Awa Tsireh: The Brushstrokes of Tradition and Transformation at San Ildefonso

In the early decades of the 20th century, a vibrant artistic renaissance blossomed in the Pueblos of the American Southwest, forever changing how Native American art was perceived and collected. At the heart of this "Golden Age" of Pueblo painting stood Alfonso Roybal, better known by his Tewa name, Awa Tsireh, or "Pond Blossom." A masterful artist from San Ildefonso Pueblo, Awa Tsireh was not merely a painter; he was a cultural bridge-builder, an innovator who, with each meticulous brushstroke, navigated the complex currents between ancient traditions and the burgeoning demands of a modern, Western art market. His work, characterized by its exquisite detail, flat planes, and dynamic depiction of ceremonial life and natural forms, offered an unprecedented window into a world often misunderstood, cementing his legacy as one of the most influential Native American artists of his time.

Born in 1898, Awa Tsireh came of age during a period of immense change and cultural scrutiny for the Pueblo peoples. San Ildefonso, nestled against the stunning backdrop of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, was already a crucible of artistic innovation, renowned for its pottery. His aunt, the legendary Maria Martinez, along with her husband Julian, had perfected the iconic black-on-black pottery, bringing international acclaim to the pueblo. This environment of artistic excellence and cultural pride undoubtedly shaped young Alfonso. Unlike the potters, however, Awa Tsireh would choose a new canvas: paper, and a new medium: watercolor and tempera.

The emergence of Pueblo painting on paper was spurred by a confluence of factors, including the interest of ethnographers and anthropologists like Edgar Lee Hewett, director of the School of American Research (SAR) in Santa Fe, and Kenneth Chapman, an anthropologist and expert on Pueblo pottery design. These men, recognizing the innate artistic talent within the Pueblos, encouraged young artists to translate their traditional designs and ceremonial knowledge onto a new format. This encouragement, while well-intentioned, also presented a subtle tension: it was a call to create art that was "authentic" in the eyes of external observers, yet deeply rooted in the artists’ own cultural experience.

Awa Tsireh was among the first and most prolific of these early painters. Starting around 1917, he began to paint scenes of Pueblo life, ceremonial dances, and natural elements with an astonishing skill. His early works often depicted figures in motion, imbued with a sense of solemn grace and spiritual power. He was a natural draftsman, capable of rendering intricate details of traditional regalia, feathers, and ritual objects with remarkable precision. This attention to detail was not merely aesthetic; it was an act of cultural preservation, meticulously recording the visual lexicon of his people.

