Desert Crossroads: The Yucca Arizona Bypass and a Thorny Path to Progress

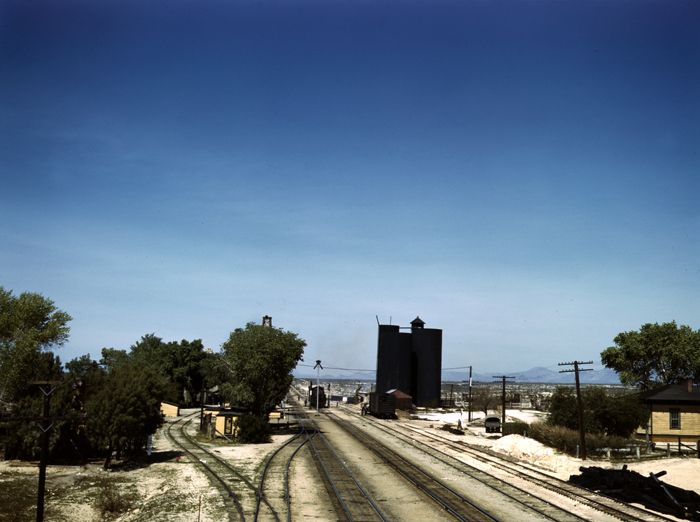

The Arizona desert, a landscape of stark beauty and resilient life, has long been a canvas for human ambition. From ancient trails to modern highways, the desire to connect distant points and facilitate commerce has shaped its contours. Today, one such endeavor, the proposed Yucca Arizona Bypass, stands as a potent symbol of this ongoing dynamic – a high-stakes infrastructure project promising economic uplift, yet threatening to carve a path through a fragile ecosystem and a landscape defined by its iconic, slow-growing sentinel: the yucca plant.

Stretching across an imagined swath of land near the existing U.S. Route 93 – the vital artery linking Phoenix to Las Vegas – the Yucca Arizona Bypass isn’t merely a line on a map. It represents a multi-billion-dollar investment, a promise of reduced travel times, increased safety, and a boost to the region’s burgeoning logistics and tourism industries. But for environmentalists, local residents, and the silent, spiky denizens of the desert, it also embodies a profound question: what is the true cost of progress?

The Rationale: A Ribbon of Asphalt for Prosperity

The genesis of the Yucca Arizona Bypass lies in the relentless growth of the American Southwest. U.S. 93, particularly the stretch passing through the Hualapai Valley and towns like Wikieup and the unincorporated community of Yucca itself, has become a choke point. Its two-lane configuration, winding through residential areas and commercial hubs, is ill-suited for the ever-increasing volume of commuter, commercial, and tourist traffic.

"The current Route 93 is a bottleneck, plain and simple," states Maria Rodriguez, a spokesperson for the Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT). "Every day, thousands of vehicles, from 18-wheelers carrying goods to families heading to the Grand Canyon, navigate a road that was never designed for this capacity. The bypass isn’t just about speed; it’s about safety, efficiency, and unlocking the economic potential of Western Arizona."

Proponents paint a vivid picture of the future: a four-lane, limited-access highway that bypasses existing communities, drastically cutting travel times, reducing accident rates, and creating new opportunities for development. Local businesses, particularly those involved in transportation and logistics, eagerly anticipate the improved flow of goods. "For years, we’ve seen our drivers stuck in traffic, burning fuel, losing time," says John Miller, owner of a trucking company based in Kingman. "This bypass will streamline our operations, make us more competitive, and bring jobs to an area that desperately needs them."

The economic impact assessment commissioned by ADOT projects thousands of temporary construction jobs, hundreds of permanent positions in new service industries, and an estimated increase of over $500 million annually in regional economic output within the first decade of the bypass’s operation. This is a powerful siren song for a region eager to diversify beyond its traditional mining and agricultural roots.

The Desert’s Silent Sentinels: The Yucca Challenge

However, the path to progress is not without its thorns, quite literally. The proposed bypass route traverses pristine Sonoran and Mojave desert landscapes, home to a diverse array of flora and fauna, chief among them the iconic yucca plant. Several species, including the striking Joshua Tree (Yucca brevifolia) and the graceful Soaptree Yucca (Yucca elata), are prevalent in the region. These plants, with their slow growth rates and deep taproots, are not merely decorative; they are foundational to the desert ecosystem.

