.jpg?mode=max)

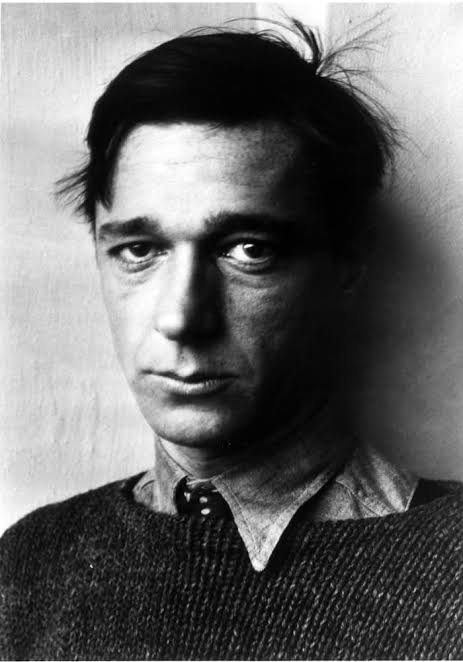

The Unblinking Eye: Walker Evans and the Enduring American Truth

In the vast, often subjective landscape of photography, few figures stand as resolute and foundational as Walker Evans. His name is synonymous with an unwavering commitment to objective truth, a photographic style so starkly honest it became an art form in itself. Born in 1903, Evans did not just document America; he meticulously, almost clinically, cataloged its essence – its vernacular architecture, its forgotten faces, its everyday objects – with an unblinking eye that revealed both the grandeur and the grit of a nation in flux. His legacy, most famously forged during the Great Depression, transcends mere historical record, offering a profound, timeless meditation on identity, authenticity, and the very act of seeing.

To understand Evans’s impact, one must first grasp the context of his most celebrated work: his tenure with the Farm Security Administration (FSA) from 1935 to 1938. As America grappled with the devastating economic collapse of the Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal initiatives sought to alleviate suffering and rebuild the nation. The FSA, under the visionary leadership of Roy Stryker, understood the power of images to convey the human cost of the crisis and to garner public support for relief efforts. Stryker assembled a team of photographers, including Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and Russell Lee, to visually document rural poverty. Evans, with his sophisticated aesthetic and quiet intensity, was a crucial, if sometimes challenging, addition to this roster.

Evans’s approach immediately set him apart. While other FSA photographers often aimed for emotive, sometimes even propagandistic, images to elicit sympathy, Evans pursued a different path. He sought an "objective document," a photographic equivalent of what he admired in literature: the precise, unadorned prose of Flaubert or the detached observations of Baudelaire. He abhorred sentimentality, grand gestures, or any visual trickery. His camera, typically a large-format 8×10 view camera, was not an instrument of manipulation but a tool of dispassionate observation. He meticulously composed his shots, ensuring sharp focus and a balanced frame, presenting the world as it was, allowing the stark reality to speak for itself.

This "straight photography" approach is perhaps best exemplified in his collaboration with writer James Agee, which culminated in the seminal 1941 book, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Tasked by Fortune magazine in 1936 to document the lives of sharecropper families in the American South, Evans and Agee immersed themselves in the abject poverty of Hale County, Alabama. Agee’s lyrical, often anguished prose described the ineffable suffering, while Evans’s photographs provided the stark, unvarnished visual evidence. His portraits of the Gudger, Woods, and Burroughs families are not caricatures of destitution but dignified, almost monumental, studies of resilience. Faces etched with hardship gaze directly at the viewer, their eyes holding stories that Agee’s words only began to articulate. The interiors of their meager homes, the worn tools, the threadbare clothing – every detail is rendered with an almost archaeological precision, transforming the mundane into profound statements of human endurance.

"The good photographer," Evans once stated, "is one who sees the picture better than it is printed." This philosophy underscores his belief that the act of seeing, the initial conceptualization, was paramount. He saw beauty not in the conventionally picturesque, but in the forgotten, the functional, the unadorned. His lens found poetry in dilapidated storefronts, roadside signs, barber shop interiors, and the anonymous faces of passersby. He was, in essence, an archivist of the American vernacular, documenting the visual language of a nation before it was irrevocably altered by progress and homogenization.

Evans’s work with the FSA culminated in a groundbreaking exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1938, titled American Photographs. This was a pivotal moment, cementing photography’s status as a serious art form and establishing Evans as a leading voice. The exhibition, and the accompanying book, showcased his diverse range, moving beyond the sharecropper images to include his studies of small-town architecture, public buildings, and the detritus of everyday life. It was a comprehensive visual inventory of America, presented without commentary, inviting viewers to draw their own conclusions.

But Evans’s photographic vision extended far beyond the Depression era. After leaving the FSA, he continued to push boundaries. One of his most fascinating and audacious projects was his "Subway Series" (1938-1941), where he secretly photographed commuters on the New York City subway using a hidden camera. These candid portraits, taken without the subjects’ knowledge or consent, offer an intimate, unguarded glimpse into the faces of urban America – tired, reflective, lost in thought. They are a testament to his relentless curiosity about the human condition and his desire to capture unposed, authentic moments. He saw these anonymous faces as archetypes, reflections of a collective urban experience. "The secret photography," he explained, "was an exercise in pure observation, an attempt to strip away pretense and capture the unguarded self."

From 1945 to 1965, Evans worked as a staff photographer for Fortune magazine, a seemingly incongruous role for an artist so committed to stark reality. Yet, he adapted his rigorous aesthetic to the demands of corporate journalism, finding opportunities to explore industrial landscapes, the interiors of corporate offices, and the details of modern manufacturing with the same meticulous eye he applied to rural poverty. He demonstrated that his "documentary style" was not confined to a specific subject matter but was a transferable methodology for seeing and recording. Even in the glossy pages of Fortune, Evans managed to inject his characteristic blend of dispassionate observation and subtle critique, often highlighting the contrast between the pristine surfaces of modernity and the underlying human effort.

In his later years, Evans taught photography at Yale University, influencing a new generation of artists. He continued to photograph until his death in 1975, often focusing on color photography, a medium he initially approached with skepticism but ultimately embraced, applying his signature precision to its vibrant palette. His enduring legacy lies not just in the iconic images he produced, but in the profound shift he brought to photographic practice. He championed the idea that photography’s strength lay in its ability to be a factual record, rather than a painterly interpretation.

Evans’s influence on subsequent generations of photographers is immeasurable. Artists like Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus, and Stephen Shore, among countless others, owe a debt to his pioneering spirit. He taught them that the most compelling narratives often lie in the ordinary, the overlooked, and the unadorned. His insistence on clarity, directness, and an almost clinical objectivity became a cornerstone of modern documentary and street photography. He proved that a photograph could be both a truthful document and a profound work of art, without needing to be embellished or manipulated.

Ultimately, Walker Evans’s work is a timeless quest for truth. He was not interested in telling people what to feel, but in showing them what was there, allowing them the space to interpret, to connect, to understand. His photographs are not just windows into a specific historical moment; they are mirrors reflecting the enduring complexities of American identity – its resilience, its disparities, its unique visual language. In an age saturated with manipulated images and fleeting digital impressions, Evans’s unwavering commitment to the "straight" photograph, to the unblinking eye, remains a powerful and necessary reminder of the profound honesty that a camera, in the hands of a master, can achieve. He captured the American truth, and in doing so, he helped us see ourselves anew.