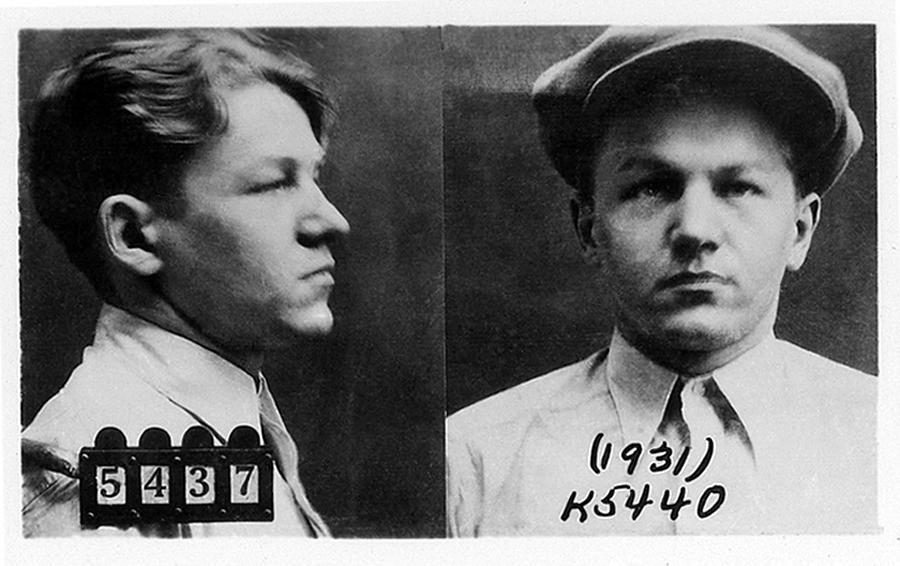

Baby Face Nelson: The Unsettling Paradox of a Name and a Legacy of Blood

In the annals of American crime, few figures embody such a stark paradox as Lester Joseph Gillis, better known by his chilling moniker: Baby Face Nelson. The name itself is a cruel joke, conjuring images of youthful innocence, a stark contrast to the short, stocky, and ferociously violent man who became one of the most feared bank robbers and cold-blooded killers of the Depression era. A contemporary of the more charismatic John Dillinger, Nelson lacked his partner’s public charm, replacing it instead with a hair-trigger temper and an unwavering willingness to unleash a hail of bullets on anyone who stood in his way, including federal agents. His brief but bloody reign as "Public Enemy No. 1" ended in a brutal, unprecedented shootout, cementing his place as a uniquely savage figure in the era of the gangster.

Born in Chicago in 1908 to Belgian immigrant parents, Lester Gillis’s early life offered few hints of the monstrous path he would carve. Growing up in the tough West Side, he was a small, quiet boy, a stark contrast to the larger-than-life persona he would later adopt. His descent into crime began early, a familiar story of petty theft escalating to more serious offenses. By his late teens, Gillis was already a seasoned burglar and car thief, serving time in various reformatories and eventually state prison. It was during these formative years in the criminal underworld that he honed his skills and, more ominously, developed the volatile temperament that would define his career.

The nickname "Baby Face" reportedly came from his relatively youthful appearance and small stature, often appearing younger than his years. However, those who knew him understood the irony. He despised the moniker, preferring "Little Shot," a testament to his ambition and a subtle nod to his proficiency with firearms. Despite his physical size, Nelson possessed an explosive rage that could erupt at the slightest provocation, turning him into a terrifying adversary. This internal fire, coupled with a deep-seated paranoia, made him unpredictable and exceptionally dangerous.

Nelson’s criminal career truly escalated in the early 1930s, as the Great Depression fueled a wave of bank robberies across the Midwest. He associated with various local gangs, participating in numerous heists that grew increasingly bold and violent. But it was his eventual partnership with John Dillinger that catapulted him onto the national stage. Dillinger, already a folk hero to some for his audacious escapes and charming persona, recognized Nelson’s unique brand of ruthlessness. While Dillinger might have tried to avoid bloodshed, Nelson reveled in it, often initiating shootouts unnecessarily, earning him a reputation as a madman even among his fellow criminals.

Their most infamous collaboration began after Dillinger’s dramatic escape from the Crown Point, Indiana, jail in March 1934. Nelson, along with Homer Van Meter, Pretty Boy Floyd, and others, formed the core of the new Dillinger gang. This short-lived but intense period saw them embark on a spree of high-profile bank robberies across multiple states, each one a testament to their daring and firepower.

The gang’s notoriety reached a fever pitch in April 1934, during the infamous shootout at the Little Bohemia Lodge in northern Wisconsin. The FBI, led by the tenacious Melvin Purvis, had received a tip-off about the gang’s whereabouts and descended on the remote resort. What followed was a chaotic and deadly exchange of gunfire. In the ensuing melee, Nelson’s true nature shone through with terrifying clarity. While most of the gang managed to escape through a hail of bullets, it was Nelson who single-handedly engaged a group of federal agents, killing FBI agent W. Carter Baum with a burst from his Thompson submachine gun. He then commandeered a car, shooting its occupants and using them as human shields to facilitate his escape. This incident marked a turning point; Nelson was no longer just a dangerous criminal but a cold-blooded killer of federal officers, earning him a permanent place at the top of the FBI’s most wanted list.

