John C.H. Grabill: The Silent Lens That Chronicled the Vanishing American Frontier

In the vast, sprawling narrative of the American West, few figures cast as long a shadow with such an enigmatic presence as John C.H. Grabill. His name may not echo with the same recognition as a Frederic Remington or a Charles M. Russell, yet his photographs—stark, unvarnished, and profoundly evocative—form an indispensable visual lexicon of a frontier on the cusp of profound change. From the bustling, often lawless boomtowns of the Black Hills to the solemn, snow-dusted aftermath of Wounded Knee, Grabill’s lens captured a world teetering between myth and modernity, creating an enduring legacy that continues to shape our understanding of this pivotal era.

Grabill was not merely a photographer; he was a meticulous documentarian, a visual historian who, perhaps unwittingly, froze moments in time that would otherwise have been lost to the relentless march of progress. Active primarily between 1887 and 1892, his work spanned a crucial five-year period when the last vestiges of the untamed West were giving way to settlement, industry, and federal control. His images are more than just pretty pictures; they are primary sources, offering an intimate, often unsettling, glimpse into the lives of cowboys, miners, Native Americans, and the landscapes they inhabited.

Born in Ohio in 1860, John C.H. Grabill’s early life remains largely obscure, a characteristic that would define much of his existence. What is known is that he arrived in the Dakota Territory in the late 1880s, drawn by the promise and chaos of the Black Hills Gold Rush. He established his "Grabill, Photographer" studios in several key locations, including Deadwood, Sturgis, Lead, and Hot Springs, towns that were then vibrant hubs of mining activity, commerce, and the rough-and-tumble frontier spirit. He later expanded his operations to Chicago and Cheyenne, Wyoming, but it was his time in the Dakotas that yielded his most historically significant work.

His photographic output was prodigious and remarkably diverse. Grabill’s portfolio serves as a veritable visual encyclopedia of late 19th-century frontier life. He meticulously documented the burgeoning towns, with their wooden storefronts, muddy streets, and throngs of hopeful prospectors and entrepreneurs. His images show the intricate operations of gold mines, with their towering hoists and shafts delving deep into the earth, illustrating the brutal reality of resource extraction that fueled the region’s economy. He captured cowboys, not as romanticized figures of fiction, but as working men, herding cattle, branding, and enduring the harsh realities of the range.

Beyond the industry and settlement, Grabill had a profound interest in the natural grandeur of the West. His landscape photographs showcase the rugged beauty of the Black Hills, the vastness of the plains, and the dramatic geological formations that defined the region. These images, often taken with cumbersome, large-format glass plate cameras, required not only artistic vision but also immense physical effort and technical skill. The process involved heavy equipment, dangerous chemicals, and the need for portable darkrooms in often remote and challenging environments, making Grabill’s dedication all the more remarkable.

