The Quiet Chronicler: Russell Lee’s Enduring Lens on the American Soul

The Great Depression cast a long, dark shadow across the American landscape, etching itself into the national consciousness through stark, unforgettable images. While Dorothea Lange’s "Migrant Mother" remains an iconic symbol of suffering, and Walker Evans’s austere portraits defined an era of stark poverty, another photographer worked with quiet intensity, compiling a vast, empathetic, and ultimately optimistic record of the nation’s resilience. Russell Lee, often overshadowed by his more celebrated contemporaries, was arguably the most prolific and comprehensive visual chronicler of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) project, meticulously documenting the daily lives, struggles, and enduring spirit of ordinary Americans.

Born in Ottawa, Illinois, in 1903, Russell Werner Lee initially pursued a path far removed from photography. He studied chemical engineering at Lehigh University, a pragmatic choice that hinted at a methodical mind, but one that soon found itself yearning for artistic expression. After a brief stint in industry, Lee turned to painting, enrolling at the California School of Fine Arts. It was during this period, however, that he stumbled upon the camera, quickly realizing its immense potential not just for artistic composition, but for social commentary. In the nascent documentary photography movement, Lee saw a powerful tool to engage with the world, to bear witness, and to advocate for change. The onset of the Great Depression deepened this conviction, pushing him towards a more direct and unvarnished approach to art.

In 1936, this burgeoning passion led him to join the historical section of the Farm Security Administration, an ambitious government initiative led by the visionary Roy Stryker. Stryker’s mission was clear: to document the devastating impact of the Depression on rural America and to build public support for the New Deal programs designed to alleviate the crisis. He assembled a dream team of photographers, including Lange, Evans, Arthur Rothstein, and Gordon Parks, but it was Lee who would contribute the largest volume of work, producing an astonishing collection of over 19,000 negatives for the FSA archive.

Lee’s approach was distinct, characterized by an understated empathy and an almost anthropological rigor. Unlike some of his peers who sought out dramatic, often symbolic compositions of suffering, Lee was drawn to the rhythms of everyday life. He immersed himself in communities, spending weeks, sometimes months, in small towns and rural settlements across the Midwest, South, and Southwest. His camera was not an intrusive weapon, but a tool of gentle inquiry. He developed a remarkable ability to blend into his surroundings, earning the trust of his subjects, allowing them to reveal themselves naturally and with dignity. Roy Stryker himself recognized this unique quality, noting, "Lee could go into a town and become a part of it in a day or two… He never intruded."

