Ephemeral Canvas, Eternal Healing: The Sacred Art of Navajo Sand Painting

In the vast, sun-drenched landscapes of the American Southwest, where ancient mesas pierce the sky and the wind whispers tales of creation, lies a profound and beautiful healing art form: Navajo sand painting. More than mere artistic expression, these intricate, vibrant creations are sacred tools, meticulously crafted as central components of complex healing ceremonies, embodying the very essence of the Diné (Navajo people’s name for themselves) philosophy of Hózhó – balance, harmony, and beauty.

Unlike most art forms intended for permanence, Navajo sand paintings are deliberately ephemeral. They are created, used, and then destroyed, their fleeting existence central to their power. This transient nature underscores a core Diné belief: the sacred energies invoked must be absorbed by the patient and then released back into the cosmos, preventing any lingering imbalance or misuse.

The Philosophy of Hózhó: The Guiding Principle

To understand Navajo sand painting, one must first grasp the concept of Hózhó. It is not simply "beauty" in an aesthetic sense, but a comprehensive worldview that encompasses physical, mental, spiritual, and social well-being. When an individual experiences illness, misfortune, or distress, it is believed that their Hózhó has been disrupted, leading to an imbalance with the natural and spiritual worlds. The purpose of the sand painting, within the larger framework of a chantway ceremony, is to restore this lost harmony, to bring the individual back into alignment with the Holy People (Diyin Diné’e) and the cosmic order.

"Our world is full of beauty, and we must strive to live in a way that reflects that beauty," a Navajo elder might explain. "When we are sick, it means we are out of balance. The sand painting helps us find our way back."

The Hataałii: Custodians of Ancient Knowledge

The creation and use of sand paintings are the domain of the hataałii, or medicine people (often translated as "singers" or "chanters"). These highly revered individuals undergo decades of rigorous training, memorizing vast oral traditions, intricate songs, prayers, and the precise designs of hundreds of sand paintings associated with specific chantways. Their knowledge is encyclopedic, encompassing not only the spiritual realm but also botany, anatomy, psychology, and astronomy. They are not merely artists; they are spiritual doctors, diagnosticians, and conduits for healing energy.

A hataałii determines which chantway, and thus which specific sand painting, is appropriate for a patient based on the nature of their illness, dreams, or circumstances. Each painting is a sacred map, a visual prayer tailored to the specific spiritual imbalance afflicting the individual.

The Ceremony: A Symphony of Healing

A sand painting is never created in isolation. It is an integral part of an elaborate, multi-day healing ceremony known as a "chantway" or "sing." These ceremonies can last from two to nine nights, involving extensive prayers, songs, rituals, and often the participation of family and community members. The sand painting is typically created on the floor of the ceremonial hogan (a traditional Diné dwelling), meticulously crafted over several hours, sometimes with the assistance of apprentices.

The hogan itself is a sacred space, oriented to the east to welcome the rising sun and positive energies. The preparation of the space, the gathering of materials, and the concentration of the hataałii all contribute to the potency of the healing ritual.

The Canvas of the Earth: Materials and Creation

The "canvas" for these sacred works is the earth itself, specifically the prepared dirt floor of the hogan. The "paints" are natural materials, carefully collected and ground into fine powders:

- White: Derived from white sandstone, gypsum, or pulverized yucca root.

- Blue: From blue sandstone, charcoal mixed with white, or sometimes corn pollen.

- Yellow: From yellow ochre or pulverized corn pollen.

- Black: From charcoal, manganese ore, or crushed dark minerals.

- Red: From red sandstone, crushed terracotta, or iron oxides.

Other elements like corn pollen, flower pollen, and ground minerals may also be incorporated for specific symbolic or energetic purposes.

