures, Sequoyah provided his people with a tool for self-preservation, self-expression, and self-determination. His syllabary did not just enable the Cherokee to read and write; it empowered them to define themselves, to record their history in their own words, and to navigate the complexities of a changing world on their own terms.

The silent revolution he ignited continues to resonate, a testament to the enduring genius of Sequoyah, the unlettered scholar who taught a nation to read, and in doing so, ensured its voice would never be silenced. His "talking leaves" continue to speak, a beacon of cultural survival and a perpetual source of inspiration.