Guardians of the Grand Canyon: The Hualapai Tribe’s Sky-High Journey to Self-Determination

The Grand Canyon, a chasm of unparalleled majesty, carves a formidable scar across the Arizona landscape, drawing millions of awe-struck visitors each year. Yet, for all its geological grandeur, the Canyon is also a living testament to human resilience and an enduring cultural heritage. For thousands of years, long before it became a national park or a global tourist destination, this rugged, beautiful land was, and remains, the ancestral home of the Hualapai Tribe. Their story is one of profound connection to the land, of struggle against overwhelming odds, and of a remarkable modern journey towards self-determination, quite literally, on the edge of the world.

The name "Hualapai" itself, meaning "People of the Tall Pines," speaks volumes about their historical relationship with their environment. Their traditional territory, spanning over five million acres, stretched from the pine-clad plateaus of northern Arizona down to the Colorado River, encompassing diverse ecosystems that provided for their needs. They were skilled hunter-gatherers, intimately familiar with every plant, animal, and water source in their vast domain. Their deep knowledge of the land, passed down through generations, allowed them to thrive in an environment that outsiders often deemed inhospitable.

"Our ancestors walked this land for thousands of years," explains Lucille Watahomigie, a Hualapai elder, her voice carrying the wisdom of generations. "Their spirits are in the wind, in the rocks, in the flow of the Hualapai River. We must never forget that sacred connection."

This ancient way of life, however, faced an existential threat with the arrival of European explorers and American settlers in the 19th century. The lure of gold, land, and the promise of a "manifest destiny" brought waves of newcomers who saw the Hualapai’s ancestral lands as open territory to be claimed and exploited. Conflicts over resources, particularly water and grazing land, escalated into the Hualapai War of the 1860s. Though fiercely resistant, the Hualapai, outnumbered and outgunned, were eventually forced onto a small reservation established in 1883. This sliver of land, though a fraction of their original domain, became their enduring homeland, a place where they could begin to rebuild and preserve their unique culture, language (a Yuman language spoken by only a few thousand people worldwide), and traditions.

For over a century, the Hualapai lived largely in obscurity, their remote reservation grappling with the challenges common to many Native American communities: high unemployment, limited access to education and healthcare, and a constant struggle to maintain sovereignty in the face of federal and state pressures. The breathtaking canyon that defined their identity was largely inaccessible to them in economic terms, even as tourism boomed just outside their borders.

By the turn of the 21st century, the tribe faced a stark choice: continue to rely heavily on external aid and limited internal resources, or forge a bold new path towards economic independence. It was a path that would lead them, quite controversially, to the very edge of their ancestral canyon.

In 2007, the Hualapai Tribe unveiled a project that would forever change their destiny and the way the world experienced the Grand Canyon: the Grand Canyon Skywalk. This U-shaped, glass-bottomed bridge extends 70 feet out over the canyon rim, suspending visitors 4,000 feet above the Colorado River. The audacious feat of engineering, located at Grand Canyon West on the Hualapai Reservation, instantly became a global sensation.

The decision to build the Skywalk was not made lightly. It sparked intense debate within the tribe and among environmentalists. Some viewed it as a brilliant economic strategy, a way to leverage their unique asset – the Grand Canyon – for the benefit of their people. Others saw it as a potential desecration of sacred land, a commercialization of something profoundly spiritual.

"The Skywalk was not an easy decision," stated Tribal Chairman Damon Clarke in a recent interview, echoing sentiments often expressed by tribal leaders. "But it was a necessary one. For too long, our people suffered. We had to create opportunities for our children, to invest in our future, to build a self-sufficient nation. This allows us to do that, on our terms, on our land."

The economic impact of the Skywalk and the broader Grand Canyon West tourism complex has been transformative. What was once a remote, struggling community is now a thriving enterprise employing hundreds of Hualapai tribal members. Revenue generated from tourism has been channeled into vital services: improving schools, building new homes, expanding healthcare facilities, and investing in infrastructure like roads and water systems. Before the Skywalk, many Hualapai had to leave the reservation to find work; now, jobs are available within their community, allowing families to stay together and maintain their cultural ties.

Grand Canyon West, which now attracts over a million visitors annually, is more than just the Skywalk. It includes the Hualapai Ranch, offering horseback riding and cowboy experiences; a zipline for thrill-seekers; and the Hualapai Lodge in Peach Springs, serving as a gateway to the reservation. The tribe also operates Hualapai River Runners, the only Native American-owned and operated white-water rafting company on the Colorado River, offering unparalleled access to the canyon’s depths. These ventures collectively provide a diverse tourism experience that highlights not just the natural beauty of the canyon, but also the rich culture of its indigenous guardians.