"Yuccas are the silent sentinels of our desert," explains Dr. Elena Petrova, a botanist and co-founder of the ‘Save the Arizona Yucca’ coalition. "They provide shelter for countless species, from desert tortoises to nesting birds. Their root systems prevent soil erosion, and their unique symbiotic relationship with the yucca moth is a marvel of co-evolution. A single mature yucca can represent a century or more of growth. To simply clear-cut them is to erase generations of natural history."

The challenge of the bypass lies in mitigating the destruction of these plants. While some relocation efforts are planned, the success rate for transplanting large, mature yuccas is notoriously low. Their intricate root systems are easily damaged, and the shock of relocation often proves fatal. Even if a transplanted yucca survives, it can take decades for it to regain its ecological function, a mere fraction of its original lifespan.

"We are committed to minimizing environmental impact," counters ADOT’s Rodriguez. "Our plans include extensive environmental impact studies, a dedicated team of botanists for plant salvage and relocation, and the creation of mitigation sites where transplanted yuccas will be monitored. We’re also exploring innovative engineering solutions to reduce the footprint of the highway where possible."

A History of Relocation and Resistance

The Yucca Arizona Bypass isn’t the first time infrastructure development has clashed with the desert’s botanical heritage. In California, similar bypass projects through Joshua Tree forests have seen mixed results with relocation efforts, often highlighting the immense cost and limited success of such endeavors. A study on Joshua Tree transplantation for a solar farm project in California, for instance, reported survival rates as low as 30-50% for mature specimens, even with best practices. The cost per transplanted tree could run into thousands of dollars, making it a significant line item in project budgets.

For activists like Sarah Jenkins, a local resident and an ardent member of the ‘Save the Arizona Yucca’ coalition, these statistics are grim. "They talk about ‘mitigation,’ but often that’s just a fancy word for ‘managed destruction’," Jenkins asserts. "These aren’t just plants; they’re part of our heritage, our identity. My grandparents remembered these yuccas. What will my grandchildren see? Just another concrete jungle?"

The debate is further complicated by the area’s significance to Native American tribes, particularly the Hualapai and Mohave. Many desert plants, including various yucca species, hold cultural and medicinal importance. While ADOT has engaged in consultations, concerns remain about the impact on traditional lands and cultural resources. "Our ancestral lands are sacred," stated a representative from the Hualapai Nation during a public hearing. "These plants are not just ‘resources’ to be moved; they are our relatives, our teachers. Any development must respect this deep connection."

Engineering Solutions and Environmental Trade-offs

Beyond the yucca, the bypass project faces other environmental hurdles. The route may cross washes and ephemeral streams, critical for desert hydrology and wildlife movement. Desert tortoises, protected under the Endangered Species Act, inhabit the region, requiring careful surveys and potential habitat relocation. Dust generated during construction poses air quality challenges, and the long-term impact of increased vehicle emissions on air quality in a relatively pristine area is also a concern.

To address these, ADOT plans for wildlife underpasses, specialized fencing to guide animals away from the highway, and strict dust control measures. Advanced mapping technologies and environmental consultants are employed to identify sensitive areas and design the least impactful alignment. Yet, even with the most sophisticated engineering and environmental planning, some degree of irreversible impact is inevitable.

"It’s always a balancing act," admits Dr. Kenji Tanaka, an environmental engineer consulting on the project. "We strive for net-positive environmental outcomes where possible, but with large-scale infrastructure, there are always trade-offs. Our goal is to minimize the negative, maximize the positive, and ensure long-term sustainability through careful design and ongoing monitoring."

The Road Ahead: A Thorny Future?

As the Yucca Arizona Bypass moves from concept to concrete plans, the debate intensifies. Public hearings are often impassioned, with calls for alternative routes, greater investment in public transportation, or even a complete rethinking of the region’s development trajectory. Local businesses, eager for growth, clash with environmentalists and residents determined to protect their cherished landscape.

The bypass, if built, will undoubtedly reshape the Western Arizona corridor. It will bring faster travel and economic opportunity, but it will also permanently alter a unique and irreplaceable desert ecosystem. The success of its environmental mitigation efforts – particularly the fate of the relocated yuccas – will be closely watched, serving as a critical case study for future infrastructure projects in fragile desert environments.

The Yucca Arizona Bypass, therefore, is more than just a road. It is a microcosm of a larger, global dilemma: how do societies balance the undeniable pressures of economic growth and modernization with the imperative to preserve our natural heritage? As the desert sun beats down on the proposed route, the silent yuccas stand as stark reminders that the path to progress, while seemingly clear, can often be a thorny one, demanding difficult choices and an unwavering commitment to the planet we call home. The future of this corner of Arizona, and perhaps the very spirit of the desert, hangs in the balance.