Kearny County: Where the Prairie Whispers Tales of the Santa Fe Trail

The vast, unbroken expanse of the Kansas prairie, stretching endlessly under an immense sky, holds more than just fertile farmland and the rhythmic hum of modern agriculture. For those who know where to look, and listen, this land whispers tales of a bygone era, of adventure, hardship, and the relentless march of westward expansion. At the heart of these whispers, specifically within the boundaries of Kearny County, lies a crucial chapter in the story of the Santa Fe Trail – America’s first international highway, a lifeline that forged connections between nations and shaped the destiny of a continent.

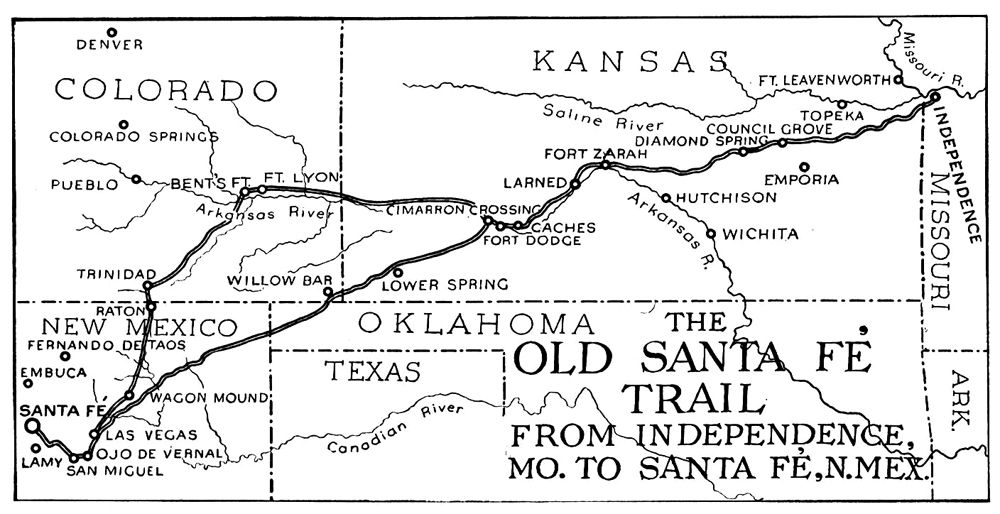

From 1821 to 1880, the Santa Fe Trail served as a vital commercial and military route, linking Franklin, Missouri, with Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was a rugged, nearly 900-mile journey that saw countless wagons laden with goods, military detachments, and hopeful pioneers brave the elements, treacherous terrain, and often hostile encounters. While the trail traversed multiple states, Kearny County, located in the southwestern quadrant of Kansas, played an outsized and often unforgiving role in this grand narrative. Its flat, seemingly innocuous landscape concealed some of the trail’s most challenging and pivotal segments, forcing traders and travelers to make critical decisions that often spelled the difference between success and disaster.

The Geographic Crucible: A Crossroads of Destiny

Kearny County’s significance on the Santa Fe Trail is inextricably linked to its geography, particularly its relationship with the Arkansas River. This major waterway formed a natural boundary for much of the trail’s central section. For travelers heading west, the Arkansas River presented a choice: continue along the relatively well-watered but longer "Wet Route" that hugged the river’s north bank, or dare to venture south across the river onto the notorious "Cimarron Cutoff."

The Cimarron Cutoff, while significantly shorter – shaving off about 100 miles – was infinitely more perilous. It plunged travelers into a desolate, arid landscape, often bereft of water for stretches exceeding 60 miles, a journey known as the "Jornada del Muerto" or "Journey of the Dead Man" in the minds of many. This challenging decision point, where the Wet Route continued west and the Cimarron Cutoff veered southwest, lay squarely within what is now Kearny County.

"The Arkansas River crossing was not merely a geographical transition; it was a psychological threshold," notes Dr. Eleanor Vance, a historian specializing in American frontier expansion. "Once you committed to the Cimarron, you were betting everything on your navigation skills, your animals’ endurance, and sheer luck to find water. Kearny County was where many of these life-or-death wagers were placed."

Wagon Bed Spring: A Lifeline in the Arid Expanse

Perhaps the most famous and vital landmark within Kearny County along the Cimarron Cutoff was Wagon Bed Spring, sometimes referred to as the Lower Spring. After enduring the excruciatingly dry stretch from the Arkansas River, this spring was often the first reliable water source travelers encountered. Its discovery was met with desperate relief, a literal oasis in the vast, unforgiving high plains. The name itself is steeped in lore, said to have come from an incident where a broken wagon bed was used to shore up the spring, improving its flow.