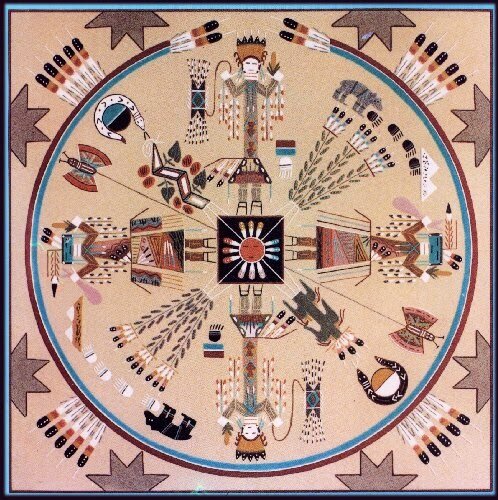

The process of creation is a deeply meditative and precise one. The hataałii, or assistants under their direct supervision, sit on the floor, allowing the fine, colored sands to flow between their fingers onto the prepared surface. They begin at the center, working outwards, adhering to strict traditional patterns and orientations. Each line, each color, each figure is imbued with profound symbolic meaning, representing deities (such as the Yeibichai or Holy People), natural phenomena, celestial bodies, animals, or mythological events that are part of the Navajo creation stories and healing narratives.

For example, figures often include anthropomorphic representations of the Holy People, such as Talking God (Haashch’éélti’í) or Calling God (Tó Neinilí). Elements like rainbows, lightning bolts, mountains, and sacred plants are common. The cardinal directions are always significant, with protective barriers often drawn on the eastern side, the direction from which positive energies enter. The designs are not mere illustrations; they are living blueprints of the universe, microcosms reflecting the macrocosm.

The Patient’s Immersion: A Transfer of Energy

Once the sand painting is complete, a crucial moment arrives. The patient, having been purified through prayers and other rituals, is led to the painting and instructed to sit directly upon its center. This act is not merely symbolic; it is believed to facilitate a direct transfer of healing energy from the sacred figures within the painting to the patient. The patient becomes one with the Holy People depicted, absorbing their strength, balance, and restorative power.

The hataałii then presses various parts of the patient’s body to corresponding parts of the figures in the painting, chanting prayers and songs that invoke the Holy People to remove the illness and restore harmony. The illness is seen as an impurity, an alien element that needs to be absorbed by the painting and then expelled.

The Ephemeral Act: Destruction and Release

Perhaps the most unique and profound aspect of Navajo sand painting is its deliberate destruction. After the ceremony is complete and the patient has absorbed the necessary healing energies, the painting is systematically erased, usually within a few hours of its creation. The sand is gathered and respectfully returned to the earth, often outside the hogan, away from human traffic.

This act of destruction is not an act of discarding; it is a powerful act of release. It signifies that the illness has been absorbed, the imbalance corrected, and the sacred energies have fulfilled their purpose. To keep the painting would be to retain the very illness it was created to banish, or to contain sacred power that should be allowed to dissipate back into the universe. The ephemeral nature underscores the belief that the healing is not in the physical object, but in the spiritual process and the transformation within the individual.

Challenges and Preservation in the Modern World

Navajo sand painting, like many indigenous traditions, faces challenges in the modern world. The extensive training required for a hataałii is demanding, and fewer young people are choosing this path. The oral tradition is vulnerable to the loss of fluent speakers. Furthermore, there is a constant tension between the sacredness of the art and the demands of tourism and commercialization.

Authentic, ceremonial sand paintings are never made for sale or for public display outside of their ritual context. The designs are considered sacred and are not to be replicated permanently or for profit. However, commercial "sand art" — often made with glue or in glass bottles, sold in gift shops – has proliferated. While these may be aesthetically pleasing, they are distinct from the sacred ceremonial paintings and do not carry the same spiritual significance or power. The Diné people work to educate the public about this crucial distinction, protecting the integrity of their sacred practices while allowing for cultural appreciation.

An Enduring Legacy of Harmony

Despite the challenges, Navajo sand painting continues to be a vibrant and vital part of Diné culture. It represents an enduring connection to ancestral wisdom, a profound understanding of the interconnectedness of all things, and a powerful testament to the healing capacity of art and spirituality.

In a world increasingly characterized by fragmentation and discord, the ancient practice of Navajo sand painting offers a timeless lesson: true healing extends beyond the physical, encompassing a holistic restoration of balance, beauty, and harmony – Hózhó – not just for the individual, but for their relationship with the entire cosmos. It is an art form that vanishes, yet its impact resonates eternally.