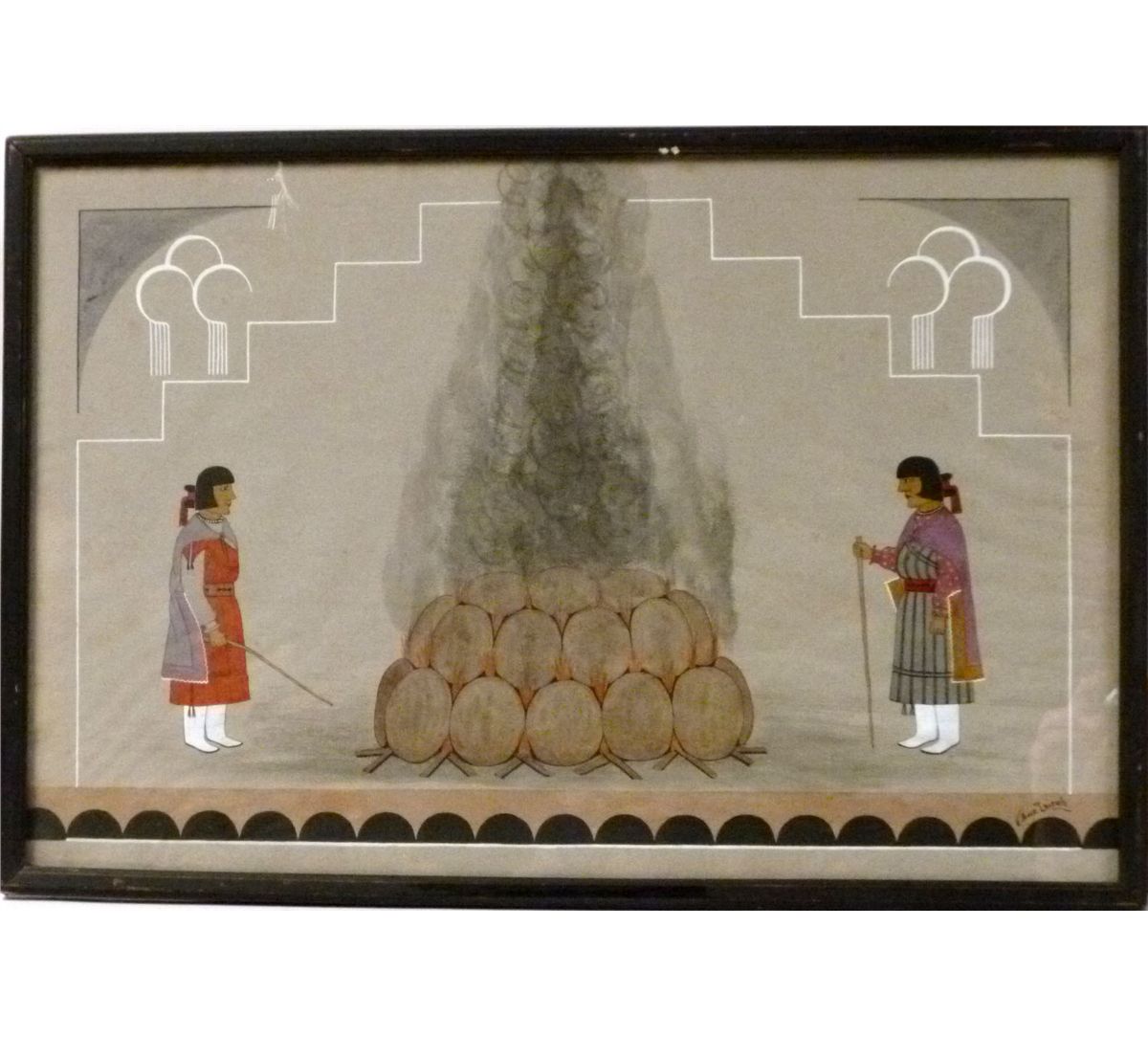

One of the most striking characteristics of Awa Tsireh’s style was his adherence to a non-Western artistic tradition. His paintings largely avoided the conventions of European art, such as linear perspective, chiaroscuro (light and shadow), or a defined horizon line. Instead, figures often appear in flat, two-dimensional planes, outlined with strong, clean lines. This approach, while initially perceived by some Western critics as "primitive," was, in fact, a sophisticated stylistic choice that emphasized the spiritual and symbolic over the strictly representational. It reflected a worldview where all elements – human, animal, and spiritual – existed on a single, interconnected plane of existence.

As his reputation grew, Awa Tsireh’s work became a cornerstone of the burgeoning Santa Fe art scene. He exhibited his paintings widely, gaining critical acclaim and a dedicated following among collectors and institutions. His art was featured in major exhibitions, including the Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts in New York in 1931, which brought Native American art to a national audience on an unprecedented scale. This exposure, however, also meant navigating the expectations of a market that often sought an idealized, "timeless" vision of Native American culture, sometimes at the expense of acknowledging its contemporary realities.

The establishment of the Studio School at the Santa Fe Indian School in 1932, under the guidance of Dorothy Dunn, further cemented the direction of Pueblo painting. Dunn, a passionate advocate for Native American art, developed a curriculum that encouraged students to paint "authentically" from their own cultural heritage, largely eschewing Western art techniques. While the school provided crucial support and training for a generation of artists, it also created a certain stylistic template, often favoring the flat, descriptive style exemplified by Awa Tsireh and his contemporaries. Dunn herself recognized Awa Tsireh’s foundational role, calling him "a major contributor to the foundation of the modern Indian art movement."

Awa Tsireh’s subjects were diverse, yet consistently rooted in his Pueblo identity. He painted ceremonial dancers such as the Eagle, Deer, and Buffalo dances, capturing the energy and spiritual significance of these rituals. He also depicted genre scenes of daily life: hunting, farming, and interactions with the natural world. His animal paintings, particularly his birds and deer, are renowned for their delicate beauty and symbolic resonance. These images were not merely illustrations; they were visual narratives, imbued with the deep spiritual meaning and cosmology of the Tewa people.

A Fascinating Fact: Awa Tsireh’s willingness to paint inside the Pueblo for an external audience was, at the time, revolutionary. Traditionally, many Pueblo ceremonies and their visual representations were considered sacred and not for public display or external interpretation. His work, therefore, walked a delicate line, sharing aspects of his culture while still respecting its deeper mysteries. He carefully selected which elements to depict, often focusing on the more public aspects of ceremonial life or using symbolism that could be appreciated without fully revealing esoteric knowledge. This strategic presentation allowed him to educate and captivate outsiders while maintaining the integrity of his cultural heritage.

The challenge for Awa Tsireh and his peers was to bridge two worlds: to create art that was deeply personal and culturally resonant for his own people, while simultaneously appealing to a non-Native audience that often viewed it through a lens of romanticism or exoticism. He managed this tightrope walk with grace and integrity. His art never felt compromised; it was always authentically his own, a powerful testament to the resilience and vibrancy of Pueblo culture.

Awa Tsireh’s influence extended far beyond his own prolific output. He inspired countless younger artists from San Ildefonso and other Pueblos, many of whom adopted and adapted his signature style. He was a mentor, a role model, and a living example of how one could embrace modern opportunities without sacrificing one’s cultural roots. His work helped to establish a new category of "Native American fine art," challenging the long-held notion that indigenous artistic expressions were merely ethnographic curiosities or craft.

In his later years, Awa Tsireh continued to paint, though his most celebrated period is often considered to be the 1920s and 30s. He remained a respected elder in his community, contributing to the cultural life of San Ildefonso. He passed away in 1955, leaving behind a vast and invaluable body of work that continues to be celebrated in major museums and collections worldwide.

Awa Tsireh’s legacy is multifaceted. He was a pioneer who helped to define a new artistic movement, a cultural ambassador who shared the beauty and depth of Pueblo life with the world, and an artist of profound skill and vision. His paintings are more than just beautiful images; they are historical documents, spiritual reflections, and powerful statements of cultural identity. In every stroke of his brush, Awa Tsireh revealed a world of tradition, transformed it through his unique artistic lens, and in doing so, ensured that the vibrant spirit of San Ildefonso Pueblo would resonate for generations to come. His "Pond Blossom" may have dried on the paper, but its colors and meaning continue to bloom in the annals of American art history.