J. Edgar Hoover, the formidable director of the Bureau of Investigation (which would soon become the FBI), made it clear that Nelson was a priority. "Nelson," Hoover declared, "is perhaps the most vicious, trigger-happy hoodlum in the criminal history of the United States." The federal government mobilized an unprecedented effort to track him down, deploying agents across the country and utilizing every available resource.

After the Little Bohemia debacle, the Dillinger gang scattered. Nelson continued his bloody trajectory, often accompanied by his loyal wife, Helen Gillis, and fellow outlaw John Paul Chase. He continued robbing banks, his methods becoming even more brutal. He was known for his love of the Thompson submachine gun, which he wielded with deadly proficiency, often firing indiscriminately. His modus operandi involved overwhelming force and a complete disregard for human life, whether it be bank tellers, customers, or law enforcement. He was a man who preferred to shoot first and never ask questions.

The net began to tighten around the remaining members of the Dillinger gang. On July 22, 1934, John Dillinger himself was gunned down by federal agents outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago. With Dillinger’s death, the spotlight of the national manhunt shifted entirely to Baby Face Nelson. He was officially declared "Public Enemy No. 1," a title he held for a mere four months, but one he earned with an unparalleled trail of violence.

The chase for Nelson intensified, becoming a relentless cat-and-mouse game across the American heartland. He and his small entourage, consisting of Helen and John Paul Chase, were constantly on the move, relying on their wits, stolen cars, and a network of safe houses to evade capture. But the FBI’s pursuit was equally relentless, driven by the desire to avenge their fallen comrades and to finally bring down one of the era’s most dangerous criminals.

The final act of his bloody drama unfolded on November 27, 1934, in what would become known as the Battle of Barrington. Near the sleepy Illinois town, Nelson, accompanied by Helen and John Paul Chase, was driving a stolen car when they inadvertently encountered two FBI surveillance cars. The first encounter was brief, but Nelson, ever paranoid and quick to act, suspected they were law enforcement. He instructed Chase to follow them.

What happened next was an unprecedented, brutal firefight. As Nelson’s car pursued the FBI agents, they encountered another Bureau car carrying Agents Samuel P. Cowley and Herman Hollis. Nelson, recognizing the threat, sped past the FBI vehicle, then pulled sharply in front of it, forcing it to stop. He and Chase immediately opened fire with their powerful automatic weapons.

The ensuing gun battle was ferociously intense, fought at close range with devastating consequences. Nelson, a small man, was a whirlwind of motion, firing his custom-built .351 Winchester automatic rifle and a .45 pistol. Agent Hollis was killed almost instantly by a blast from Nelson’s rifle. Agent Cowley, a seasoned lawman, was shot 17 times but managed to return fire, striking Nelson multiple times in the legs and abdomen. Despite his severe wounds, Nelson continued to fight, demonstrating an almost superhuman resistance to pain. He reportedly even taunted Cowley, yelling, "I’ll kill you, you son of a bitch!"

In a desperate bid for survival, Nelson and Chase managed to disarm the mortally wounded Cowley. Nelson, bleeding profusely and barely able to stand, got behind the wheel of the agents’ bullet-riddled Ford V8, with Helen and Chase helping him. They drove off, leaving the dying Agent Cowley behind. Cowley would succumb to his injuries the following morning, making Nelson the only Public Enemy No. 1 in FBI history to kill two federal agents in a single engagement.

Nelson’s triumph was short-lived. He was mortally wounded, sustaining 17 bullet wounds from Cowley’s return fire. As Helen drove frantically through the night, Nelson’s condition rapidly deteriorated. He died in her arms later that evening, near a remote cemetery, bringing his violent career to an abrupt and ignominious end. Helen, ever loyal, dressed his body and wrapped it in a blanket, then dumped it in a ditch, hoping to obscure his identity. She then fled with Chase.

The next day, Nelson’s body was discovered, and his identity confirmed by fingerprints. The news of his death brought a collective sigh of relief from law enforcement and the public alike. Helen Gillis was later captured and served time for harboring her husband, while John Paul Chase was also apprehended and received a life sentence.

Baby Face Nelson’s legacy is not one of romanticized outlawry, but rather a chilling testament to unbridled violence and paranoia. He was a man consumed by his own rage, whose "baby face" hid a cold heart and a killer’s instinct. His brief reign as Public Enemy No. 1, culminating in the unprecedented double murder of federal agents, cemented his image as the most dangerous and ruthless of the Depression-era gangsters. His death, just months after Dillinger’s, marked a significant turning point in the FBI’s war on crime, signaling the end of an era when brazen bank robbers could terrorize the nation with relative impunity. Lester Joseph Gillis, the quiet boy from Chicago, became Baby Face Nelson, a name forever etched in infamy as a symbol of the era’s brutal criminal underworld.