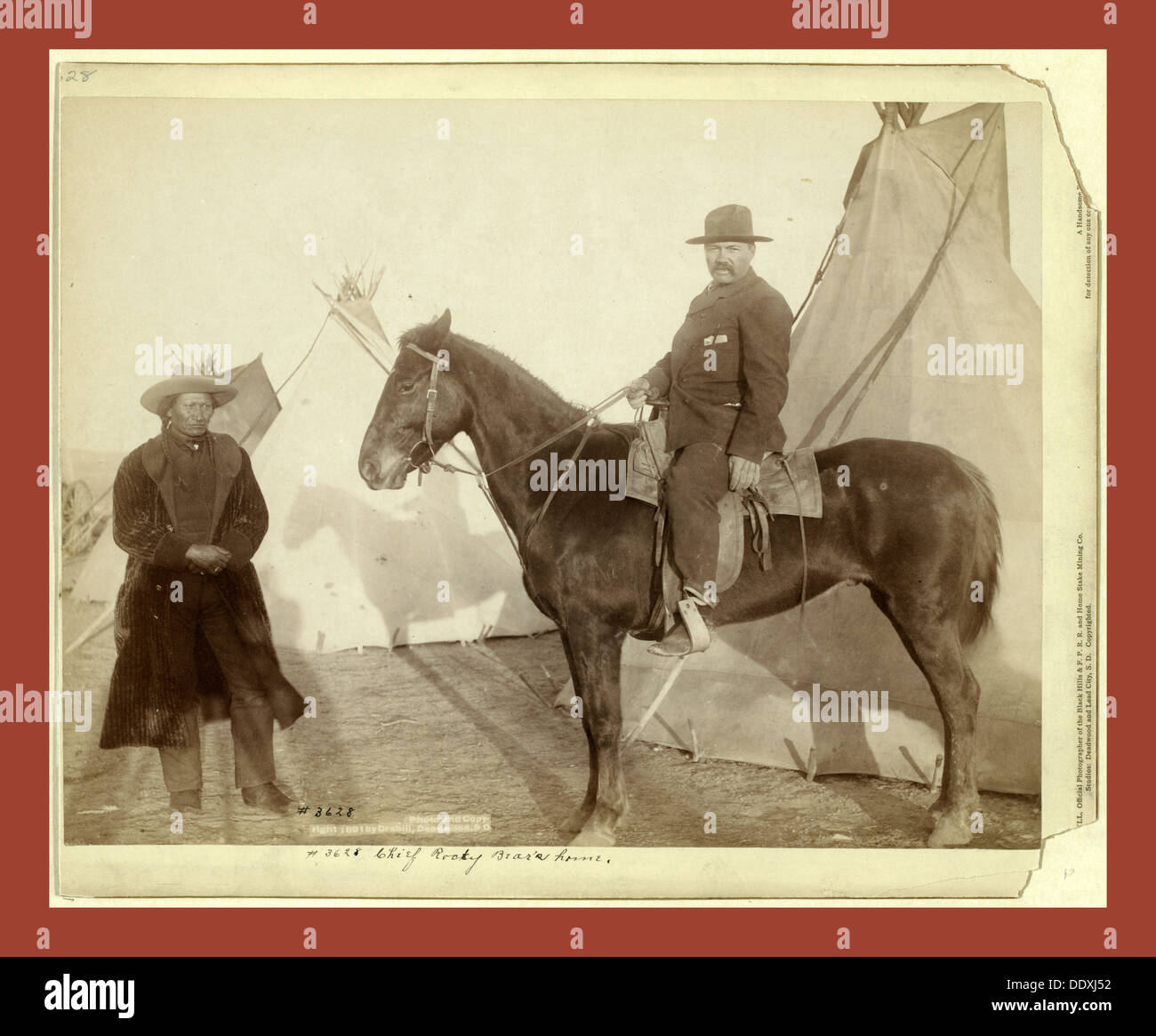

However, it is Grabill’s extensive documentation of the Native American peoples of the Northern Plains, particularly the Lakota Sioux, that stands as his most compelling and complex contribution. At a time when federal policy was aggressively aimed at assimilation and the eradication of Indigenous cultures, Grabill captured images of Lakota individuals and communities with a dignity and directness that was rare for the period. His photographs depict tribal leaders, families, and encampments, often posed but never entirely devoid of the resilience and spirit of a people facing immense pressure.

These images are particularly poignant when viewed through the lens of the impending tragedy. Grabill was working during the height of the Ghost Dance movement, a spiritual revival that promised a return to traditional ways and the expulsion of white settlers, bringing hope to a desperate people but also inciting fear and aggression among the U.S. military. His photographs from this period, taken just before and after the Wounded Knee Massacre, offer an unparalleled, albeit often unsettling, record of the tension and ultimately, the devastation that unfolded.

The defining moment of Grabill’s career, and arguably one of the most significant photographic documentations in American history, came in the wake of the Wounded Knee Massacre. On December 29, 1890, near Wounded Knee Creek on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, U.S. 7th Cavalry troops massacred approximately 300 Lakota men, women, and children. Grabill arrived on the scene shortly after, capturing the horrific aftermath. His photographs of the frozen bodies of the Lakota dead, scattered across the snow-covered ground, are among the most powerful and disturbing images ever taken of American history.

These photographs served as immediate, irrefutable evidence of the brutality of the massacre. They were widely circulated, shaping public perception and fueling debate about U.S. Indian policy. While some viewed them as sensationalism or justification for military action, others saw them as a damning indictment. Regardless of the contemporary interpretation, Grabill’s images from Wounded Knee remain an essential, visceral record of a dark chapter, serving as a stark reminder of the human cost of conquest and conflict. They transformed abstract historical events into tangible, undeniable visual facts, ensuring that the tragedy would not be easily forgotten.

After Wounded Knee, Grabill’s output diminished. He eventually moved to Chicago, where he continued to work as a photographer, though his later life lacks the dramatic historical context of his Dakota years. Details of his later years are scarce, and his eventual death date and location are largely unknown, adding to the mystique surrounding the man behind the lens. It’s as if, having documented the end of an era, Grabill himself faded into the background, allowing his images to speak for themselves.

The survival and preservation of Grabill’s work are a testament to its intrinsic historical value. A substantial collection of his glass plate negatives, over 1,200 images, were acquired by the Library of Congress, where they now form a crucial part of the national photographic archives. This collection ensures that his visual legacy endures, providing researchers, historians, and the public with an invaluable window into a bygone era. These fragile plates, once painstakingly exposed and processed in makeshift frontier darkrooms, are now digitalized, allowing their stories to reach a global audience.

John C.H. Grabill’s contribution extends beyond mere historical documentation. His photographs possess an artistic quality, a compositional strength, and an emotional depth that elevate them to more than just records. They evoke a sense of the vastness and wildness of the frontier, the resilience of its inhabitants, and the profound changes taking place. His work captures the light, the texture, and the very atmosphere of the late 19th-century West, making the distant past feel remarkably present.

In conclusion, John C.H. Grabill remains one of the most significant, yet often unsung, visual chroniclers of the American Frontier. His lens did not merely record; it interpreted, it bore witness, and it preserved. From the daily grind of the gold rush towns to the ultimate tragedy of Wounded Knee, Grabill’s photographs offer an unparalleled, unflinching look at a pivotal moment in American history. He was a phantom behind the camera, his personal story largely lost to time, but his visual legacy endures—a powerful, poignant, and indispensable testament to the vanishing West and the complex, often brutal, forces that shaped it. His images compel us to look, to remember, and to understand, ensuring that the echoes of the frontier continue to resonate through the silent power of his gaze.