Imagine the scene: a weary wagon train, dust-caked and parched, animals faltering, human spirits flagging. Then, the cry of "Water!" and the sight of Wagon Bed Spring. It was here that many paused, rested, and replenished before continuing their arduous journey. The spring was not just a watering hole; it was a symbol of hope, a testament to the resilience of those who traversed the trail. Today, the site of Wagon Bed Spring is preserved, offering a tangible link to this crucial historical point, a place where one can almost hear the sighs of relief from travelers long past.

Another significant feature in Kearny County was the Point of Rocks, a distinctive bluff that served as a critical landmark for navigation, especially for those attempting to find Wagon Bed Spring or follow the Cimarron Cutoff. In an era before GPS and detailed maps, such natural features were indispensable guides across the featureless prairie. It was also a vantage point, offering a lookout for both approaching friends and potential dangers.

Life on the Trail: A Crucible of Endurance

Life on the Santa Fe Trail was a relentless test of endurance, skill, and sheer will. Wagon trains, often comprising dozens of "prairie schooners" drawn by teams of oxen or mules, moved at a snail’s pace, typically 10 to 15 miles a day. The journey was fraught with challenges: scorching summer heat, sudden violent thunderstorms, biting winter blizzards, and the constant threat of disease like cholera, which could decimate a party overnight. Accidents were common, with broken axles, runaway teams, and drownings during river crossings being ever-present dangers.

Beyond the natural elements, interactions with Native American tribes were a constant consideration. While trade and peaceful encounters certainly occurred, particularly with tribes like the Comanche and Kiowa, there were also periods of conflict. The trail, after all, cut through ancestral hunting grounds and disrupted traditional ways of life. Travelers often formed armed escorts, and vigilance was a constant companion, especially in the more isolated stretches of Kearny County.

"Every day was a gamble," wrote Josiah Gregg, a renowned Santa Fe trader whose 1844 book "Commerce of the Prairies" remains a seminal account of the trail. "The elements, the Indians, the very ground beneath your feet seemed bent on proving your mettle. And nowhere was this more true than in the dry stretches of the Cimarron." His vivid descriptions echo the hardships faced by countless others who traversed Kearny County.

The goods transported along the trail were diverse, reflecting the demands of both the American and Mexican markets. Westbound wagons carried manufactured goods – textiles, hardware, tools, and household items – desperately needed in the isolated communities of New Mexico. Eastbound, the wagons returned with Mexican silver coins, furs, wool, and mules, fueling the burgeoning American economy. Kearny County, sitting in the middle, witnessed this immense flow of commerce, a silent conduit for international trade.

The End of an Era: The Iron Horse Arrives

The golden age of the Santa Fe Trail, like many other great overland routes, eventually succumbed to the relentless march of technological progress. The advent of the railroad proved to be its ultimate undoing. As the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway pushed westward, it gradually absorbed the trail’s freight business. By 1872, the railroad reached Lakin, the future county seat of Kearny County, effectively rendering the laborious wagon journey through the county obsolete for commercial purposes.

The final spike of the Santa Fe Railroad into Santa Fe itself in 1880 marked the official end of the trail’s commercial era. The rumble of wagon wheels gave way to the shriek of steam whistles, and the dusty tracks of the trail slowly began to fade back into the prairie.

Legacy and Modern Echoes

Despite its physical disappearance, the legacy of the Santa Fe Trail, and Kearny County’s place within it, endures. The trail is now recognized as a National Historic Trail, with efforts underway to preserve its remaining ruts, archaeological sites, and the stories they tell. In Kearny County, one can still find faint swales – the ghost ruts – etched into the landscape, visible reminders of the thousands of wagons that once passed this way. Interpretive signs mark significant points, inviting visitors to step back in time and imagine the lives of those who forged this path.

The spirit of resilience, innovation, and perseverance that characterized the Santa Fe Trail travelers undoubtedly helped shape the character of Kearny County. The early settlers who arrived in the wake of the trail’s commercial decline inherited a landscape imbued with the history of struggle and triumph. They transformed the once-wild prairie, watered by the same Arkansas River that challenged the traders, into a productive agricultural heartland, continuing the tradition of adapting and thriving in a challenging environment.

Kearny County today stands as a quiet testament to a pivotal chapter in American history. It is a place where the vastness of the prairie still allows for reflection, where the echoes of wagon wheels and the cries for water at Wagon Bed Spring can still be heard by those who take the time to listen. The Santa Fe Trail through Kearny County is more than just a historical route; it is a symbol of human ambition, a reminder of the challenges overcome, and an enduring monument to the spirit of exploration that helped define a nation. To visit is to connect with the raw, untamed essence of the American West, where the past is not merely remembered, but vividly felt in the whispering winds of the Kansas prairie.