"We are not just selling a view; we are sharing a piece of our heritage, our story, our home," says a Hualapai tourism manager, overseeing operations at Grand Canyon West. "It’s a respectful exchange, where visitors learn about our culture while contributing to our tribe’s future."

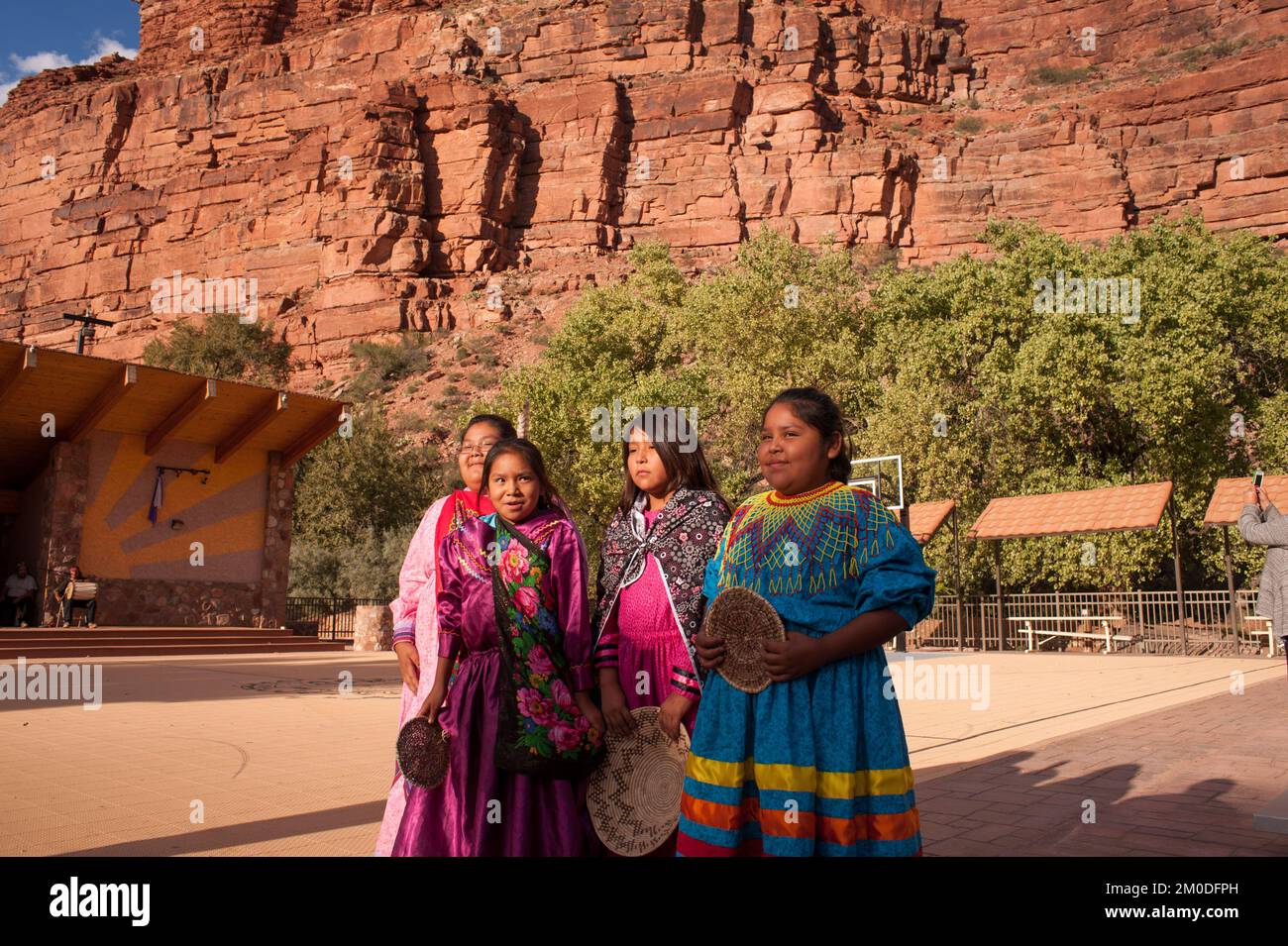

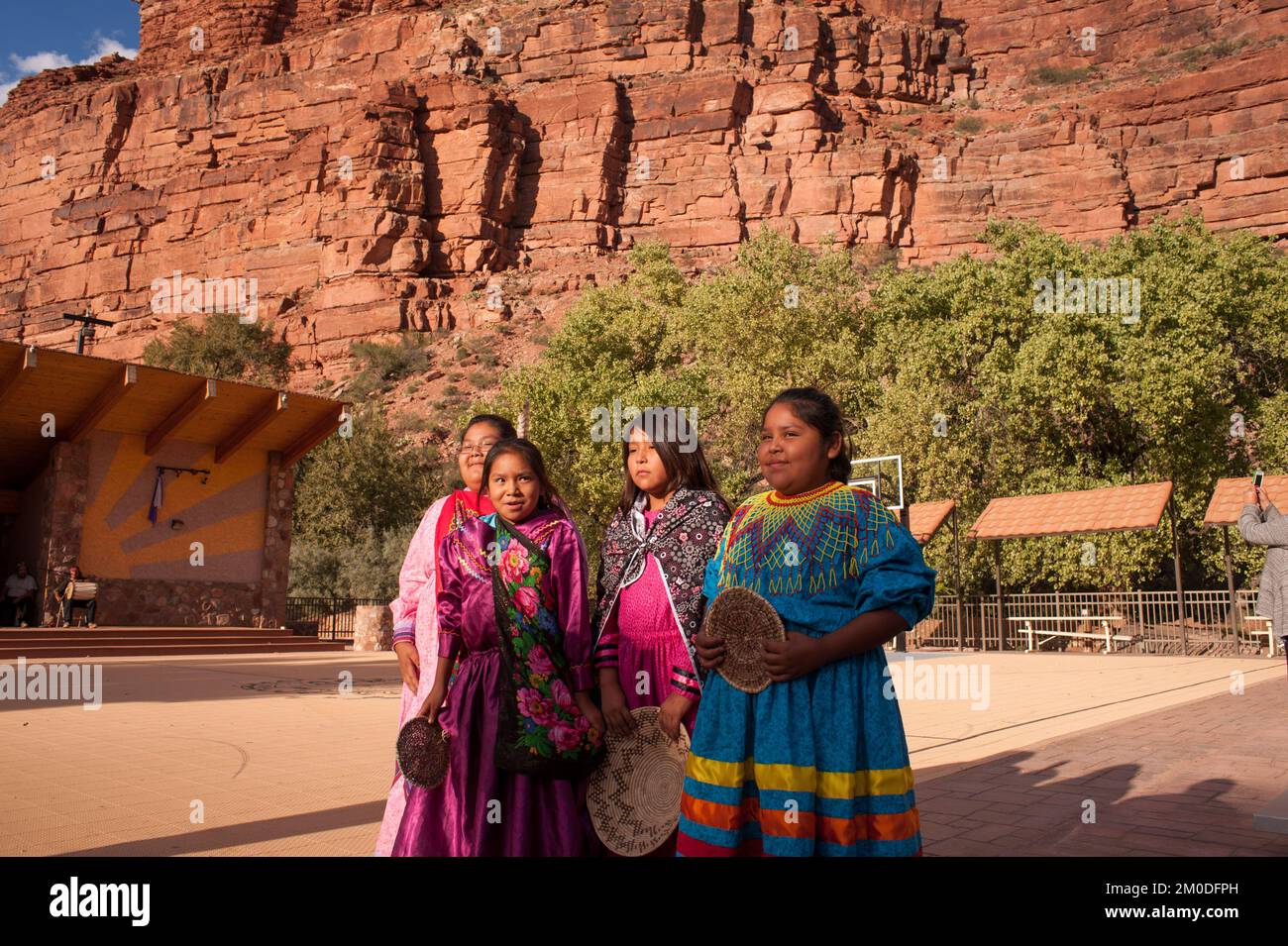

Yet, success brings its own set of challenges. Balancing the demands of a modern tourism industry with the preservation of ancient traditions is a delicate act. The tribe is committed to ensuring that its economic ventures serve to strengthen, rather than dilute, its cultural identity. Language immersion programs, traditional arts and crafts initiatives, and cultural education for younger generations are all critical components of their ongoing efforts.

Environmental stewardship is another paramount concern. As guardians of a segment of the Grand Canyon, the Hualapai Tribe is deeply committed to protecting its natural resources. They work to ensure that tourism development is sustainable and that the delicate ecosystem of the canyon is preserved for future generations. Their deep-rooted traditional ecological knowledge informs their approach to managing their lands and waters.

The Hualapai’s journey is far from over. They continue to assert their sovereignty, engage in legal battles to protect their rights and resources, and work towards a future where every tribal member has access to opportunities and a high quality of life. Their story is a powerful reminder that indigenous communities are not relics of the past but dynamic, resilient nations actively shaping their own futures.

From the ancient footpaths walked by their ancestors to the soaring glass bridge that now defines their modern enterprise, the Hualapai Tribe has navigated a path of profound change. They have transformed hardship into opportunity, demonstrating that true self-determination comes from within, rooted in culture, nurtured by community, and built with an unwavering vision for the future, all while standing proudly as the eternal guardians of the Grand Canyon. Their sky-high journey is a testament to the enduring spirit of a people who, against all odds, continue to thrive on the land they have always called home.