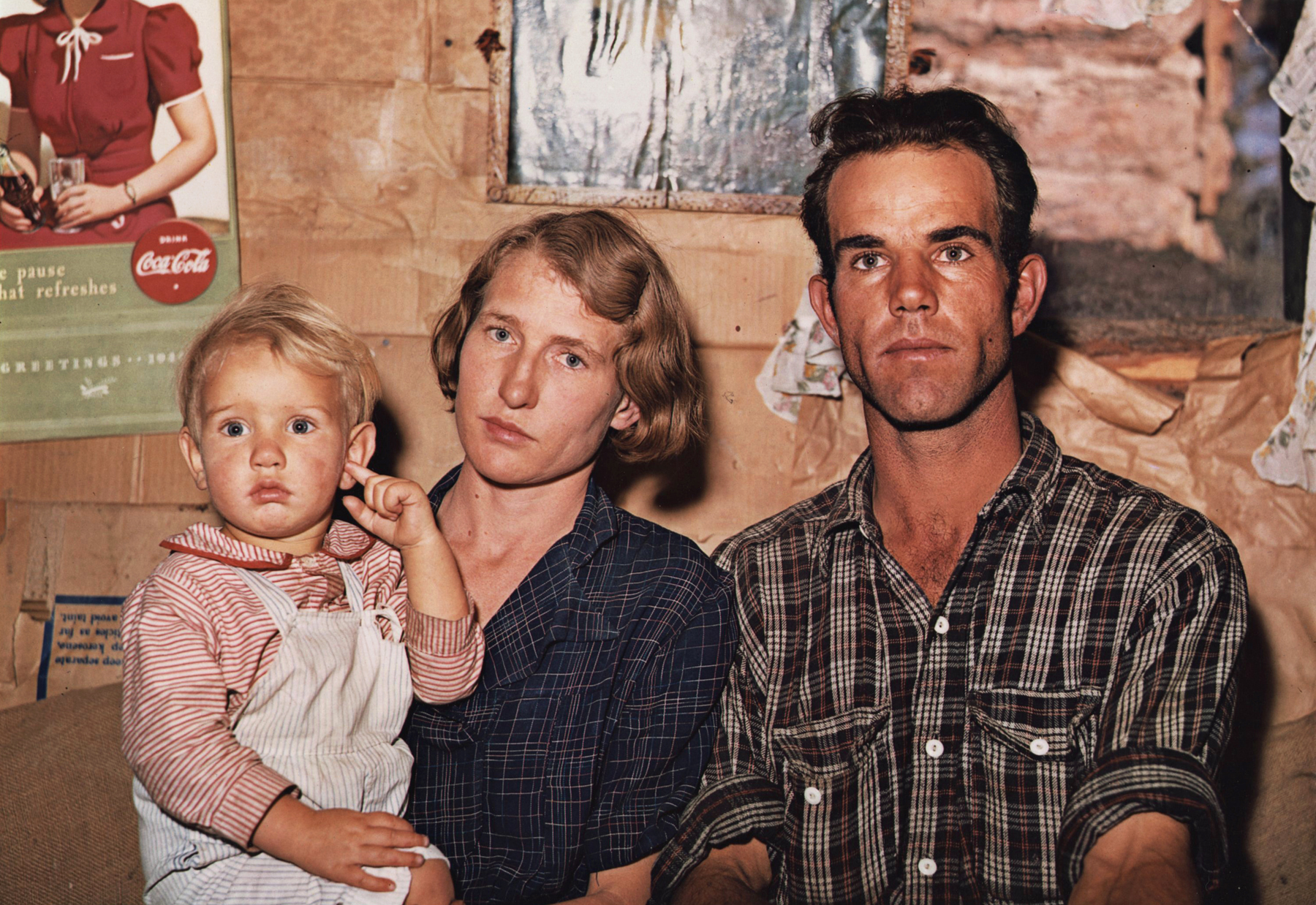

This non-intrusive style allowed Lee to capture moments of profound authenticity. His photographs seldom depict overt anguish; instead, they show the quiet endurance, the resourcefulness, and the unwavering sense of community that defined many lives during this trying period. From the parched fields of the Dust Bowl to the cramped quarters of migrant camps, from the bustling general stores of small towns to the intimate family dinners, Lee’s lens found dignity in the mundane, resilience in hardship, and beauty in the ordinary. He showed people not just as victims, but as active participants in their own survival, often displaying a fierce pride despite their circumstances.

One of his most celebrated bodies of work emerged from Pie Town, New Mexico, where he lived and photographed a community of homesteaders in 1940. Over several months, Lee meticulously documented every facet of their lives: farming, church services, school lessons, communal meals, and family gatherings. The resulting images are a masterclass in ethnographic photography, offering an unparalleled glimpse into a way of life that was both harsh and deeply rewarding. His portraits from Pie Town, like "Pie Town, New Mexico. Mrs. Willy Black holding the pie she has just made," are not just records of individuals, but windows into their character – strong, self-reliant, and imbued with an unyielding spirit. These photographs are imbued with a warmth and intimacy that speak volumes about Lee’s connection with his subjects, a testament to his patience and genuine respect.

Technically, Lee was also a quiet innovator. He was one of the first documentary photographers to extensively use flash photography, particularly indoors and in low-light conditions, long before it became commonplace. This allowed him to capture interior scenes with a clarity and depth that were revolutionary for the time, illuminating the textures of homes, the expressions on faces around a dinner table, and the details of everyday objects that would otherwise have been lost in shadow. His compositions were often straightforward, eschewing dramatic angles for a direct, honest presentation, yet they were always carefully considered, showcasing his painter’s eye for light, form, and narrative. Furthermore, Lee was meticulous in his record-keeping, providing detailed captions and contextual notes for virtually every photograph – a priceless gift to future historians and researchers.

Lee’s work wasn’t limited to black and white. In the early 1940s, as Kodachrome film became more accessible, Roy Stryker encouraged his photographers to experiment with color. Russell Lee embraced this challenge with characteristic thoroughness, producing some of the earliest and most significant color documentary photographs of the era. His color images, often depicting small-town life, storefronts, and vibrant community events, added another layer of richness to his already comprehensive visual record. They remind us that even during the darkest times, life was lived in full spectrum, not just shades of grey.

After the FSA project concluded in 1943, Lee continued his prolific career, applying his documentary skills to a variety of assignments. He photographed for the Air Transport Command during World War II, documenting military operations across the globe. Later, he embarked on a multi-year project for Standard Oil of New Jersey, capturing the vast, complex machinery and human endeavor behind the oil industry. These assignments, while different in subject matter, still bore the hallmarks of Lee’s approach: comprehensive coverage, a keen eye for human interaction with their environment, and a commitment to meticulous detail.

In 1965, Russell Lee settled in Austin, Texas, where he became a faculty member at the University of Texas, teaching photography and helping to establish its extensive photography archive. He continued to photograph, turning his lens on the evolving landscape of Texas and its people, always with the same quiet curiosity and profound respect. He dedicated his later years to organizing his vast personal archive, ensuring that his life’s work would be preserved and accessible.

Russell Lee passed away in 1986, leaving behind an unparalleled photographic legacy. His work, now housed in the Library of Congress and other major institutions, serves as an invaluable historical record of a pivotal period in American history. More than just images of hardship, his photographs are a testament to human resilience, dignity, and the enduring power of community. He showed us that even in the face of overwhelming adversity, people continued to live, to work, to love, and to find moments of joy and connection.

In an age often defined by sensationalism and fleeting images, Russell Lee’s quiet chronicling reminds us of the profound power of empathy and the enduring value of thorough, respectful documentation. He wasn’t chasing the single, dramatic shot, but building an expansive, nuanced narrative, one frame at a time. Through his lens, we don’t just see the Great Depression; we understand the spirit of the people who lived through it, making Russell Lee an essential, though perhaps still underappreciated, master of American photography. His gentle gaze continues to teach us about who we were, and who we can be, as a nation.